The first Derby photo-finish

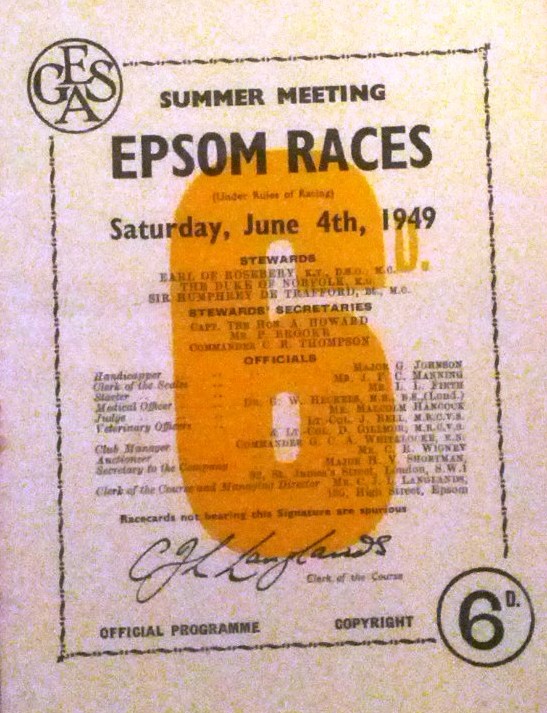

The first photo-finish for the Epsom Derby was in 1949.

The race was the focal point of the racing year and I was determined to be there.

Here follows an account of that day from the tales of my misspent youth.

“Are you going to the Derby next Saturday, Michael?” Don called across the smoke filled snooker room.

“Is the Pope Catholic?” I retorted, breaking off from lining up a red.

“I’ve got space in the old Humber,” Don added graciously. “I’ve just asked your Dad; he says it’s OK if I keep an eye on you.”

“Sounds super,” I replied, “much better than getting the coach.”

Just then, Master of Ceremonies, Bernie Stevens rang his bell, calling everyone back for the second half of the Whist Drive. This was Woking’s ambiguously named Railway Athletic Club, where, in these pre-bingo days of 1949, their Saturday night big-money drive was, along with the Atalanta ballroom, one of the two hot spots in Woking. My Father, Mother and Nan obviously preferred the Whist Drives: jitterbugging was never their strong suit, where as playing cards was as much a part of their life as queuing at the Co-op.

The Whist over, I got the Derby details from Don – pick up opposite the Railway Station, 10 o’clock sharp. Vicky, his fancy woman, (as Mum called her, among other things) and the Giant, were to be the two other passengers.

At this point, I must fill you in on my fellow travellers. Don was an ex-Guardsman, handsome, middle-aged and dashing. Vicky was four feet something, 40 going on 20, full of fun and covered in jewellery. Both were divorced and lived together in digs – this in the late 1940s was not only risque, but gave them a touch of celebrity. The Giant on the other hand was grotesque. Seven feet tall, and in his younger days a sparing partner to Primo Carnera, the 18½ stone Italian, who later became the World Heavyweight Champion. But now, bent almost double with arthritis, his face bore the scars of his profession and he was often referred to as Boris, after Boris Karloff of Frankenstein fame.

In spite of the journey being only 17 miles, it took us almost two hours to get to Epsom, and another half hour to park, this with every road jammed and crowd estimates of half a million people covering the Downs. Boris, for reasons of convenience, went straight into Tattersall’s, where he would sit high up on the steep terraced steps to watch the afternoon’s events, while Don, Vicky and I sallied around the funfair.

Don was drawn towards the rifle range where, after examining and changing his rifle, he hit four consecutive clay pipes. Vicky was delighted and so was I, although I respectfully declined the privilege of carrying the prize of a very large stuffed donkey around with me for the rest of the afternoon. We then had a go at the coconut shies, hoopla and rolling pennies down a shoot, but nothing doing. Vicky insisted that we all went on the Chairaplanes – rows of swings that rotated at speed. Don said that he and Neddy preferred to sit this one out, but asked me to accompany Vicky.

Once the wheel got up speed, all the chair-swings fanned out over the crowd; Vicky was shrieking and waving down at Don, but to me, it was terrifying. I seemed to remember reading about a young boy who had been flung off at a fair and killed. “What a way to go!” I thought, “and on Derby Day.” Eventually, when all the swings returned peacefully, Vicky was still in a state of high excitement, and bought us each a stick of candy floss.

“You look a bit pale Michael,” she said mischievously. I tried to grin, but felt as if I had passed through a near-death experience.

