William Powell Frith was born in Aldfield, North Yorkshire in 1819, and although keen to be an auctioneer, was encouraged by his parents to take up art.

William Powell Frith was born in Aldfield, North Yorkshire in 1819, and although keen to be an auctioneer, was encouraged by his parents to take up art.

As a lad of 16, armed with a portfolio of drawings, he was accompanied by his father, an innkeeper in Harrogate, on a 24 hour stage-coach journey to London. There he studied at Sass’s Art School, going on to win a place at the Royal Academy Schools in 1837, and becoming a full Academician in 1852. Success quickly followed when Queen Victoria bought the first of his large scale narratives, Ramsgate Sands.

On his first visit to a racecourse – Hampton – in 1854, he was struck by the contrast of human life there. In particular, a gypsy family enjoying a large Fortnum and Mason’s pie and to his horror an unsuccessful punter attempting to cut his own throat.

Frith’s first attended Derby Day in 1856, and whilst he admitted to having no interest in the race, he spent the afternoon studying the people – the card sharps and ‘thimble riggers’, the acrobats, minstrels, gypsy fortune-tellers, young bucks and carriages filled with beautiful women. Later, with the assistance of Robert Howlett’s photographs of Derby Day crowds lining the straight, he began work on the painting

On seeing the sketch for Derby Day, Mr Jacob Bell paid Frith £1,500 to paint him the picture and a Mr Gambart paid him a further £1,500 for the copyright of the engraving.

The work was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1858, after which Frith wrote:

“When the Queen came into the large room, she went at once to mine; and after a little while sent for me and complimented me in the highest and kindest manner. She said it ‘was a wonderful work’, and much more that modesty prevents me repeating.”

Frith’s painting proved an enormous attraction at the Exhibition as snippets from his diary tell:

May 2 – Private view. All the people crowd about the “Derby Day”.

May 3 – Opening day of the Exhibition. Never was such a crowd seen round a picture.

The secretary obliged to get a policeman to keep people off. He is to be there from eight in the morning. Bell applies to the Council for a rail which will not be granted.

May 7 – To the Exhibition. Knight tells me a rail is to be put round my picture. Hooray!

May 8 – Couldn’t help going to see the rail, and there it was sure enough; and loads of people.

After the Exhibition, the owner of the copyright, Ernest Gambart, organised a huge publicity campaign, sending the painting on tour, first to the provinces then to Europe, finally culminating in a tour of the United States and Australia. At that time, very few paintings had achieved comparable fame and it was generally recognised that Frith had faithfully captured the manners, dress and behaviour across the classes at a world famous event. Walter Sickert, the post-impressionist painter, said in 1922, the painting was, “the most popular…. the most unaffectedly enjoyed picture in the collection,” of the National Gallery.

