The Origins of Racing at Epsom

Part One

Strangely, the events that led up to the foundation of the Derby started in the dry summer of 1618, when a humble herdsman, Henry Wicker, stumbled across a small hole full of water on the common, to the north-west of the turnpike road, between Epsom and Ashtead.

To Wicker’s amazement, after enlarging the hole in order to water his cattle, they refused to drink. And when he sampled it, neither would he. Some months later, samples of the water were examined by local physicians, who deemed it aluminous and recommended it for external use on cuts and sores. It was not until about 1830 that the highly purgative qualities of the water were discovered; this quite by chance, when a group of labourers drank deeply from the spring.

Epsom’s old wells

While at first knowledge of the waters remained local, word soon travelled to wealthy Londoners, whose appreciation of the remedy eventually brought patronage from the nobility of England, with Epsom then rivalling Tunbridge Wells for its famed cures.

John Toland, the famous religious writer noted, “Since it hath been inwardly taken, diseases have met with their cure, though they proceed from contrary causes.” He also observed that citizens of London arriving “from the worst of smokes to the best of airs”, quickly found themselves restored to perfect health. Very soon, the waters were amongst the most analysed substances in England (one gallon of water containing 480 grains of calcareous nitre), with entrepreneurs extracting and selling what became known as Epsom Salts at extravagant prices – five shillings an ounce being recorded in 1640.

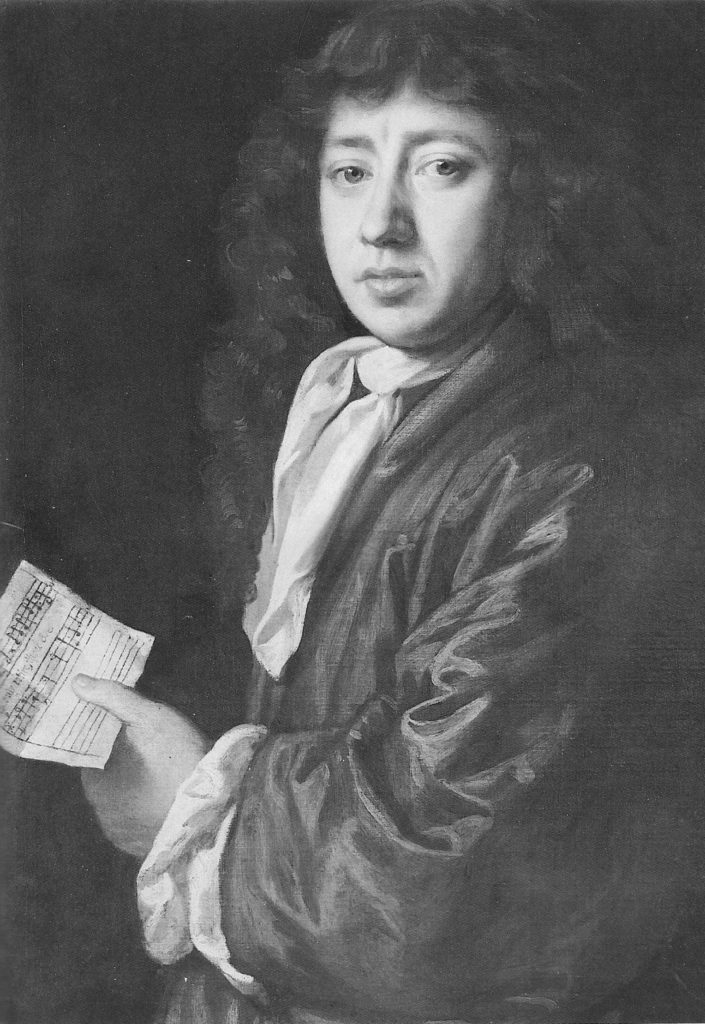

Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary of 1667, “We got to Epsom by 8 a-clock to the Well, where much company; and there we light and I drank the water; they did not, but do go about and walk a little among the women, but I did drink four pints and had some very good stools by it.” Later he visited the King’s Head, the nearest inn to the Downs, “where our coachman carried us; and there had an ill room for us to go into, but the best in the house that was not taken up; here we called for drink and a bespoke dinner. And hear that my Lord Buckhurst and Nelly (Nell Gwynne, the King’s mistress), is lodged at the next house, and keeps a merry house.”