As we moved through the crowds, we saw an escapologist at work, an elderly man, thin but wiry looking. He was wrapped in chains, handcuffed and then put in a canvas sack, which was then padlocked. We watched and waited. From time to time we saw the sack wriggle about as crowds pressed in on all sides and the barker entertained the crowd with details of The Great Murcurio’s past feats. Then, slowly, a hush fell over the crowd, the sack was still. People began to murmur their concern; one woman shouted across to the barker,

“You’ve killed the poor old bugger, you rotten sod.”

To allay everyone’s fears, he went over to the sack and shouted,

“Is The Great Murcurio all right in there?”

There was no reply. The woman shouted out again, “Now you’ve done it, you rotten bugger, you’ve killed him, and all for a few bob.”

Don dashed off to find a Red Cross man, but no sooner had he gone, than the sack started to wriggle again. The barker wiped the sweat from his brow and by now the onlookers were pleading with him to open the sack. Then, as he removed the padlock, the old man sprang out of the sack like a jack-in-the-box. There was much cheering and great relief all around. Needless to say, the barker’s collection yielded a shower of silver and not a few ten-bob notes. When Don did get back, he said the Red Cross had been called every half-hour since nine this morning with the same story!

Vicky looked at her watch; it was one o’clock. The first race was in half-an-hour, so we scuttled off to squeeze into the old Stewards’ Stand opposite the main grandstand. Although you looked head-on down the course, it was a great place to watch the race from, and by now we were all pleased the enclosure had its own toilets.

Don and I were Gordon Richard’s fans, but Vicky just went by the horses’ names. Saucy Boy, ridden by an apprentice, caught her eye, and it caught the judge’s eye too, romping home at 6-1, while Don and I searched in vain for Gordon at the tail end of the field.

In the next race, another five-furlong sprint, Gordon rode the Aga Khan’s Malindi, which Don and I both backed, in spite of the odds-on Lightning Sketch. When I say we both backed, in reality it was Don who put the money on, as a skimpy 13-year-old would have been, rightly or wrongly, turned away. Anyway, Malindi won at 7-2, with the favourite finishing last of five.

There was now an hour before the big race, the sun was shinning, there was just a slight breeze, and then as now, there is no finer place to be than on Epsom Downs on Derby Day.

In order to see the parade, we squeezed in on the terraced steps as the 32 runners filed before us. To make the most of this occasion, I had painted their colours in a little notebook, as racecards of the day were printed in black and white and had no pictures.

Having had an ante-post bet on Lord Derby’s Swallow Tail after he had won the Chester Vase, I was content to have a saver on Gordon, who was riding the 9-2 favourite Royal Forest. Don also backed Royal Forest, but Vicky, being an admirer of the glamorous Suzy Volterra, backed her husband’s horse, Amour Drake. Also fancied was the Two Thousand Guineas winner, Nimbus, owned by Mrs Marion Glenister and ridden by Charlie Elliott.

