The Marquis of Hastings scoops the Pocket Venus, alas!

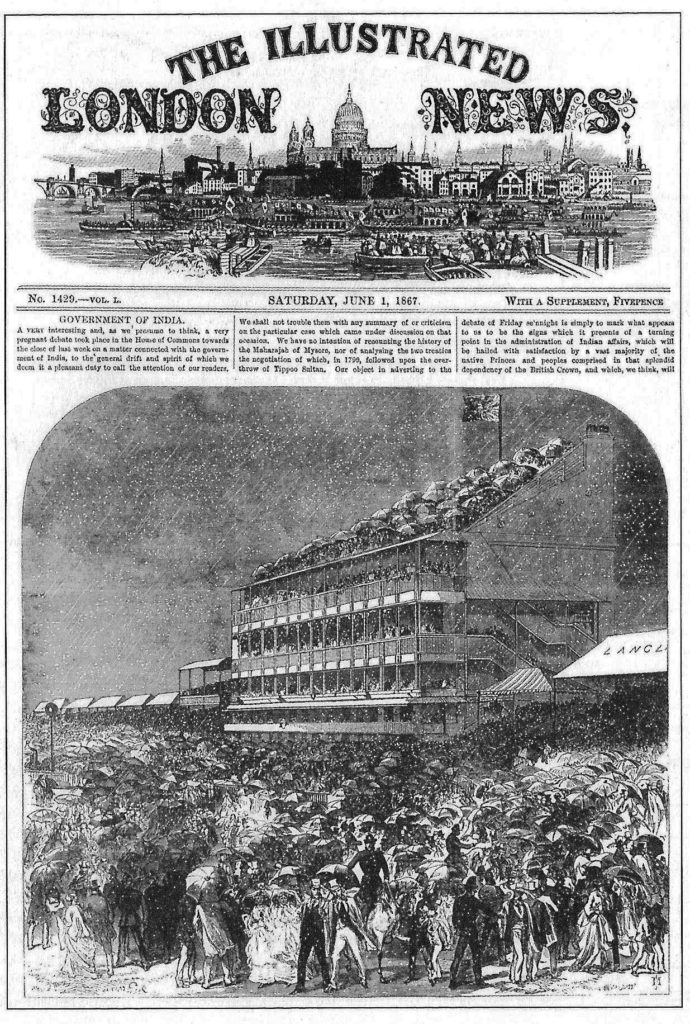

On Derby Day 1867, London society’s most romantic drama was played out before 300,000 racegoers on Epsom Downs. Surrounded by intrigue and scandal, the Marquis of Hastings and Mr Henry Chaplin had vied for the love of the season’s beauty, Lady Florence Paget, known in society as “The Pocket Venus”.

Both men had wealth, good looks and charm. However, each were tainted by the ‘win at all costs’ passion of a reckless gambler.

Both men had wealth, good looks and charm. However, each were tainted by the ‘win at all costs’ passion of a reckless gambler.

The story begins at Mr Blenkiron’s sale of Middle Park Stud yearlings at Eltham, Surrey, on Saturday, 17 June 1865, where the rivalry between the feckless Marquis of Hastings and Henry Chaplin took a twist from which one of them would never recover.

“Lot 27, a chestnut colt by Newminster out of Seclusion…” A small but good-looking, dark chestnut yearling entered the sales ring. Harry Hastings and Henry Chaplin, standing on opposite sides of the ring, watched the bidding rise in 50’s. Newminster, a St Leger winner, had already sired three Classic winners, including Derby winner Musjid, and his stock were commanding good prices. Harry Hastings held the bid at 850 guineas until Chaplin came in at 900. One more bid each then Hermit was knocked down to Henry Chaplin at 1,000 guineas.

The Sale continued … “Lot 28, a chestnut colt by Dundee out of Shot…”, was sold to Mr Merry, also for 1,000 guineas. Coincidentally, this yearling, later named Marksman, was to run second to Hermit in the Derby.

Henry Chaplin was the eldest son of the Reverend Henry Chaplin,Vicar of Ryhall in Rutlandshire. When only 19 he inherited the estate of Blankney in Lincolnshire from his uncle Mr Charles Chaplin. He went to Christ Church, Oxford in January 1859 and was given the nickname “Magnifico” on account of his grand life style. A year later he took the Prince of Wales “under his wing” and, before Chaplin left in December 1860, he had “kept an eye” on a shy and nervous Harry Hastings for a term.

In 1864, Chaplin became engaged to the beautiful Lady Florence Paget, youngest daughter of the Marquess of Anglesey. The announcement received extensive coverage in The Morning Post and The Times, while according to society magazines, Florence was “the rage of the park, the ballroom, the opera and the croquet lawn.”

In 1864, Chaplin became engaged to the beautiful Lady Florence Paget, youngest daughter of the Marquess of Anglesey. The announcement received extensive coverage in The Morning Post and The Times, while according to society magazines, Florence was “the rage of the park, the ballroom, the opera and the croquet lawn.”

Ironically, before the engagement, Harry Hastings had also courted Lady Florence, but, the characters of the two men could not have been more different. Henry Chaplin was a respected figure of the establishment; masculine, handsome, kind and generous. Harry Hastings, on the other hand, had all the hallmarks of a selfish rake. Even so, his air of “little boy lost” appealed to Florence’s strong mother instincts and, whereas Harry needed her, Chaplin showed that he could be self sufficient. Previously, when rumours of their engagement were circulating, he had gone off on a big game expedition in India, leaving Hastings to escort her through the social scene.