Lord Buckhurst was described by Beauclerk as, “Cultured, witty, satirical, dissolute, and utterly charming”. Pepys reports the news on 13 July: “[Mr. Pierce tells us] Lord Buckhurst hath got Nell away from the King’s house, lies with her, and gives her £100 a year, so she hath sent her parts to the house, and will act no more.” However, Beauclerk later informs us “Nell Gwynne was acting once more in late August, and her brief affair with Buckhurst had ended.”

Pepys, himself was enamoured with Nell Gwynne and kept this Richard Thomson engraving of her as Cupid c.1672, above his desk at the Admiralty.

By the year 1690, after the many improvements made by Mr Parkhurst, Lord of the Manor, the village of Epsom had grown into a thriving town, and the humble shed originally erected for the convenience of invalids had now been replaced by a sumptuous ballroom.

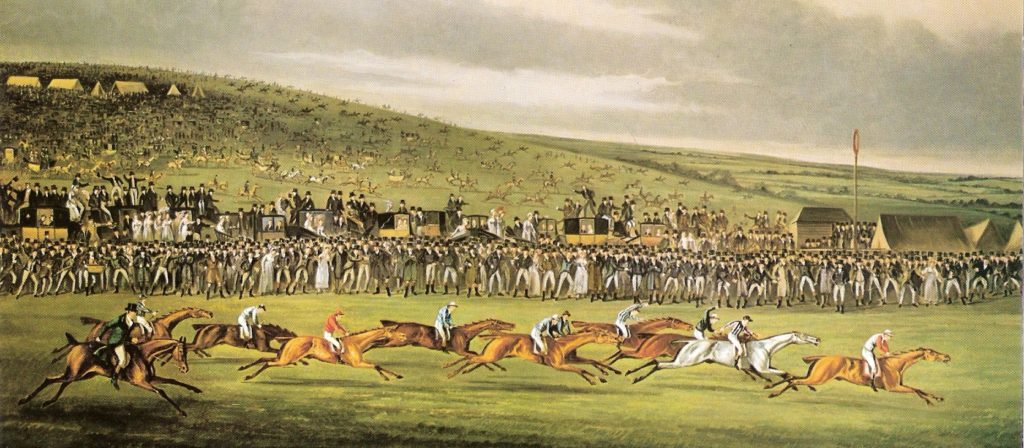

Henry Pownall, in his History of Epsom, published in 1825, said, “It became the centre of fashion; several houses were erected for lodgings, and yet the place would not contain all the visitors, many of whom were obliged to seek for accommodation in the neighbouring villages. Taverns, at that time reputed to be the largest in England, were opened; sedan chairs and numbered coaches attended. There was a public breakfast with dancing and music, every morning at the wells. There was also a (betting) ring as in Hyde Park; and on the downs, races were held daily at noon; with cudgelling and wrestling matches, foot races etc., in the afternoon. The evenings were usually spent in private parties, assemblies or cards; and may we add, that neither Bath nor Tunbridge ever boasted of more noble visitors than Epsom, or exceeded it in its splendour, at the time we are describing.”

The earliest indications of horseracing on Banstead (Epsom) Downs are in the 1640’s. In mid-May 1648, during the throes of the Civil War, the Earl of Clarendon in his History of the Rebellion relates, “a meeting of the royalists was held on Banstead Downs, under the pretence of a horse race, and six hundred horses were collected and marched to Reigate.”

This suggests that for such an undercover rendezvous to take place racing at Epsom must have been a regular and well-attended occasion. Under the Commonwealth (1649-60), horseracing was banned, but upon its demise, the first recorded race meeting in the country took place at Epsom on 7 March, 1661, in the presence of Charles II.

Two years later, on 27 May, Pepys wrote in his diary, “This day there was a great thronging to Banstead Downes, upon a great horse race and a foot race; I am sorry I could not go thither.”

