A Tale of Two Cup Finals

This is a tale taken from my second book of short stories Born to Bet.

Uncle Charlie pulled his chair closer to the fire; the tale he told me seemed to come from the realms of fantasy, but he assured me it was true – it was of the events surrounding the 1923 F.A. Cup Final betweem Bolton Wanderers and West Ham United, the first at Wembley.

Arriving at the stadium early, Charlie and his brother Ernie were told the ground was full and the turnstiles closed. However, along with thousands of others, they made their way into the ground illegally – in their case, up a very tall drainpipe and over a wall.

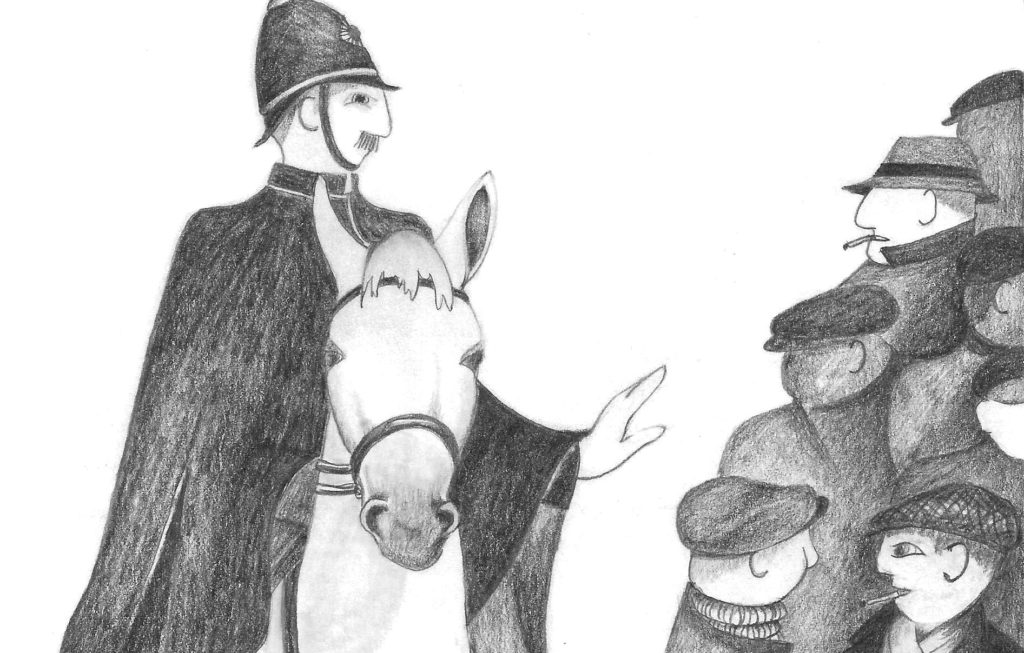

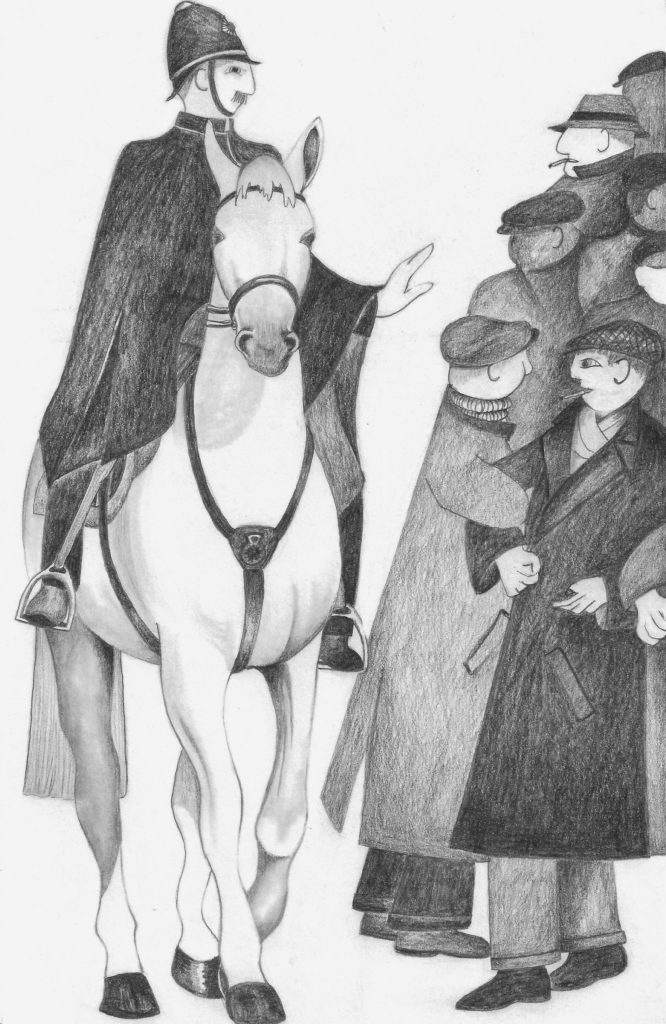

There was still an hour before kick-off, but when they got down the other side onto the terraces, they couldn’t move; 200,000 people the papers said, twice the ground capacity. Ernie had to get on Charlie’s shoulders to see what was going on; he said he couldn’t see the pitch for the weaving of heads, like bees swarming, but he could see, far away, a white horse.