After the engagement, Chaplin, proud to have scooped “The Pocket Venus”, generously included Hastings in their intimate circle. Poignantly, on the evening of Friday, 15 July 1864, from a box at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, the three of them listened to the famous soprano Adelina Patti’s last night performance of Gounod’s “Faust.”

The following morning, Lady Florence tried on her newly delivered wedding dress for what everyone believed would be “The Wedding of the Year.” Then, at 10 a.m., she drove alone, in her father’s brougham from the St George’s Hotel in Albemarle Street to the Vere Street entrance of the fashionable store, Marshall and Snelgrove. Walking through the store to the door in Oxford Street, she was met by Lord Hastings. The couple then drove off to St George’s Church, Hanover Square, Euston, where she married Harry and became the Marchioness of Hastings. No members of her family were present. The bride was given away by Hastings’s friend Freddy Granville and at the reception, held at the Granvilles’ lodgings in St James’s Place, Lady Florence found a quiet room to write the following heartfelt apology to Henry Chaplin.

Saturday, July 1864

HARRY – To you whom I have injured more deeply than any one, I hardly know how to address myself. Believe me, the task is most painful and one I shrink from. Would to God I had had moral courage to open my heart to you sooner, but I could not bring myself to do so. However, now the truth must be told. Nothing in the world can ever excuse my conduct. I have treated you too infamously, but I sincerely trust the knowledge of my unworthiness will help you to bear the bitter blow I am about to inflict on you.

I know I ought never to have accepted you at all, and I also know I never could have made you happy. You must have seen ever since the beginning of our engagement how very little I really returned all your devotion to me. I assure you I have struggled hard against the feeling, but all to no purpose. There is not a man in the world I have a greater regard and respect for than yourself, but I do not love you in the way a woman ought to love her husband, and I am perfectly certain if I had married you, I should have rendered not only my life miserable, but your own also.

And now we are eternally separated, for by the time you receive this I shall be the wife of Lord Hastings. I dare not ask for your forgiveness. I feel I have injured you far too deeply for that. All I can do now is to implore you to go and forget me. You said one night here, a woman who ran away was not worth thinking or caring about, so I pray that the blow may fall less severely on you than it might have done. May God bless you, and may you soon find some one far more worthy of becoming your wife than I should ever have been.

Yrs.

FLORENCE

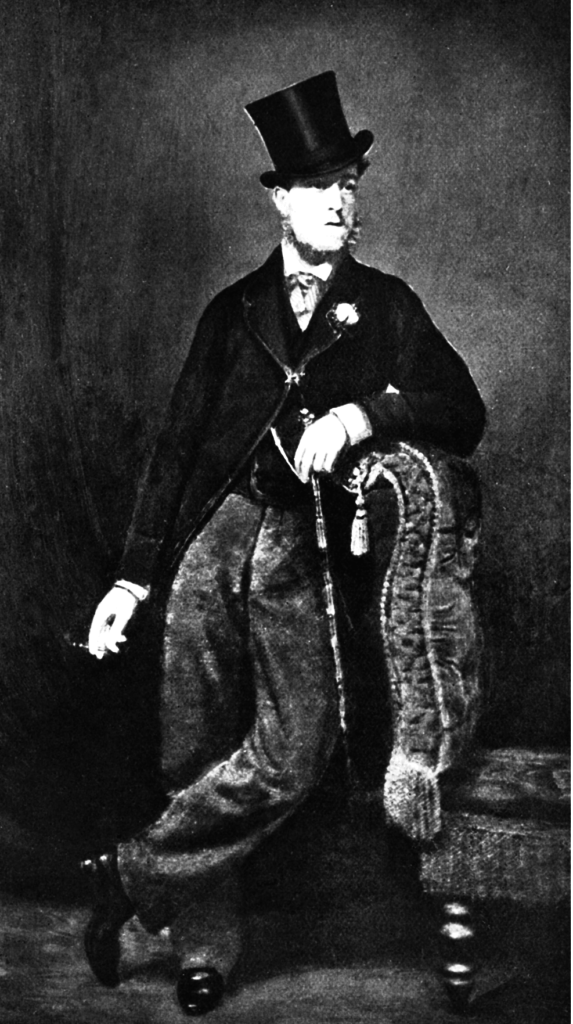

Henry Plantagenet, 4th and last Marquess of Hastings, was the classic Victorian example of a young man with plenty of money and little experience on the Turf. Sadly, Harry was less than two years old when his father died. And this, coupled with the sudden death of his elder brother seven years later, left the young Harry with a vast inheritance.

Henry Plantagenet, 4th and last Marquess of Hastings, was the classic Victorian example of a young man with plenty of money and little experience on the Turf. Sadly, Harry was less than two years old when his father died. And this, coupled with the sudden death of his elder brother seven years later, left the young Harry with a vast inheritance.

Generous and charming with friends, he treated his employees badly and, when Master of the Quorn, he would often quit the hunt at midday for a session of cards or dice.

And so the eternal triangle was assembled. After being deserted by Lady Florence, Henry Chaplin threw himself fervently into racing, buying horses “as though he were drunk and backing them as if he were mad!” He had, however, an ace up his sleeve. That ace was Hermit.

Under the management of Captain Machell, Hermit was trained at Newmarket by Bloss. And, as time passed, it became obvious that an exciting bargain was in prospect.

First tried over four furlongs on Bury Hill, with the useful filly, Problem, Hermit beat her by two lengths, giving her 35lb.Two months later on 20 February, Problem won the Brocklesby Stakes at Lincoln from a big field, and followed it up by beating Hippia, a future Oaks winner, at Northampton. Captain Machell then hurried to London and backed Hermit to win the Derby for a large sum of money at odds of 20-1.

