Epsom Racecards & Betting

Following the first 50 years (1780-1829), the Derby had become firmly established as the premier event in the racing year. The old format of two and four-mile heats was being replaced with single races over a variety of distances and two-year-old races were becoming popular. Race meetings, such as Epsom, Newmarket, Ascot, Chester and Doncaster, were no longer run entirely by and for the aristocracy, but attracted an interest from a wider public. Fuelled by Bell’s Life, the general public would slowly, but increasingly, have knowledge of the more important race meetings and the results.

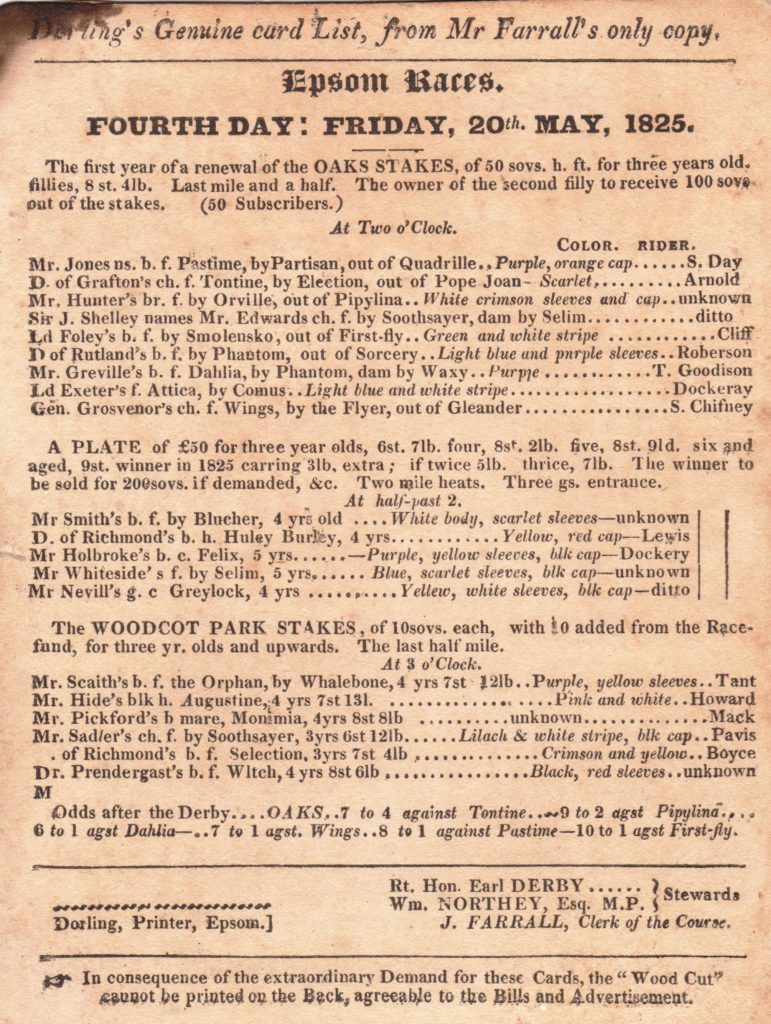

From 1825, local printer William Dorling produced a racecard – “Dorling’s Genuine Card List”, also known as “Dorling’s Correct Card” – a seller of which can be seen in William Powell Frith’s painting of ‘The Derby Day’. The racecard, revolutionary at the time, not only gave the list of runners, but also their owners, pedigrees, jockeys, colours and, for the major races, the ‘state of the odds’.

The point of sale for these racecards was The Spread Eagle in Epsom’s main street. There in the courtyard of the last coaching stop before ascending the hill to the course, assembled owners, grooms, jockeys, together with some of the darkest element of the betting fraternity. Many of the racecard sellers who worked around The Spread Eagle had their own eccentric and sometimes dramatic identity.

The “King of the card-sellers”, was known as Jerry, who either as a Broadway dandy wearing a hugh straw hat, or a captain wearing a red coat and brandishing a spy-glass, would cling to the side of the carriages, mimicking the dandies and swells, while pocketing their sixpences. Sadly, one day in a moment of zeal he pulled a carriage over on top of him, causing havoc in the street and ending his life. Another card-seller was called ‘Donkey Jemmy’, his act was to wear a bright yellow wig and bray like a donkey. He would not bray for everyone though, as he would explain with pride – “I do the donkey to please the aristocracy, not the common people.” Other sellers who frequented The Spread Eagle were ‘Sailor Jack’, who played up a disfiguring squint and lack of knowledge on nautical matters, and the eccentric ‘Lord Castlereagh’, who although eating dry bread himself, would cook beef steaks for his French poodle. Finally, let’s not forget Fair Helen, ” a handsome dame she was too with her fine black hair” and who’s charm, it was said, could sell more than 700 racecards in a week.

The coaches ascending the final mile from The Spread Eagle to the final toll-gate had to pay £1. This would admit any vehicle onto the Downs for a day. Later, in 1830, as part of the promotion of the new grandstand, coaches could be driven right up to its steps as part of “a finish in style.”

The following racecard – Oaks Day 1825, winner Wings – discovered by fellow historian, John Slusar, is thought to be the earliest existing copy, recently usurping the racecard of Derby Day 1827.

The Dorlings’ influence at Epsom lasted nearly a century. William’s son Henry became Clerk of the Course in 1839, until his son, the thoroughly unpopular Henry Mayson Dorling, took over and kept the position until his death in 1919.

