The Festival of Britain Stakes

With the Investec Derby, Oaks and Royal Ascot behind us, I’d like to tell you a short story about my train trip to the first running of Ascot’s King George. Billed as the Festival of Britain Stakes, with more prizemoney than the Derby, it was heralded as the race of the year.

Amid the noise and excitement, a crowded train pulled into Clapham Junction; it was one of many that day leaving for Ascot races. This was Festival of Britain year 1951, and racing’s contribution to the festivities was a new race – the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Festival of Britain Stakes. Everyone seemed to be talking about it and everyone wanted to be there. On top of that, it was one of those days of characters and mysteries that were to sink sublimely into my youthful memory. Clambering aboard, I squeezed into a train filled with cigarette smoke and swaying bodies.

“There’s room for a nipper over here,” a large lady beckoned – I squeezed in. Her bright blue turban and flowered print dress contrasted dramatically with the sombre utility suits of the four men facing me. Directly opposite was a pale-faced man, fortyish, with dark crinkled hair, who I later learned was Mori. Turning to his neighbour, who looked ex-RAF and sported a ginger moustache, he said, “I’ve got a jacket at home that will fit you perfectly.”

“Sounds good,” said the moustache. “How much do you want for it?”

Mori paused, “If it fits you, it’s yours, free, gratis,” adding, “when you’ve had a winner you can pay me for it.”

“You see John’s jacket,” he continued, turning to the battered trilby on his right, “that’s one of mine. How long have you had that John?”

John frowned and took a sharp intake of breath.

“Must be 25 years now.”

“You see – quality,” beamed Mori. “Your brother’s got a similar jacket hasn’t he John?”

“Yes, he has sometimes.”

“What do you mean sometimes,” retorted Mori, now fully in command of the quartet.

“Well, he has it when I let him borrow it,” said John.

“You and your brother are a mystery to me,” continued Mori.

“Tell me, how is it you’re 50 and your twin brother says he’s nearly 60?”

“Ah,” said John, “He lies about his age!”

At this point, Reggie, their fourth member – egg-stained tie, and pebble glasses – looked up from his window seat, where he had been engrossed in The Sporting Life.

“Er John, isn’t that the jacket that your Mum wanted to bury your Dad in?”

Richmond – Twickenham – Feltham, the train was now heaving and a further gaggle of passengers stood between the two rows of seats in our carriage, temporarily depriving me of this surreal banter. And it was not until two of them found room in the corridor, that I tuned in again to the moustache opposite.

“Flat on the floor I was, threatened with a shooter – then they blew the safe – I couldn’t stop shaking, but when they opened it there was only a monkey inside.”

The blue turban chuckled and her fag-ash went all over my lap.

“Sorry darlin’,” she exclaimed, “but you gotta laugh, ain’t yer?” And she did, like a drain.

At Staines, two bottled beers got in, and after passing the Daily Herald to and fro, a Fairisle pullover enquired of Mori, “Er, mate, lend us a pen for a sec.”

“Sorry,” said Mori dismissively. Whereupon, the Fairisle bothered everyone in turn for something to write with.

Finally, the blue turban offered him a crayon, which she later told me she had used to draw stocking seams on the back of her legs. Meanwhile, it was obvious, even to me as a 15-year-old, that the two bottle beers were a con-act, supposedly marking in that day’s stable whispers. And sure enough, as soon as we were pulling into Ascot station, I heard the Fairisle say to the ginger moustache, “Five bob and I’ll mark yer card.”

Hastily grabbing my brown paper bag from the luggage rack, I didn’t look back to see if the fish was landed, as by now, I was being swept along the platform by the crowds that spilled out from every door on the train.

Down the underground tunnel and out into the light, we were met by all manner of tipsters, vendors and entertainers along the footpath to the racecourse. And it was not until I had reached my vantage point in the middle of the course that I stopped to unpack my lunch: two loose bananas, The Sporting Life, a bottle of Stout and, a pair of pyjama bottoms – I had grabbed the wrong bag! Always the opportunist, I managed to make use of the first three items, but I had to admit the fourth had me stumped. More importantly, who had got my mother’s Opera glasses and the cheese and pickle sandwiches she had so lovingly packed? My mind went back to the carriage; which of them was likely to take pyjamas to the races?

But now there were more important riddles to solve, as 18 two-year-olds went to post for the first, over the straight six furlongs. Soon after, Gordon Richards came back to tremendous cheering on the favourite, Olympic. Half-an-hour later, Scobie Breasley did favourite backers another good turn, when the filly, Verse, won in a photo finish.

Moving over to a spot opposite the paddock, I watched the best horses in Europe filter out on to the course, for what was to be the first ‘King George’. Its prize of £25,000 was the richest ever for a British race.

The favourite was the Derby winner Arctic Prince, while the opposition included Tantieme (Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe), Scratch (St Leger), Supreme Court (King Edward VII), Belle of All (1,000 Guineas), Ki Ming (2,000 Guineas), Sir Winston Churchill’s grey, Colonist, and the temperamental Zucchero with the 15 year-old Lester Piggott aboard.

Nineteen runners went to post before a crowd reported to be more than 100,000.

I had taken an array of bets from my school-mates on the race, including two doubles running-on from Olympic to the long-shots Belle of All and Ki Ming, but refusing to hedge-off, I stood my ground.

Without a public commentary, or my Mum’s opera glasses, it was hard to know what was going on, but a tall man standing on a hillock nearby shouted out that Wilwyn and Belle of All were leading, and even I could see the grey, Colonist, up with the leaders. But along the home straight, two horses pulled away from the rest – the electric atmosphere and the tremendous roar from the crowd gave me the feeling of being in the middle of a great storm, although in reality it was a bright sunny day.