Hermit made his racecourse debut at Newmarket in the spring of 1866 where, in the race before the Two Thousand Guineas, he was beaten three-quarters of a length by Cellina over four furlongs. The Machell camp were not downhearted however; Cellina had a previous victory and her experience had told. Three weeks later at Bath, Hermit reversed the placings with Cellina, winning by a neck.

In the Woodcote Stakes at Epsom, Hermit came up against Achievement, a brilliant filly who went on to win the One Thousand Guineas and St Leger the following year. She beat him by three lengths in a scintillating performance. Later, however, Hermit progressed to win at Ascot and then twice at Stockbridge, beating Vauban on both occasions.

Vauban had won seven of his 15 races as a two-year-old and the following season won the Two Thousand Guineas by two lengths from Hermit’s stable companion Knight of the Garter, with Marksman a head away third.

With the Derby approaching, Captain Machell and Henry Chaplin now had a direct line to Vauban and Marksman through Knight of the Garter. A trial was arranged with Hermit to concede 10lb to Knight of the Garter over a mile. Hermit proved his superiority and the stable’s ante-post vouchers looked gilt-edged.

Soon after, plans were made for a further trial, this to be run a week before the Derby over one and a half miles, with the four year-old Rama, a Doncaster Cup winner, conceding 14lb. Captain Machell, however, leaving nothing to chance, insisted on both horses having a rough gallop on the Monday, to allot the trial weights more accurately.

Hermit, ridden by Henry Custance, after travelling exceptionally well, gave a tremendous cough and stumbled. The colt’s nose and mouth were cleaned up and, to keep the incident a secret, Custance took him home “the back way”. A thorough examination followed, when it was discovered that Hermit had burst a blood vessel in his nostril.

Hermit’s chance in the Derby now looked remote, yet despite Chaplin wanting to scratch Hermit, Captain Machell refused to give up hope and persuaded him to delay his decision. When the news of Hermit’s gallop spread, Custance was approached by Mr Pryor to ride his fancied entry, The Rake. Accordingly, Chaplin, not wishing to deprive his jockey the chance of winning the Derby, wrote to Pryor, releasing him.

Almost immediately after, came the news that The Rake had also broken a blood-vessel in his final preparation. In a further twist, Machell, in the light of Hermit’s encouraging response to treatment, suggested to Chaplin he re-engage Custance. Pryor, however, remained set on running The Rake and refused to release him. The case then went to the Stewards, who judged that Chaplin’s letter to Pryor constituted a release and gave Prior the decision, adding, that as both horses had broken blood-vessels, in all fairness he should relinquish his claim. This, Pryor refused to do, compelling Custance, to endure the eventual irony.

To rub salt into Custance’s wound, the day before the Derby he witnessed Bloss’s horses do their final work at Epsom. Custance recalls in his Riding Recollections, “Hermit was sent to canter a mile on the Derby course. This was the first canter he had done since he had broken his blood-vessel, nine days previously. Hermit used to pull a bit, and he got the best of the boy coming round Tattenham Corner, fairly ran away with him, and, the ground being as hard as iron, he bounded over it like a cricket ball. Chris Fenning, who was standing with me, said: ‘“Be jabbers, I never saw a horse like that! He will win the Derby.”’

Captain Machell, meantime, determined to keep Hermit’s blood cool, gave him very little hay and covered him with only a light blanket. Most of his work was downhill and, on the Saturday, before the Derby, Hermit did six one-mile canters the reverse way of the Rowley Mile.

