The Ghostly Lieutenant

Father Perry Green and his housekeeper, Emily, having spent the morning taking down the Christmas decorations, were carefully wrapping the crib figures in tissue paper and boxing them up for next year.

The tree had been a bit of a problem – an artificial, three-part, screw together, measuring eight feet high. Not Father Perry’s idea, but Emily had insisted, “I haven’t time to hoover up pine needles for the twelve days of Christmas.”

So now, having forcefully crammed the tree back into its original box, it joined the other packages on the landing, waiting for Father Perry to put them in the loft.

A few days later, not having visited the loft since moving into his new residence, Perry was keen to tell Emily what he had found up there.

“It’s terribly dusty, nothing has been disturbed for years – rolls of carpet, tatty curtains, old picture frames; no lights of course, but there is a skylight window and under it, there’s a card table, a wicker chair and a pile of old newspapers. It looks as if many years ago someone went up there to study. Oh, and I think we might have mice too. I will have to ask the council to send around the pest controller.”

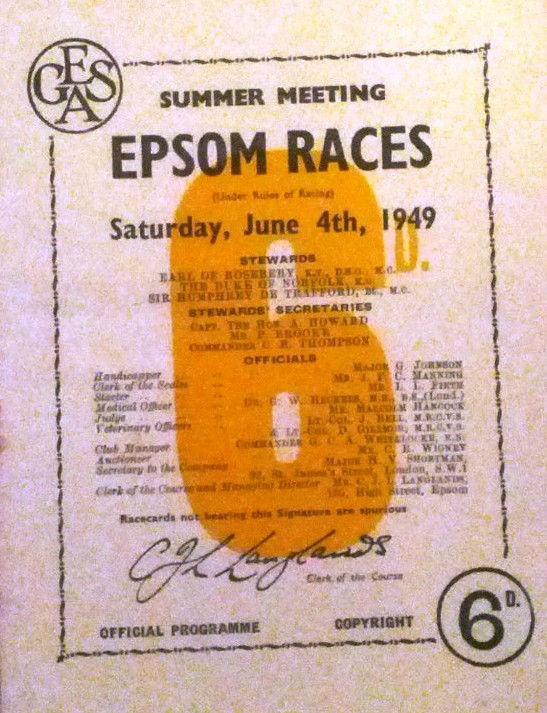

The following Saturday, there was jump racing at Ascot on TV.

Father Green had come back with the Racing Post and was looking forward to studying the form. However, no sooner than he had summed up the first race, Emily’s brother, Donald, arrived to tidy the garden, rake up the leaves and burn them.

Perry became restless and felt guilty reading the racing pages while Donald was working, so to ease his conscience, he went out to make himself useful.

An hour or so later, with Donald gone and the leaves gently smouldering at the bottom of the garden, Perry thought he just had time to find a winner.

“Have you seen my Racing Post, Emily?”

But no, she hadn’t, and after he had made a thorough search, his frustration became evident when, on turning on the TV, he learned that the only horse

he had picked out – Mark Pitman’s Hitman – had won at 20-1.

That night, while lying in bed, Father Green was disturbed by a scampering in the loft, not much and not often, but just enough to add to his irritating day.

Monday morning, after mass, Father Perry went out to buy four mouse-traps and on returning, climbed up into the loft to prime them with Sainsbury’s mature cheddar.

The manoeuvre to set the first three entailed Perry crawling around on his knees with a torch for ten minutes. But then, with a touch of flair, he planned to set the final trap on the table under the skylight.