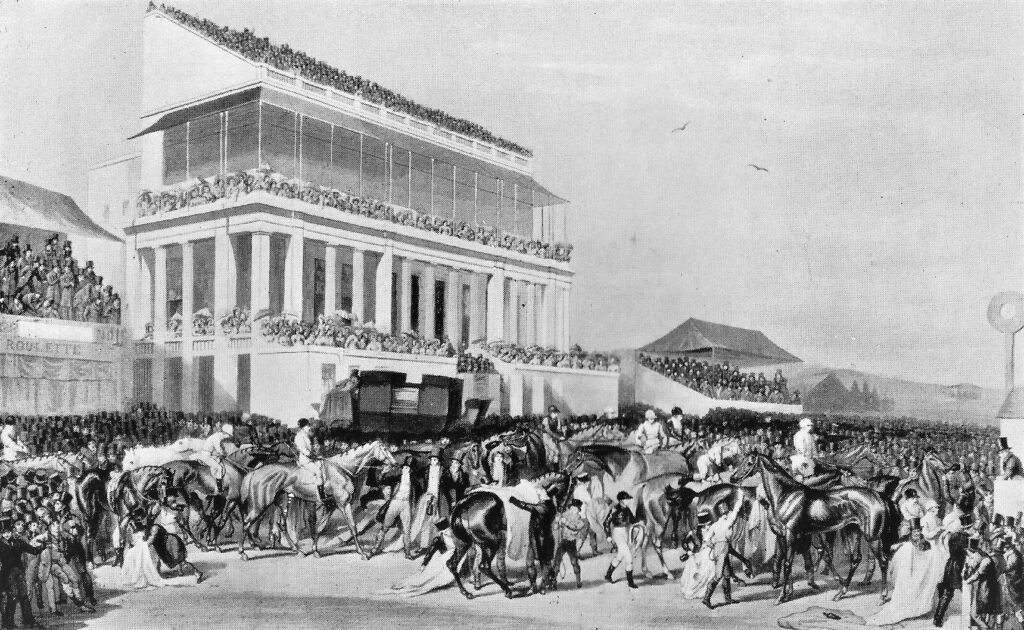

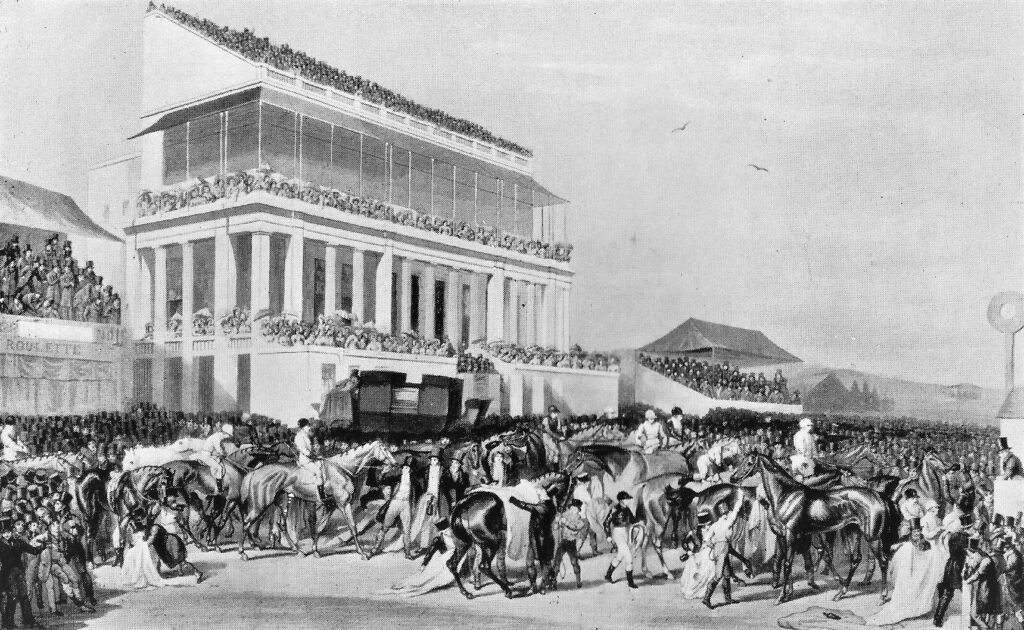

To appreciate the painting in detail I have divided it in to four sections below, together with a close-up picture of the horses being saddled in front of the new grandstand.

The tents on the left housed various gambling set ups including E O, a form of roulette where the individual numbers were replaced by an E for even numbers or an O for odd numbers, each paying even money with one zero for the house. This prevented the owners from paying out large sums on individual numbers.

In the centre a thimble rigger plies his trade, while to the right of the pennyless boy, card sharps tempt you into another “easy money” card game. Above the white dog an accomplice shows the money he has supposedly won. Meanwhile at the foot of the next picture, gypsy children cradle a baby.

William Dorling, a local printer, produced from 1825, a racecard known as “Dorling’s Genuine Card List” – a seller of which can be seen holding the card aloft to the left in the picture. The racecard, revolutionary at the time, not only gave the list of runners, but also their owners, pedigrees, jockeys, colours and, for the major races, the ‘state of the odds’. The point of sale for these racecards was The Spread Eagle in Epsom’s main street. There in the courtyard of the last coaching stop before ascending the hill to the course, assembled owners, grooms, jockeys, together with some of the darkest element of the betting fraternity