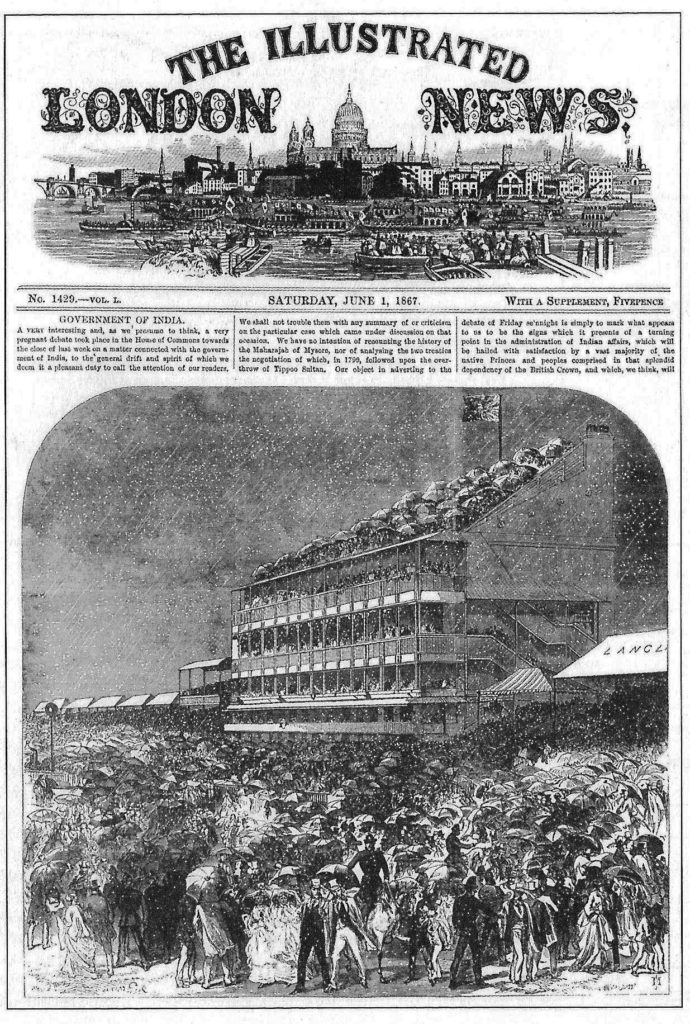

The snowstorm before the Derby

Derby Day arrived with snow showers throughout the day, allowing fate to give our story yet another twist – for this would surely cool Hermit’s blood. His appearance in the paddock, however, was far from convincing. Baily’s Magazine reported, “One would say, ‘Ah poor Hermit!’ and then passed by on the other side; and another would turn up his nose as if at tainted air, and exclaim, ‘Pah! ‘a corpse!’ and there was no good Samaritan to say one good word in his favour.”

To illustrate the intensity of feeling the race brought, a first- hand account of the race from Amphion of Baily’s Magazine follows:

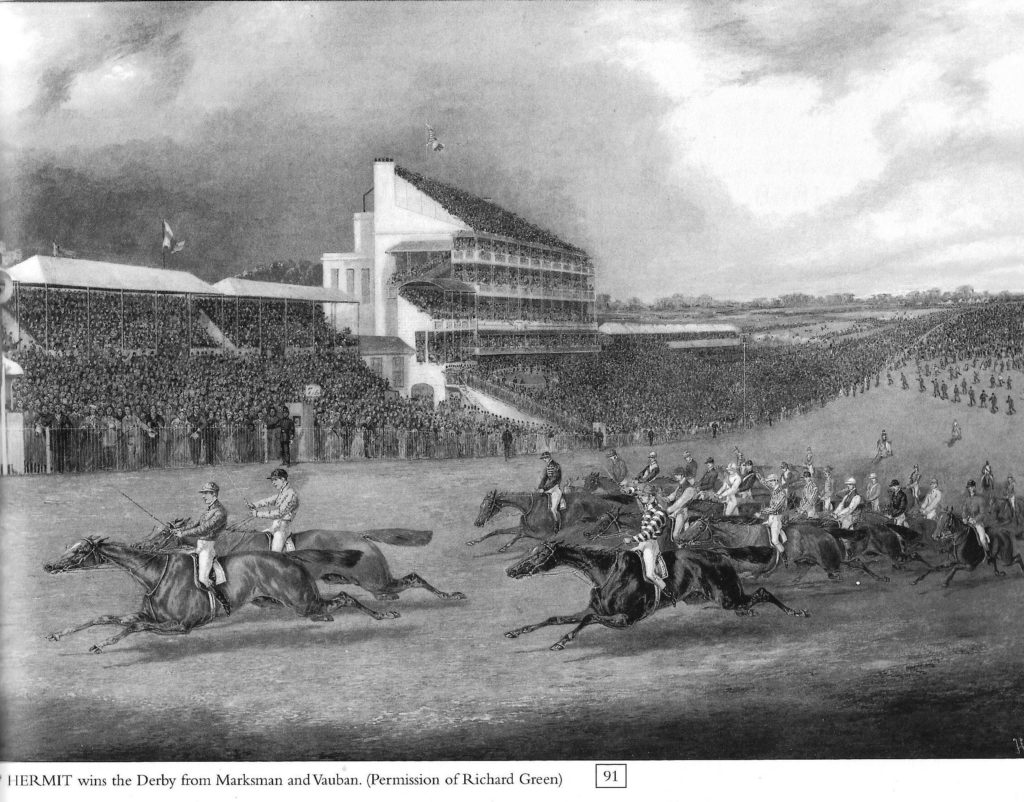

“Just as the horses reached the post, the welcome sun shot through the clouds a momentary beam, as if in honour of the contest, upon the issue of which the minds of that vast multitude were hanging in excited suspense. Gazing over that sea of heads in front of us, the eye wandered up the serried ranks which lined the course far and away past Tattenham Corner to the beginning of the furzes at the top of the hill. Waiting for the hoarse roar which drowns the last notes of the ‘warning bell’ have you, reader, ever analyzed your feelings at that moment when that bright bevy of coloured specks is dimly seen over the black mass at the starting-post ‘now advancing now retreating,’ now breaking away, now turning back, or waiting for some companion who declines to join the melee?