Returning to the mid-19th century, the railway system would not only revolutionise horse travel, but sportsmen would be able to travel from course to course in comparative comfort. Against this background, however, grew increasingly unscrupulous elements, such as thugs paid to make the favourite ‘safe’, crooked jockeys in the pay of ‘legs’ (early bookmakers) and con-men in many guises, who would stop at nothing to part both the aristocracy and the tradesmen from their money.

On a higher level, Charles Greville, the Whig aristocrat, wrote in his diary:

“I grow more and more disgusted with the atmosphere of villainy I am forced to breathe…it is not easy to keep oneself undefiled. It is monstrous to see high-bred and high born gentlemen of honoured names and families, themselves marching through the world with their heads in the air, all honourable men, living in the best, the greatest and most refined society, mixed up in schemes, which are neither more or less than a system of plunder.”

Villainy on the Turf reached a new peak in the Derby of 1844, when the apparent winner Running Rein, owned by Mr A. Wood, a respectable Epsom corn-chandler, was in reality a four-year-old named Maccabeus. With Lord George Bentinck unravelling their plot and successfully pursuing the villains to the Court room.

The Running Rein Scandal has its own chapter later in the book.

Reformation & Revolution in Betting

Racing in its present form could not have survived without betting, therefore, the positive move that started an avalanche of reformation after the nadir of the 1844 Derby, given time, allowed owners and breeders to plan for the future and encouraged the general public to follow their sport with a degree of confidence. Prophetically, on the Monday of Derby week in 1844, a notice from the Police Superintendent of Scotland Yard was circulated amongst the proprietors of the gaming marquees and betting-houses being hastily erected on Epsom Downs. It stated:

“All persons playing or betting in any booth or public place, at any table or instrument of gaming, or at any game or pretend game of chance, will be taken into custody by the police and may be committed to a House of Correction, and there kept to hard labour for three months.”

The Government then tried to enforce dual standards on who could or could not bet. They argued that “the upper classes had the money and leisure not to be corrupted by betting, but that for a working man gambling losses would lead to crime.”

But in spite of the Governments heavy-handed judgment, betting continued at all levels. Around this time there sprang up “list bookmakers”, who, defying the law, would pin up their lists of runners and prices and take bets in the pubs, bars and clubs, some even nailing them to trees in the popular London parks.

The father of modern bookmaking, William Crockford (left), owned and ran Crockford’s Club (see illustrated below) in the heart of Mayfair. He also ‘made a book’ at the club and specialised in laying green young bucks “a thousand pounds to ten” they couldn’t name the winners of the future Derby, Oaks and St Leger. Said quickly, it might sound attractive, but only if the odds were to average less than 4-1 a piece!

One of the most popular forms of betting at this time was the big-race sweepstake and the Derby Sweep was the most popular. Then, as now, people paid for a ticket in the hope of ‘drawing’ a horse and collecting a handsome cash prize if they won. These sweeps could be found in almost every town in Britain with pubs and clubs the most popular venues. Stakes would vary from thrupence or sixpence in the poorer places, rising to £100 in the smart London Clubs.

Due to the reforming elements of the new administration, from the mid-19th century to the opening of betting shops in 1961, the only lawful way to bet on horseracing was either to attend the track or to possess a credit account with a licensed bookmaker. However, since the latter required the punter to have a bank account, references and, a regular income, most people opted to bet with cash through an undercover network of bookmakers’ runners.

Course betting also had its disadvantages in the cheaper enclosures and on the open downs, where the less reliable or more speculative bookmakers would sometimes abscond (‘do a runner’), when unable to pay out. Beatings, and in later years slashed tyres, were often the punters ‘remedy’ in such circumstances!

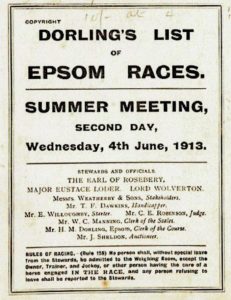

Racecards were very basic, printed in black and white and showed only the early declarations, making it necessary to cross out, sometimes a third of the runners. Interestingly, the 1913 (Suffragette) Derby racecard still called itself Dorling’s List. Later, as a schoolboy racegoer from 1948, I would paint the jockey’s colours into a notebook in order to identify the horses in the Derby parade. It seemed essential, since the first full colour racecard did not appear until 1995!

Racecards were very basic, printed in black and white and showed only the early declarations, making it necessary to cross out, sometimes a third of the runners. Interestingly, the 1913 (Suffragette) Derby racecard still called itself Dorling’s List. Later, as a schoolboy racegoer from 1948, I would paint the jockey’s colours into a notebook in order to identify the horses in the Derby parade. It seemed essential, since the first full colour racecard did not appear until 1995!

The Tote first operated on Derby Day in 1930 and was not only welcomed for its win and place pools, but considered a safer alternative to some bookmakers on the hill. The game-changing introduction of betting shops in 1962 was inevitably followed by the progressive taxation on winning bets. In recent years, however, the wheel has come full circle. The Government’s abolition of betting tax in October, 2001, combined with the revision of gambling laws the following March, brought about a staggering increase in turnover.

Meanwhile, in 2000, with the idea of launching a betting exchange, Andrew Black and Edward Wray, had secured £1m of investment from friends and family to become the co-founders of betfair.com. Betfair would operate on the principal of a financial exchange, combining many small bets in order to lay a gambler a large bet, or vice versa.

Although other exchanges followed, within a few years Betfair had 90% of the betting exchange market in the UK. Then in 2010, successful and fully established, Betfair was floated on the London Stock Exchange, with a share price of £13. This rose to £44 before Betfair was delisted when merging with Paddy Power in 2016.

With Great Britain now the gambling capital of the world, what will be the next innovation?

![]()

![]()