Part Two

Following on from Samuel Pepy’s disappointment in not being able to attend Epsom’s races, there was however, an early 18th century account of an Epsom race meeting recorded by Conrad von Uffenbach:

“At three o’clock in the afternoon we rode out to the place where the races are usually held, called Banstead Downes near Epsom. We found there vast crowds on horseback, both men and females; many of the latter wore men’s clothes and feathered hats, which is quite usual in England…We were amazed that the racecourse was so uneven and hilly. All around, almost as far as the eye could see, were placed coloured sticks or posts, round which the horses had to run twice in one race… The five horses that were to run were first covered with blankets and led by hand round the paddock so that everyone might see them and the betting on the winner begin.”

A servant of Uffenbach then timed one of the four-mile heats at nine minutes, which greatly impressed their party.

In 1706, John Livingstone, having previously established himself as an apothecary in Epsom, purchased a plot of land in the town to build a pleasure-palace for dancing and gaming, adding a jewellers shop and a bowling green. Livingstone’s ambition went further. A distance from his amenities he sank a well, installed a pump and, with a great deal of publicity, laid underground pipes directly into his establishment. Furthermore, to ensure his success, he bought up the lease on the original well and then locked up the site.

Although tasting similarly foul, the new spring water had no medicinal properties. This however, did not stop Livingstone, who sent faked samples to reputable chemists to enhance the water’s reputation and, since the old wells were shut-up, no lawful comparison could be made.

In 1716, after two genuine mineral springs were discovered at Cheltenham, Epsom’s fortune went into decline, although in 1720, the time of the South Sea Bubble, Pownell relates, “There was, however, a temporary renewal of its former gaiety and dissipation….when the alchemists, Dutch, German and Jews, again filled the village; its balls and amusements were revived, and gaming with every other description of profligacy and vice, prevailed to an enormous extent.”

When the bubble burst, Epsom was again deserted, but in 1736, its fortunes took a turn at the arrival of a celebrated female bonesetter – Sarah Wallin – known to all as ‘Crazy Sally’. Apparently, she could put a man’s shoulder back without assistance and her success with fractures and dislocations caused the inhabitants of Epsom to raise an annual subscription of £300 a year to induce her to stay. She did for while but then, at the height of her fame, she fell in love with a Mr Hill Mapp, from Ludgate Hill – a footman and by all accounts a rogue. The marriage, strongly opposed by the Epsom residents, was a disaster, Mapp taking all her money and then abandoning her to die in a pauper’s grave in the London slum of St Giles.

A final effort to restore Epsom as a spa came around 1760, when a surgeon from London, Mr Dale Ingram, offered public breakfasts, washed down with a concoction of magnesia and Epsom salts. His success, however, was limited and many years later, in 1804, the buildings of the Old Wells were demolished and replaced by a private house.

Throughout the fluctuating fortunes in the town, race meetings on the Downs had become a regular feature in May and October from 1730, with prizes of cups and plates provided by the local nobility.