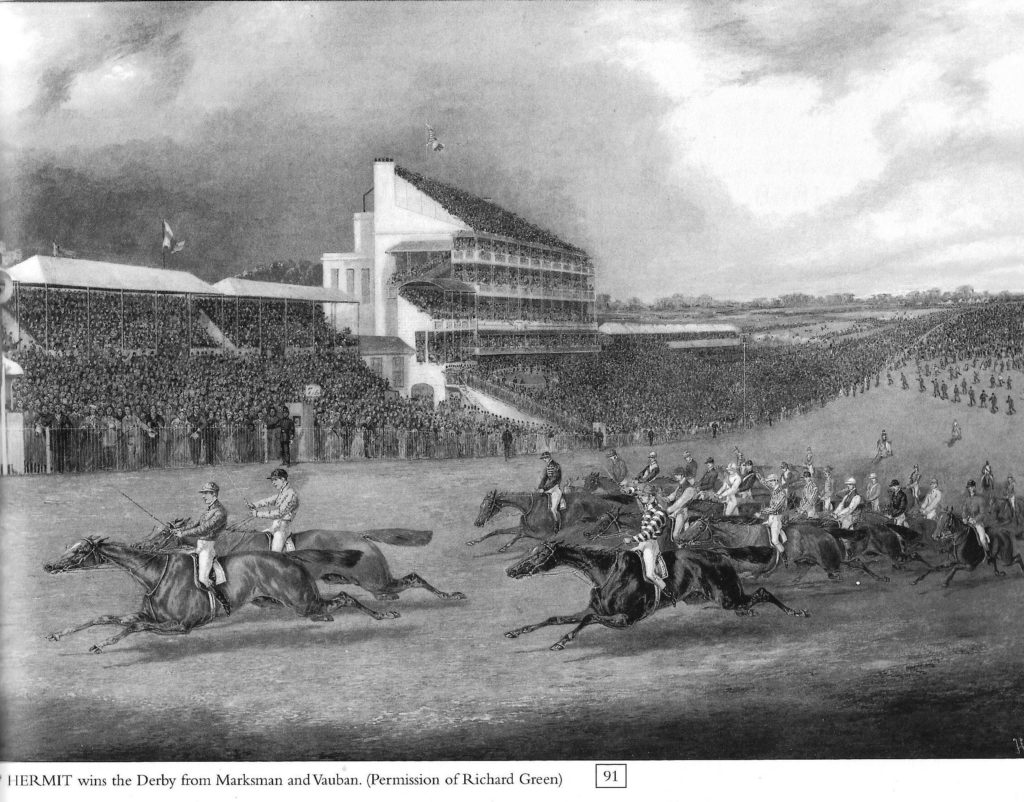

Who has not felt that half-pleasurable, half-painful sensation, when the mind hangs between hope and fear, the feeling that upon this ‘maddest, merriest day’ the issue of that contest will be decided which has cost us so much thought, so much study, such long anxious deliberation. How do we yearn for, yet fear the end; how slowly passes the time until the long rainbow line is stretched in marshalled order across the course. Then as for the last time we strive to anticipate, though by a few minutes only, the verdict of the judge comes the roar of thousands, like the sound of many waters, and the Derby cloud flies up the slope, and are lost sight of for a few seconds behind the hill. Here they are at last, Vauban with a slight lead then Marksman, Van Amburgh, and The Palmer close together, with Hermit at their heels: a shout as Palmer has cried enough, and Hermit creeps up to the leaders; then loudly screams the Ring as Fordham begins to ride the favourite, and his backers groan responsive: at the distance Marksman leads until the stand is reachcd, and now for the death-struggle. Marksman, ridden with the most consummate judgment, still holds his own; but a touch may upset him, while Daley calls vigorously on Hermit, who responds most gamely, and finally defeats Marksman by a neck; the favourite a bad third, Wild Moor a respectful fourth, then Van Amburgh, Owain Glcndwr, and Tynedale, and the ruck. Middle Park forever!”

Immediately after, Captain Machell was a rich man, having won over £60,000 (over £4 million today), for his patience and determination, while the stable won a further £90,000 (over £6 million today).

Immediately after, Captain Machell was a rich man, having won over £60,000 (over £4 million today), for his patience and determination, while the stable won a further £90,000 (over £6 million today).

Captain Machell was 29 years old at the time of “Hermit’s Derby”. He joined the army in 1855 and reached the rank of Captain in 1862, but the following year, he sensationally resigned his commission when refused permission to see the St Leger. An accomplished athlete, he won many wagers for jumping from the floor on to a mantelpiece and, for jumping over a billiard table. In 1864 he moved to Newmarket and after a successful start as an owner, he proved an exceptional judge of jumpers, owning three Grand National winners: Disturbance (1873), Reugny (1874) and Regal (1876). As manager for Henry Chaplin, he showed great patience and ingenuity to win the Derby with Hermit, and later, he assisted Colonel Harry McCalmont to win the 1893 Triple Crown with Isinglass. At his height, Captain Machell was one of the most powerful and most knowledgeable men in racing and it was he who advised Henry Chaplin to buy Hermit at the Middle Park Sales.

Hermit’s Derby pilot, John Daley (1846-c.1890), was the son of a Newmarket trainer. He had his first race when only 11 years old, weighing in at 3st 10lb. At Royal Ascot in 1860, he rode four winners, including the Coronation Stakes on Allington. In 1867, Captain Machell booked Daley to ride Hermit in the Derby only days before the race and, with his usual flair, promised him £100 for the ride, a further £100 if placed and £3,000 if he won it, which he did. Two days later, Daley won the Oaks on Hippia for Baron Meyer de Rothschild at odds of 11-1. But thereafter, he struggled to do the Classic weight of 8st 10lb, although he did ride Macgregor to win 1870 Two Thousand Guineas, albeit at 1lb overweight.

While Hermit’s victory had brought riches to Captain Machell and Henry Chaplin, to the 4th Marquess of Hastings he had brought disaster and debts of £120,000 (over £8 million today). Hastings had laid Hermit for the Derby at generous prices to the owner’s stable for over a year, in a vendetta against Henry Chaplin. At a party on the evening of the Derby, Hastings vowed he would make the Ring settle his debts for him, but the defeat of Achievement in the Oaks “turned the screw a little tighter”.

Harry Hastings arrived at Tattersalls on the Monday, having fully mortgaged his estates with Padwick the moneylender and having accepted Henry Chaplin’s proposal giving him time to pay. He was cheered to the man. In a gambler’s world, Hastings would not accept defeat; after all, his Lady Elizabeth was favourite for next year’s Derby!