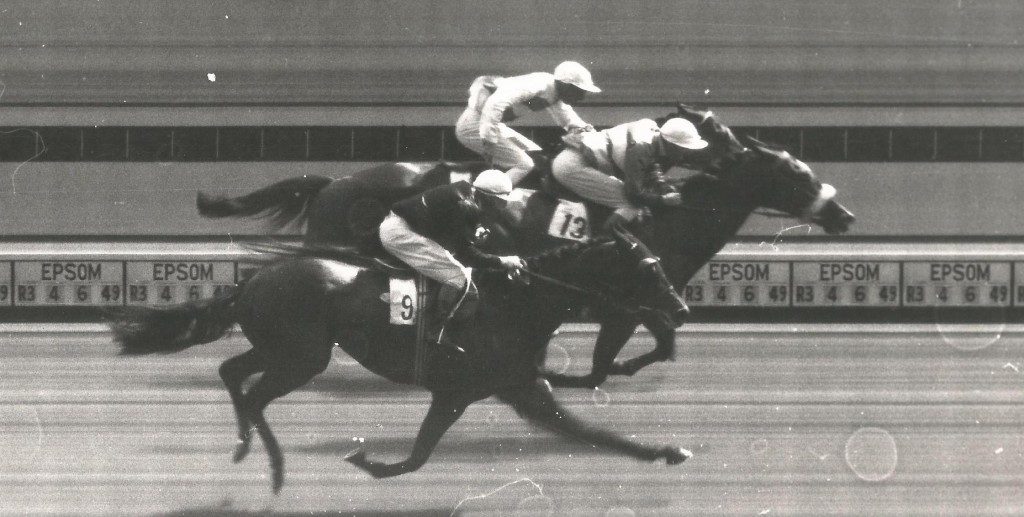

Approaching the dusty card table his eyes fell upon a half-opened Racing Post. He checked the date – it was Saturday’s.

“That’s impossible,” he uttered, then, instinctively, he turned the pages to the Ascot form, and instantly recognised the circle he had drawn around Hitman.

Trembling slightly and feeling angry, he tried to reason how the newspaper he couldn’t find on Saturday had now appeared in the loft.

After priming the fourth trap, Father Perry descended the ladder still in a state of bewilderment. Then, sitting down heavily on a kitchen chair he told Emily of the mystery.

Whilst making the tea she shot him an old fashioned look, before posing, “Are you sure you didn’t go up there before Donald came; you’ve been going on about those mice for days?”

Still a little confused, Father Perry knew he hadn’t and didn’t bother to answer.

The next day, as soon as Emily went shopping, Perry decided to take another look in the loft. He had told himself it was to see if the traps had bagged a mouse or two, but in truth he was still mystified by the reappearance of his Racing Post.

Taking a torch, he checked the first two traps – one tiny mouse.

“Looks like they’ve started breeding up here,” he thought. Then, glancing across to where the light partially covered the table, he thought he could dimly make out a figure hunched in the wicker chair. He took a half step and leaned forward, to be sure. Suddenly, the chair creaked and a figure in a military uniform half turned his head to gaze in his direction. Perry recoiled in horror. Half of the man’s face had been shot away, there was no blood, but the face had a grey ghoulish look. Father Green, now transfixed four yards from the vision, spoke out – his faltering voice sounding distant and hollow.

“Who are you, and, and w-why are you here?”

The man then got to his feet and slowly raised his arms above his head, as in an act of surrender. Perry, mesmerised, focussed all his attention on the image in an attempt to remember every detail, but then, after six or seven seconds, the man whose uniform Perry now recognised as an army Lieutenant, slowly faded away.

“Father, are you in the loft, Father?”

Emily had returned laden from the shops and called up for some help to put the groceries away.

When Perry came down, he said nothing, putting away the shopping as if in a trance. Meanwhile, Emily, sensing that he was preoccupied waited, until eventually asking, “How are the mice up there – still running around?”

Perry remained pale and preoccupied.

Then putting his hand on her shoulder said, “Sit down a minute Emily.”

They both sat down.

“Look, I don’t want you to think I’m going mad, but, I have just seen what I think was a ghost in the loft – a military man, badly wounded.”

Perry held the corner of the kitchen table for support while he continued, “I believe he might have been a Lieutenant in the First World War.”

Emily listened, reserving her credence and watching poor Perry’s face while he tried to make sense of what he had just seen. And although they both made an effort to normalise the rest of the day, the thought of the ghostly Lieutenant returned in every quiet moment.

The next morning, soon after Perry had gone out for his Racing Post, Emily, courageously pulled down the loft ladder, “To see for myself,” she mused.

“Father Perry was right about one thing,” she thought, “it was terribly dusty.”

Then, flashing a torch about her, she saw the dead body of a mouse caught in a trap.

“Yuk!” she recoiled.

Seconds later, she heard a rustle of paper and instinctively thought it was another mouse, or worse still, a rat. But slowly, almost unwillingly, her eyes went to the far end of the loft. And there, under the murky skylight, she saw him. Dignified in appearance and in his mid-thirties, he took no notice of her and carried on reading his newspaper.