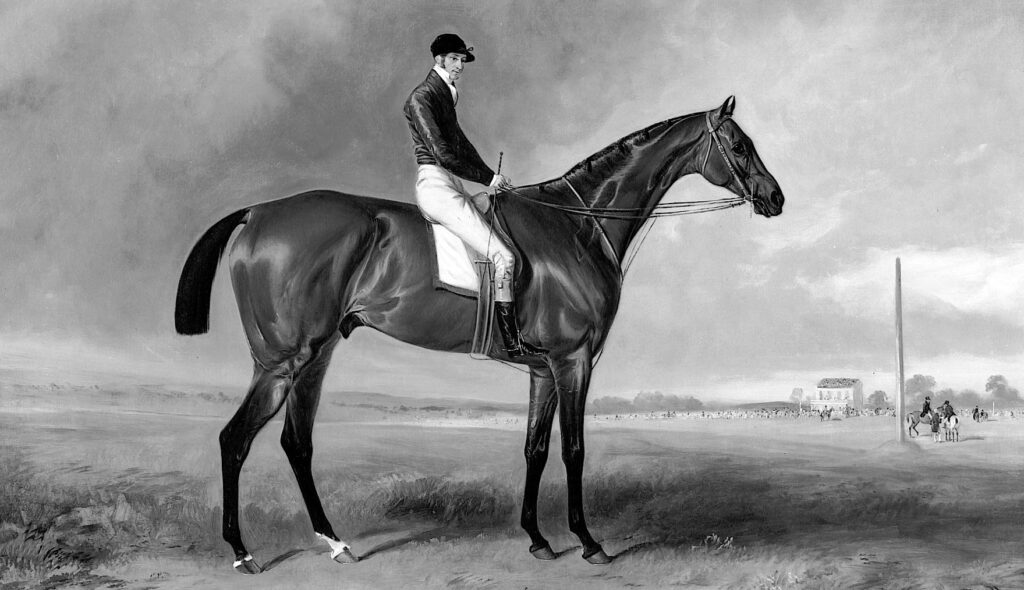

In 1845, with the Epsom Grandstand running at a loss, William’s son Henry, a prominent share holder in the new grandstand, came up with the proposal, with support from Lord George Bentinck and negotiations with the Grand Stand Association Committee, to put the racecourse back on a sure footing. This that all races be saddled in front of the Grandstand (see below); proposing an additional £300 to the prize fund and making improvements to the lawn and accommodation in the Grandstand. Previously, saddling had taken place in ‘The Warren’, where the horses surrounded by well-wishers often prevented the jockeys finding their mounts, so causing considerable delays.

The move became an instant success, insuring a packed Grandstand of 5,000, in order to see what was popularly known as ‘The Preliminary Canter’.

The more wealthy racegoers now enjoyed the benefit of seeing the horses saddled, then cantered down the straight and back to the start.

Behind the fashionable ladies and the hungry boy, the horses are about to turn back to the grandstand in what was known as “The Preliminary Canter.”

It was generally accepted that although very few of the crowd saw much of the racing, the attraction was just being there!

Barefoot gypsies try to sell a posy to rakish toff and his embarrassed companion, while a character under the coach reaches out for the dregs of a bottle. In the background an acrobat balances on a tall pole for pennies.

Despite his wonderfully observed painting, Frith was not really interested in horseracing and across the scene there are no sign of the bookmakers. However, years later, an etching study of rails bookmakers at Ascot, entitled The Road to Ruin appeared in 1879.

Although Frith appeared to be a pillar of Victorian society, like most artists he was far from an open book.

Living with his wife Isabelle in the London district of Bayswater, they had 12 children. Nevertheless, unbeknown to Isabelle, William started another family with Mary Alford only a mile away, where he sired a further seven children. For many years, Isabelle had no suspicion of her husband’s infidelity, until one day, when he was supposed to be on holiday in Brighton, she caught him posting a letter close by their home. What agreement they came to was never published, but soon after Isabelle died in 1880, William married Mary.

William Powell Frith died on the 2nd of November 1909 at his residence in St Johns Wood, and is buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, in North Kensington, London.

For more Racing History see Michael’s Books for Sale.

William Powell Frith was born in Aldfield, North Yorkshire in 1819, and although keen to be an auctioneer, was encouraged by his parents to take up art.

William Powell Frith was born in Aldfield, North Yorkshire in 1819, and although keen to be an auctioneer, was encouraged by his parents to take up art.