The year passed with mixed fortunes. Another Derby Day dawned and Harry had summoned enough credit for one enormous plunge on Lady Elizabeth. She was backed at all rates down to 7-4 favourite, but was hopelessly beaten. Harry had her out for the Oaks two days later, but she disappointed again. Hastings was now totally destroyed. After a cruise upon his yacht, off the coast of Norway, he returned home to Donnington to die at the age of 26.

The cause of death was given as Bright’s disease, brought about by excessive eating, drinking and worry. Finally, upon his deathbed, he whispered, “Hermit’s Derby broke my heart, but I didn’t show it, did I?”

Florence married again, 18 months after Harry’s death. Her overtures to Chaplin had fallen on stony ground, but she still needed to be part of the social scene. As before, her second marriage came as a complete surprise to her friends, for she married a man who was not only seven years younger than her, but another highflying gambler of the Turf. Tall, slim and charming, his name was George Chetwynd. And although popular with some, the Honourable George Lambton recalled, “He was more talked of, more envied and in some quarters more disliked than any man of the fashionable world.”

Even so, Florence had four children by him – one son and three daughters. When she died, aged 64, in 1907, there were many letters of condolence and a great number of wreaths, but not one from Henry Chaplin.

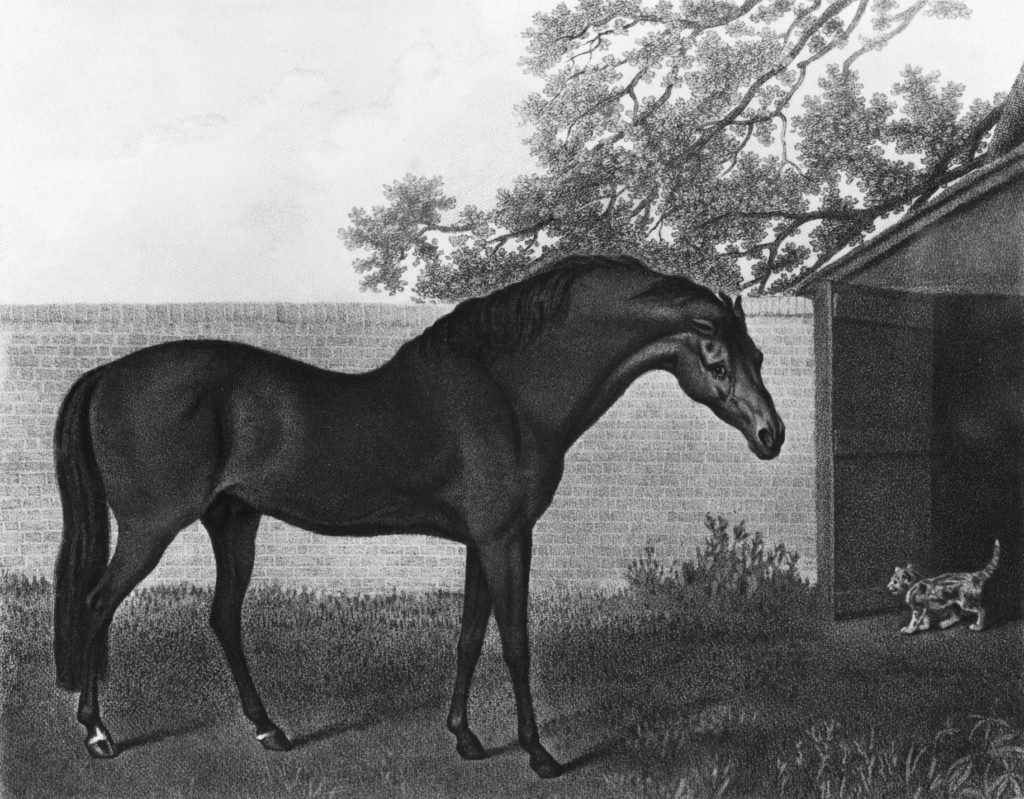

Hermit, of course, had outlived Harry Hastings and soon after his Derby victory, won twice at Royal Ascot, including the St James’s Palace Stakes. Later, he finished second to Achievement in both the St Leger and the Doncaster Cup but, save for a small sweepstake on the same Doncaster Cup day, he never won again in 13 outings.