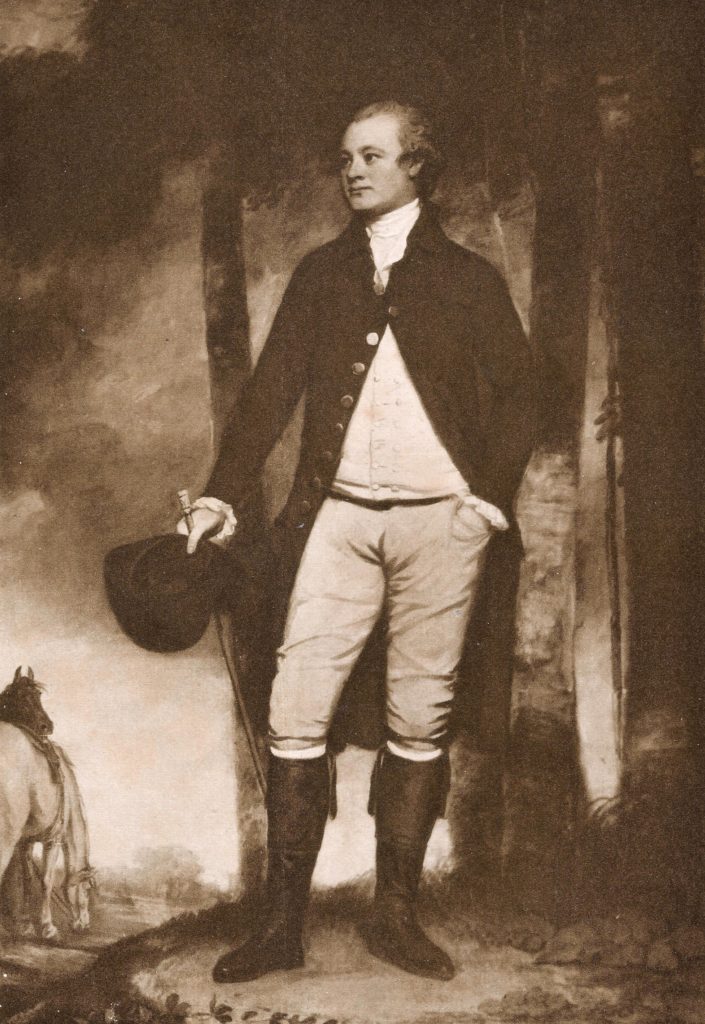

In 1775, a year after his marriage to Lady Elizabeth Hamilton, Edward Stanley leased The Oaks, a country house with 180 acres at Woodmansterne, near Epsom, from his uncle by marriage, General John Burgoyne. Burgoyne acting as a ‘father confessor’ to Stanley, ran the gamut of being a gambler, soldier, playwright and M.P. for Preston. However, on a wider plain, he is best remembered for surrendering Saratoga to the rebels in the American War of Independence, after which he became a prisoner of war.

In February, 1776, the 11th Earl of Derby died and Edward Stanley succeeded to become the 12th Earl. At the Epsom May Meeting in 1778, Lord Derby, who often acted as a steward at the meeting, invited a party of friends to his house, including Burgoyne, Richard Sheridan the playwright and Charles Fox, the prominent Whig politician.

Burgoyne, impressed with Anthony St Leger’s previous one-off sweepstakes at Cantley Common (forerunners of the St Leger), suggested to Lord Derby, that since the four-day race programme consisted solely of heats of either two or four miles, that the following year, a single race over one and a half miles for three-year-old fillies, would add some spice to the meeting.

12th Earl of Derby

The race named after Lord Derby’s house, The Oaks, was first run on Friday, 14 May, 1779 and was considered a great success, members of Lord Derby’s party all won money and that evening, another new race for both colts and fillies was planned for the following year. While there are no details in the archives at Knowsley concerning the foundation of the Derby, history has passed on the tale that the 12th Earl of Derby and Sir Charles Bunbury (the leading figure in the Jockey Club, who was staying at the Oaks) spun a coin as to whether the race should be called the Derby Stakes or the Bunbury Stakes.

The first running of the Derby Stakes was on Thursday, 4 May 1780. Open to three-year-old colts (8st 0lb) and fillies (7st 11lb), at 50 guineas each (half forfeit) and run over the last mile of the Orbicular Course. There were 36 subscribers and nine runners, and although Lord Derby won the toss of the coin, it was Sir Charles Bunbury who owned the first winner – Diomed.

In addition that day, a race for the Noblemen and Gentlemen’s Purse of £50 (for five and six-year-olds, run in three heats over four miles), was won by King Fergus, a future Champion Sire and son of Eclipse, who notably, sired three of the six winners at this four-day meeting.

The day’s entertainment also featured a main of cockfighting between the birds of the Gentlemen of Middlesex and Surrey, and those of the Gentlemen of Wiltshire. Enthusiastically supported by Lord Derby and his guests, cockfighting was at this time regarded the country’s principal sport, with results carried in the National press.

At the end of that day, no-one could have predicted that Diomed would provide the first link in a chain of winners extending over more than two and a quarter centuries, one that has made the Derby, together with the Oaks, the two oldest sporting events, continually run, in the world.

For more racing history see Michael’s Books for Sale.