“It was true, he was wearing a military uniform,” but then, after remaining motionless for what seemed like a full minute, she nervously called out, “Can I help you, Sir?”

He neither moved, nor spoke.

Then, as he slowly faded before her eyes, she had the strangest feeling that he belonged there.

Carefully, she made her way back and down the ladder. Where feeling numb from the experience she flopped into a chair and gazed blankly out of the kitchen window.

“So it really was true,” she told herself, “Just as Father Perry had said.”

Slowly, her validation of the vision led her on, and Emily, being Emily she soon became troubled with the responsibility of it.

While waiting patiently in the kitchen her mind darted to and fro over her experience, honing it in order to add to Father Green’s first encounter. But where had he got to?

When eventually Father Green came through the door, he sensed from Emily’s expression she had been waiting for him. Apologising and explaining that he had dropped in on a sick parishioner, he put the kettle on, while Emily, anxiously at first, told him her story.

After a while, when she had run out of things to say and Father Green had nothing more to add, they agreed that a drive and a walk around Victoria Park would help them put things into perspective.

“Blow the cobwebs away,” said Emily, taking charge of the situation, “You’ve been too long worrying about St Joseph’s and that silly diocesan survey, and now this. A good long walk in the fresh air is what’s needed. I’ll put together a picnic.”

Vicky Park, as it is known locally, was bathed in a watery sunlight and sitting on one of the benches by the lake, Father Green and Emily ate their sandwiches and fed the ducks. Oddly, they took on the appearance of a married couple after a disagreement, however, there had been no disagreement, only disbelief.

They spoke very little, each in their minds revisiting the appearance of their ghostly lodger.

There were very few people in the park that day, but Father Perry commented on the two soldiers taking a stroll.

“You know, there can be very little peace in an active soldier’s life and those who fight in close combat must remember those violent images for the rest of their lives.”

Then as an afterthought, “And what of the loved ones left behind?”

Suddenly, he recalled the childhood memory of the framed blood stained photograph on the mantelpiece of his great aunt Maud. Once she had told him that her husband, Walter, when fatally wounded in the trenches at Mons, had held it up in front of him, before he died.

Father Perry, a very gentle and fearful man, told Emily, “I would surely have suffered nightmares if I had witnessed those bloody battles at close hand.”

Emily, touched by his sentiments, supported and sympathised with him, until finally, she diverted the topic to her idea that perhaps, the ghostly Lieutenant had lived in the house some years before.

“We could check on that, I suppose,” said Perry, thoughtfully, “I’ll go to the Council Offices tomorrow, and ask if they have a record of past occupants.”

“While you are there,” lightened Emily, “would you ask them to send a pest exterminator – who knows how many mice we’ve got up there now?”

Father Green’s enquiries were absorbing. In fact, he was soon spending more time at the Council Offices than at St Joseph’s. Nevertheless, with time put to good effect, he had made steady progress.

Apparently, a Mr and Mrs Henderson-Bell had lived there with their son, Roland, until 1913. They then went to live in Canada, leaving Roland behind, until he joined the Army a year later. Further records showed the house as purchased by the Army in 1919.

Then, suddenly remembering the ever-growing patter of tiny feet in the loft, Perry made an appointment for the pest exterminator to call.

A week later, a ring at the front door brought in Mr Horatio Smallwood, the tall, thin, weasel-like, pest exterminator from the Council. His ID checked, Father Perry welcomed him in, introduced him to Emily, then took him upstairs to the loft ladder. Neither Father Perry nor Emily made any mention of their ghostly lodger, and once Mr Smallwood was in the loft, Perry, rather than accompanying him, nervously hovered at the foot of the ladder, praying that the Lieutenant would not put in an appearance.

After what had seemed the slowest 20 minutes in Father Perry’s life, Smallwood, having replaced the traps with rat poison, descended. Whereupon, Perry, after scrutinising the weasel’s face for signs of a sighting, gave grateful thanks. In the meantime, Mr Smallwood washed his hands, asked for a ‘job done’ signature and, before Perry’s heartbeat had returned to normal, was gone.

Having as he thought, his obsession with the spectre under control, Father Green returned to the loft the following week. Sure enough, there was no sign of mice. Mr Smallwood had told Perry that when the mice ate the poison they would scuttle back to their holes to die.