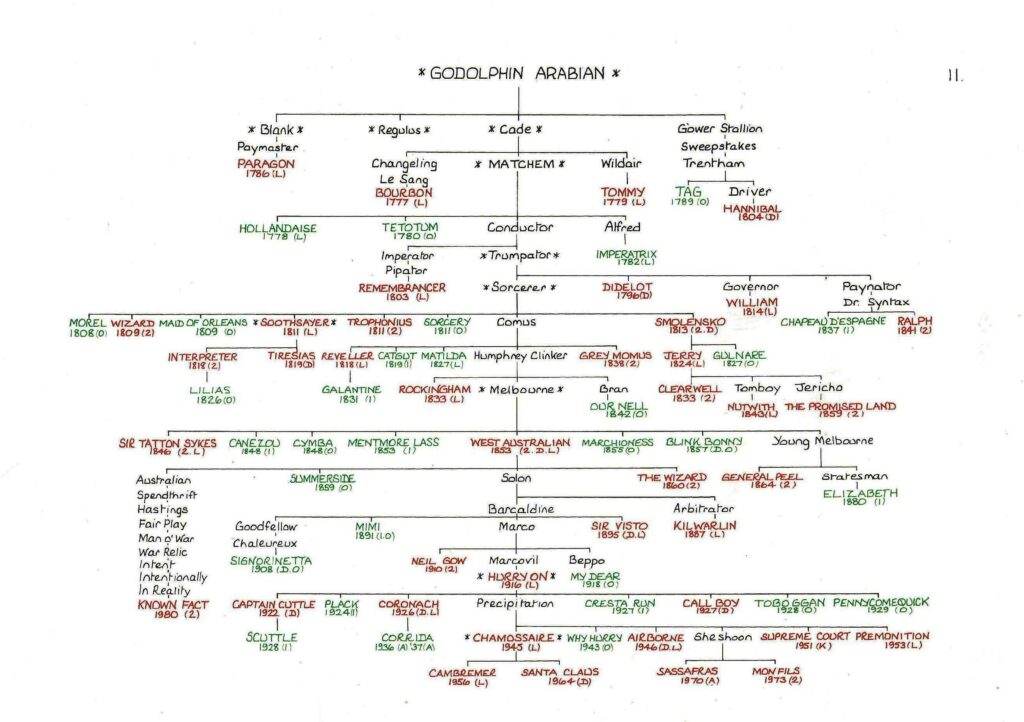

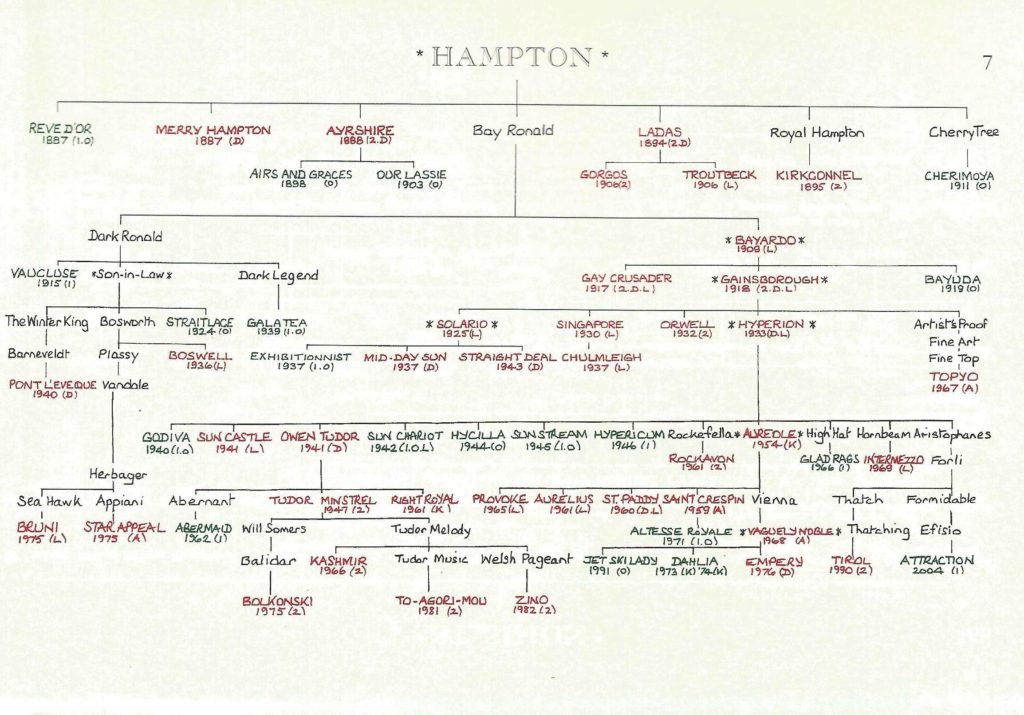

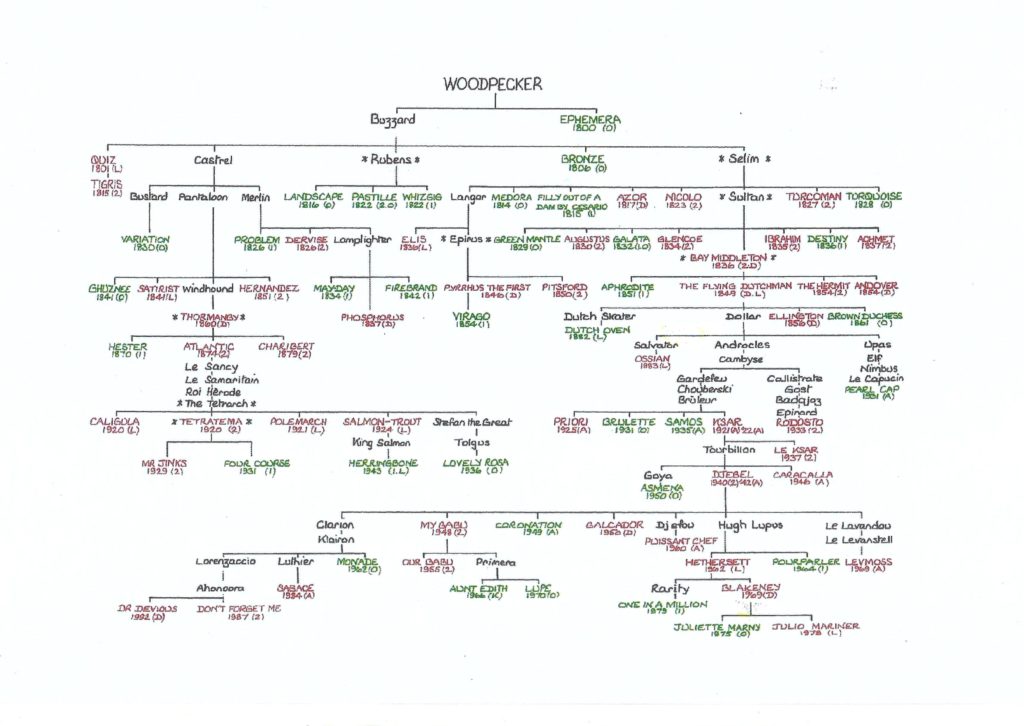

Thereafter, Hermit went to stud at Blankney for the modest fee of 20 guineas, but, his success surpassed all anticipation. He was Champion Sire seven consecutive years from 1880 to 1886, getting the winners of seven Classic races, including the Derby winners Shotover (1882) and St Blaise (1883), by which time his fee had risen to 300 guineas. Living to the age of 26, Hermit died on 29 April 1890.