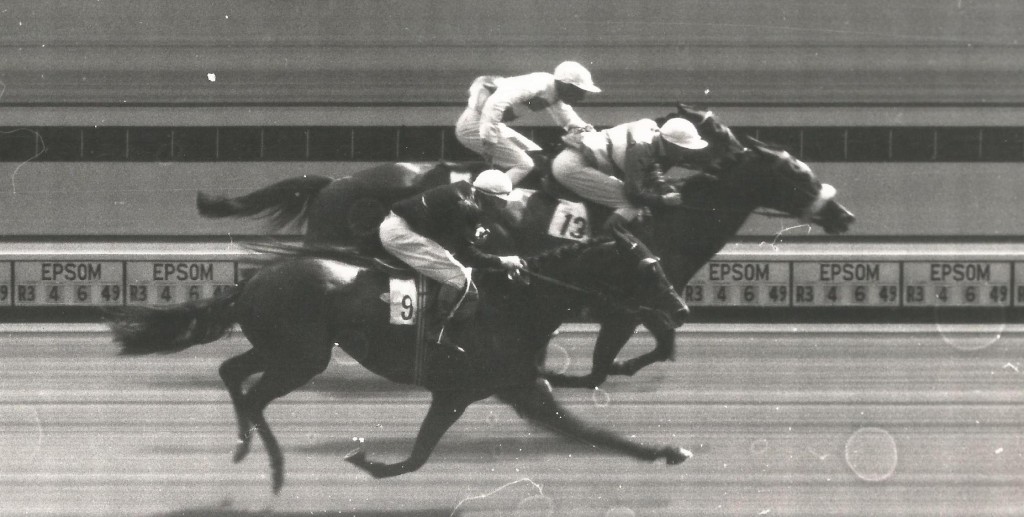

Unable to get to the top of the terraces, we got our first glimpse of the race as the runners came around Tattenham Corner. Nimbus and Swallow Tail were clear. Inside the final furlong, Swallow Tail gained the advantage. But Nimbus, on the rails, gamely fought back, before tiring and drifting across towards the stands, taking Swallow Tail with him. Meanwhile, Amour Drake, having been 10 lengths adrift earlier in the straight, came storming up the centre of the course on to the heels of the front two. His jockey, Rae Johnstone, finding his path blocked, had to switch Amour Drake to the rails, losing both ground and momentum. A desperate battle ensued over the last 50 yards with all three contenders crossing the line together. “Photograph, photograph,” it was to be the first in the history of the Derby.

I was sure Nimbus had won, but many around me thought Amour Drake had; further down the terraces, would be those who thought Swallow Tail had held on. And although the race was over and I had lost my bets, I immediately saw an opportunity of making a profit on the Derby. Urgently, I persuaded Don, another man of chance, to walk ahead of me along the first two rows of the terraces to call out, “I’ll lay evens Amour Drake and 3-1 Swallow Tail.”

Those around us were keen to hedge their bets and some were confident of their eyes. As Don took the money, so I wrote the bets in my note book, adding the punters’ names, for we had no tickets to give out. The result of the photo took so long that Don took about two dozen bets, mostly pound notes.

“I hope you’re sure about this Michael,” said Don, realising we might not have enough money to pay out if I’d got it wrong.

I didn’t have to answer; suddenly the result frame was being hoisted up, and at the top was number 13, Nimbus; 26 Amour Drake was second and Swallow Tail third.

“How much have we won?” I said excitedly.

“Well done,” replied Don, “I was beginning to get worried; it took so long.”

“How much,” I persisted.

Don gave way and emptied his pockets.

“Twenty-two pounds. How do you want to split it?” he said.

I paused, “How about a tenner each, and two quid for a slap-up supper?”

Soon a rumbling roar went up over the Downs, as various sections of the crowd were relayed the result.

I tugged on Don’s sleeve: “Come on, we’ve got to get out of here, in case someone has reported us to the ring inspector.”

Fortunately, many others were leaving the enclosure at the same time, so our exit was not conspicuous. Very soon, my 13-year-old brain was buzzing with the potential betting opportunities surrounding this new technology. What a wonderful thing this photo-finish is!

We decided to join the Giant and, in spite of the gateman’s reservations, Vicky and her donkey charmed us through the entrance. It was more crowded than the enclosure we had left, but we knew roughly where the Giant would be and he wasn’t difficult to spot. Vicky saw him first, towering above the rest, eating a tiny ice cream cone like a big kid. I’m sure, if he had wanted to, he could have held a dozen cones in one hand.

“Back any winners Boris?” Don asked, as the runners went down for the next.

“Not yet Don, but you’ve just missed the sight of the afternoon – Rita Hayworth.”

Vicky was all ears.

“You know she married Prince Aly Khan earlier this year? Well, he bought her a horse as a wedding present – But Beautiful – it’s running in the next. I watched her walk down the line of bookmakers; everyone was speechless, not a word and, no-one struck a bet.”

“Well someone’s backed it,” I said. “It’s showing odds of 4-7 now.”

A minute later, But Beautiful and the Duchess of Norfolk’s Suivi headed the field at the furlong marker and, after a thrilling finish, passed the post together – another photo finish. Not so long to wait this time; first Suivi. We decided to stay put for the rest of the afternoon, sitting on the terraced steps. Favourites won both the last two races, with ‘Last race Cook,’ living up to his monicker and coasting home four lengths ahead of Doug Smith.

There were many unseen dramas that followed that afternoon, some we heard of in days, others months and one, over three years later, when Mr Henry Glenister committed suicide in his car in Sussex. Glenister was an employee of the Midland Bank when he paid 5,000 guineas (equal to £190,000 today) for Nimbus as a yearling, as a present to his wife. Later, the inquest revealed that Glenister had defaulted on ‘a considerable sum’, although the extent of the fraud was never made public.

A more poignant end had taken place the day after the Derby, when Suzy Volterra returned to her dying husband in Paris. Leon, whose health had suffered during wartime internment by the Germans, had been too ill to listen to the broadcast, and so, before his death, his wife allowed him to think his colt Amour Drake had won the Derby.

This account of the 1949 Derby

comes from Michael’s book of short stories

Born To Bet

To see more of Michael’s books go to Books For Sale