However, the question that had troubled Perry’s mind was silently answered when, under the skylight all that was visible was an empty table and chair. Still requiring proof, he again looked hard, looked away and refocused – nothing.

For a moment, he stood there bathing in the relief. Then, torch in hand, he walked across to where the spectre had been. His old Racing Post was still there, but with it, he found a pile of very old newspapers, some racing. He looked at the dates – all were between August and November 1917. The front pages gave reports of the Battle of Passchendaele in Belgium, one newspaper, however, was folded to the racing news. Perry scanned the page – it gave the result of that year’s St Leger and on seeing the name Gay Crusader, he was reminded of that great horse’s Triple Crown victories.

When later, he tossed the paper back onto the table, he caught sight at the foot of the wicker chair, what looked like a ladies prayer book.

It was, and inside the front cover, he read the inscription – “To Rosemary, with fondest love, Roland.”

“Strange,” he thought, “Perhaps he never gave it to her? Unless, that is, she sent it back!”

Finally, carefully folded into the back of the prayer book, he found a cutting from the local paper, telling of the bravery at Passchendaele of Lieutenant Roland Henderson-Bell.

When Father Green and Emily did their big loft clear-out, they vacuumed up all the cobwebs and dead insects and took down the tatty curtains and rolls of carpet. Lastly, it came to throwing out the Lieutenant’s card table and wicker chair. Still haunted by his memory, Perry deliberated with mixed feelings. Nevertheless, it was Emily who insisted, “The past is past Father, let’s now have a nice clean loft.”

So, as usual, in household matters, Emily had her way and everything was taken to the local waste disposal.

Returning from the tip, Father Perry was forestalled outside his house by a very old man.

“I saw you throwing out the last of Roland’s furniture,” he said inquisitively.

“You knew him?” replied Perry, stunned.

“Oh yeah, we all knew him round here years ago. Everybody gave him money you see; after all, he was so horribly wounded.

Mind you, that was before we realised he was gambling everything away on the horses. I was only a small boy at the time,” he said reminiscing, “but my Mum and Dad were very angry when they found out.”

“That said,” he continued, “I always had a soft spot for him – he used to call me little Tommy Atkins and on one occasion he showed me his medals and his officer’s revolver.”

“Sadly, what finished him was when his lady friend broke up with him. Soon after that, he died, suddenly like.”

“I shouldn’t be telling this to you Father,” he said, lowering his voice, “but I heard say she lost a child – whose, I couldn’t say. But you shouldn’t listen to rumours, should you?”

Father Green, however, felt compelled to keep the ladies prayer book and later that month, invited little Tommy Atkins to attend a belated Mass at St Joseph’s for Lieutenant Roland Henderson-Bell and his fiancé, Rosemary.

Very few attended, but Emily and the old man went along and sat near the front, where they saw Father Green put Rosemary’s prayer book on a corner of the altar. The Mass progressed through the usual rituals and concluded with the final blessing.

Afterwards, outside the church, while Father Green was conversing with his parishioners, he suddenly remembered he had left Rosemary’s prayer book on the altar. Excusing himself he hurried back through the empty church – it had gone.

For a moment or two, he felt confused, until believing that Emily must have picked it up. Then, while still a little unsure, he heard the scraping of a chair in the darkened Lady Chapel. Peering through the shadows, he could just make out the veiled outline of a young woman holding the hand of a child in school uniform. With caution, he slowly moved towards the figures, already knowing it was useless, as they became fainter and fainter until, on setting foot inside the Lady Chapel, he was just in time to catch a glimpse of the little girl turning and waving goodbye.

Father Green never told anyone of his experience and despite all his efforts, he was unable to recover Rosemary’s prayer book.

For more racing history see Michael’s Books for Sale.

Father Perry looked out on the paddock at Cheltenham; it was Thursday, March 18, 1982 – Gold Cup day. The answers as to how he had got there and what the repercussions would be, he preferred not to think about, at least until after the Gold Cup.

Father Perry looked out on the paddock at Cheltenham; it was Thursday, March 18, 1982 – Gold Cup day. The answers as to how he had got there and what the repercussions would be, he preferred not to think about, at least until after the Gold Cup.