Henry Chaplin, meanwhile, devoted much of his time to politics. A typical Tory squire, he became the Minister of Agriculture and was raised to the peerage in 1916. He died in 1923, and to the end of his life, he openly admitted that Hermit was the best friend he ever had.

For more history from Michael click on the link below

http://Michael’s Books for Sale

To see Michael’s interviews go to the foot of About Michael

Sir Charles Francis Noel Murless (1910-1987), rode first as an amateur and then as a professional jump jockey for Martin Hartigan at Weyhill. Thereafter, he worked as assistant trainer to Hubert Hartigan (Martin’s brother), in Ireland. From 1935, Murless trained successfully from Hambleton, near Thirsk, albeit with horses of limited ability. However, on the retirement of Fred Darling at the close of the 1947 Flat season, Murless took over Beckhampton, retaining the association with Gordon Richards. The following year he was Champion Trainer for the first time and topped the lists a further eight times in his career.

Sir Charles Francis Noel Murless (1910-1987), rode first as an amateur and then as a professional jump jockey for Martin Hartigan at Weyhill. Thereafter, he worked as assistant trainer to Hubert Hartigan (Martin’s brother), in Ireland. From 1935, Murless trained successfully from Hambleton, near Thirsk, albeit with horses of limited ability. However, on the retirement of Fred Darling at the close of the 1947 Flat season, Murless took over Beckhampton, retaining the association with Gordon Richards. The following year he was Champion Trainer for the first time and topped the lists a further eight times in his career. William Richard ‘Dick’ Hern (1921-2002), was born in Somerset and, after serving in the North Irish Horse in World War II, held the position of coach to the British gold-medal winning equestrian team in the 1948 Olympics. In 1957, having worked as assistant trainer to Michael Pope, he took over the Lagrange Stable at Newmarket.

William Richard ‘Dick’ Hern (1921-2002), was born in Somerset and, after serving in the North Irish Horse in World War II, held the position of coach to the British gold-medal winning equestrian team in the 1948 Olympics. In 1957, having worked as assistant trainer to Michael Pope, he took over the Lagrange Stable at Newmarket. Vincent O’Brien (1917-2009), is widely regarded as the greatest trainer of the 20th century, both on the Flat and over the jumps. His 16 British Classic victories included, two winners of the Oaks – Long Look (1965) and Valoris (1966), and six winners of the Derby, notably Sir Ivor (1968) and Nijinsky (1970 Triple Crown). Over the jumps, he trained the winners of three consecutive Grand Nationals between 1953 and 1955 – Early Mist, Royal Tan and Quare Times – four Cheltenham Gold Cups and three Champion Hurdles.

Vincent O’Brien (1917-2009), is widely regarded as the greatest trainer of the 20th century, both on the Flat and over the jumps. His 16 British Classic victories included, two winners of the Oaks – Long Look (1965) and Valoris (1966), and six winners of the Derby, notably Sir Ivor (1968) and Nijinsky (1970 Triple Crown). Over the jumps, he trained the winners of three consecutive Grand Nationals between 1953 and 1955 – Early Mist, Royal Tan and Quare Times – four Cheltenham Gold Cups and three Champion Hurdles.

Both men had wealth, good looks and charm. However, each were tainted by the ‘win at all costs’ passion of a reckless gambler.

Both men had wealth, good looks and charm. However, each were tainted by the ‘win at all costs’ passion of a reckless gambler. In 1864, Chaplin became engaged to the beautiful Lady Florence Paget, youngest daughter of the Marquess of Anglesey. The announcement received extensive coverage in The Morning Post and The Times, while according to society magazines, Florence was “the rage of the park, the ballroom, the opera and the croquet lawn.”

In 1864, Chaplin became engaged to the beautiful Lady Florence Paget, youngest daughter of the Marquess of Anglesey. The announcement received extensive coverage in The Morning Post and The Times, while according to society magazines, Florence was “the rage of the park, the ballroom, the opera and the croquet lawn.” Henry Plantagenet, 4th and last Marquess of Hastings, was the classic Victorian example of a young man with plenty of money and little experience on the Turf. Sadly, Harry was less than two years old when his father died. And this, coupled with the sudden death of his elder brother seven years later, left the young Harry with a vast inheritance.

Henry Plantagenet, 4th and last Marquess of Hastings, was the classic Victorian example of a young man with plenty of money and little experience on the Turf. Sadly, Harry was less than two years old when his father died. And this, coupled with the sudden death of his elder brother seven years later, left the young Harry with a vast inheritance.

Immediately after, Captain Machell was a rich man, having won over £60,000 (over £4 million today), for his patience and determination, while the stable won a further £90,000 (over £6 million today).

Immediately after, Captain Machell was a rich man, having won over £60,000 (over £4 million today), for his patience and determination, while the stable won a further £90,000 (over £6 million today).