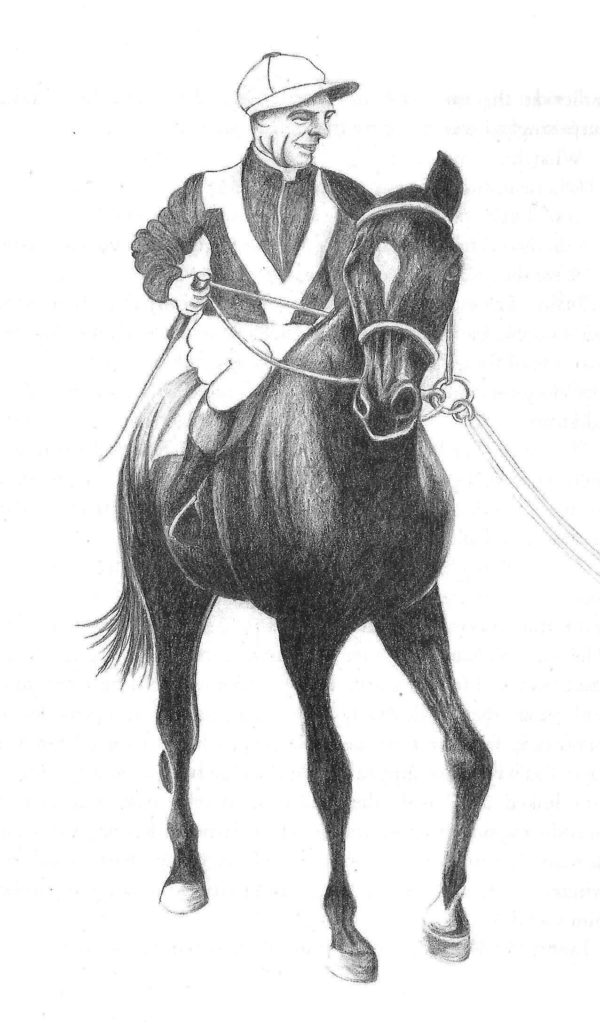

Finally, I could see Charlie Elliott in the colours of Supreme Court – scarlet with a white V – get the better of young Lester on Zucchero. Both horses broke the 30-year-old course record.

Having weathered the storm, I realised that no-one at school had backed Supreme Court, so, to celebrate I bought a jumbo ice-cream cone and washed it down with the bottle of stout. Nevertheless, still in the possession of an unwanted pair of pyjama bottoms and, without an immediate use for them, I decided to let them loose in the makeshift lavatories. On my way out, I saw a huddle of men gathered at the exit. Not the usual ‘Find the Lady’, but Banker! Suddenly, I was joined by the Fairisle pullover.

“Had any winners”, I piped up.

“Oh, hello titch, weren’t you on our train?”

“Yes,” I said, then pressing, “How are your tips going?”

“Oh, those,” he grinned, “just out to make a bob or two, you know.”

“Were they really stable whispers?” I persisted.

“Nah – just a couple of favourites and some my old Mum picked out – double-barrelled names with the same letter, you know, Fast Fox, that sort of thing,” he said with surprising candour.

Spilling out into the light, I was confronted by a cockney balloon salesman.

“The more yer blow, the bigger they grow,” he proclaimed. And then, as a small gathering of children surrounded him, he proceeded to make a series of giraffes, poodles and dachshunds from blowing and twisting balloons.

“One shilling for a giraffe,” he announced, “start your own zoo today.”

A further two races passed – Fast Fox 7-2 and Lancashire Lassie 13-2. The Fairisle’s Mum certainly knew a thing or two!

Drifting through the crowd and feeling a little thirsty, I went into the beer tent to try and get another bottle of stout, but after standing on tip-toe for five minutes in front of a bar, now five deep, I heard a voice behind me say: “You’ll be lucky, nipper.” It was the blue turban, who surprisingly had linked arms with the ginger moustache from our carriage, introducing him as Ralph and herself as Betty. Both seemed very jolly, as Ralph, having paid five-bob for the Fairisle’s tips, had backed three winners. Betty snuggled up to him and told me she was going to help him spend it.

Eventually, Ralph got to the front of the bar and ordered me a beer. Standing in a corner of the tent, Betty mused, “I brought a bottle of stout with me, but must have picked up the wrong bag – still the sandwiches came in handy.”

What could I say? I couldn’t ask her about my Mum’s opera glasses, or the subject of the pyjama bottoms would crop up. I didn’t feel equal to that discussion, so I kept quiet, but my mind ran riot with bizarre images of their employment.

After another round of drinks, courtesy of Ralph’s success, we dashed out to back the favourite in the last. Wanting to look big, I had a £1 on it, while Betty was urging Ralph to double his stakes. Inside the final furlong, the favourite Pares, and Red Linnet (the danger), were up-front going hammer and tongs. I confess I had to look away, but I could hear Betty screaming and then noisily kissing Ralph.

It had been a great day for all of us. We collected the cash and walked back to the Railway Station, where we met up again with Mori. He seemed a little quiet however, and declined the offer to accompany us to White City dogs. Ten minutes later, having talked about our varying degrees of success, we boarded the London train together.

Mori looked tired, and sank back into the corner seat. After a few minutes of staring blankly out of the window, he sighed and said,

“Life’s like a game of poker you know; most people are dealt a hand for life – I think mine was a pair of Jacks. Not great, but when the opposition is weak or they hesitate, you can pick up a few quid. Some good times, some bad and, if you like what you’re doing, even the bad times are good.”

We all nodded respectfully at his obscure soliloquy. I guessed that Mori was coming to terms with a very bad day.