The copper riding Billy, as the horse was called, went around telling everyone to link arms and push back. Forty minutes later, he and a squad of other coppers, some on horseback, had cleared the pitch, but only taking the spectators back to the touchlines. In the meantime, Charlie said it was murder on the terraces, and when the game eventually started, he and Ernie had to take turns on each other’s backs to watch the game.

Charlie took up the story:

“We missed seeing the first goal completely, but the papers said that David Jack hit the first for Bolton with such force that it knocked a bloke over standing behind the goal who, in turn, knocked over a whole row of spectators like skittles. And that wasn’t all. In the lead-up to the first goal, the West Ham right back, Tresadern I think it was, got trapped in the crowd after taking a throw-in, and while he was fighting his way back through the spectators, Bolton scored.”

At half-time the players were compelled to stay on the field, and around 10 minutes after the re-start, Bolton scored again. But what a to-do! Vizard of Bolton received a pass from a spectator standing on the touch-line, before centering the ball to Smith, who vollied it so hard into the net that it hit a spectator behind the goal and bounced out again. West Ham claimed it had hit the crossbar, but the referee gave the goal and Bolton won 2-0. What King George thought of it all I don’t know, but I bet it didn’t take him as long as us to get home – just before ten o’clock, my Mum said !

Charlie’s colourful description of the match buzzed around in my head for days, until one wet games period, when Bill Long, our Games Teacher and incidentally Captain of Woking Football Club, asked if anyone would like to talk about a sporting event they had seen. No-one put their hand up, so I bravely asked if I could relate my Uncle Charlie’s account of the first Wembley Cup Final. Long agreed. I said bravely, as having a stammer, B-B-Bolton and Wer-West Ham were not for me the easiest of teams to pronounce.

The events of the game produced outbursts of laughter from the class, with Long occasionally interrupting my flow with, “Is this true Church?” and “Are you making this up?” Well, I might have exaggerated the spectators collapsing like a row of dominoes, but I think my mates enjoyed it.

Two weeks later, there was a knock on our front door; it was Clarrie Jarman, a school-board inspector and the Secretary of Woking Football Club.

“Come inside Clarrie.”

Dad, a lifelong supporter of the club, welcomed him in, calling down the passage to my mother, “It’s Clarrie, Dorothy – put the kettle on.”

“No, no,” protested Clarrie, “I won’t stay long; it’s just that one of our Committee has returned his two Cup Final tickets and, I know it’s short notice, but I thought you and Michael would like to go.” He handed Dad an envelope.

“They’re not too expensive; three shillings (15p) each. It’s Manchester United and Blackpool on Saturday,” he added unnecessarily.

“By the way,” he told Stan, going to the door, “I hear young Michael gave a great account at school of your brothers’ visit to the ‘White Horse Cup Final’.”

Next day at school, I could think of nothing else, but fearing a jealous reaction, I decided not to tell anyone. Then, after the last lesson on Friday afternoon, I went back to my classroom to collect my satchel. Bill Long was there, busy wiping off the blackboard with a duster, until interrupted by the Science Master, who came in to wish him a good weekend. Glancing up, I noticed the blackboard now read “B—–2 and underneath MU—–4.” Obsessed with thoughts of the Cup Final, I interpreted this as Blackpool 2 Manchester United 4 – an omen. When I drew Long’s attention to it, he laughed, saying, “No, no, no, that was Biology – period 2, Music – period 4,” adding, “Anyway Church, have a nice weekend and you can tell us about the game on Monday!”

Returning home, I sensed the excitement was building up. Mum had bought my first pair of long trousers, and Nan produced a new thermos flask – a tartan one from Woolworth’s – for the journey. After tea, Dad propped the two tickets up either side of the mantlepiece clock. We looked at them long and hard – the date read 24th April 1948.

In the morning, Dad went out and bought all the newspapers for my scrapbooks. I was at this time a follower of Blackpool and of their international stars, Stanley Matthews, Stan Mortensen and Harry Johnston. Naturally, Dad and I had a few bets on the correct score. I had two shillings on Blackpool to win 2-0 and 3-0, but after telling Dad about the blackboard omen, we felt it prudent to have two bob each on Man U. to win 4-2. The odds were 50-1.

The first half of our 40 minute train journey was taken up with Dad helpfully trying to pin an orange and white rosette securely onto my coat. Alighting at Waterloo, he was approached by a spiv ticket-tout, who offered him £5 each for our three-bob tickets – more than thirty times the price. This took Dad by surprise and for what seemed an age, he stood dithering in shock until, after looking across at me, he sent the tout packing. I later learned that Dad’s weekly wage was £9, so the tout’s offer was a massive temptation.

Inside Wembley stadium we located our position on the terraces – high up, overlooking one of the corner flags. The whole area was uncovered and the Tannoy system was difficult to hear, but I do remember the famous Arthur Caiger, in a white boiler suit, standing on a rostrum in the centre circle conducting Abide With Me, after both sets of supporters had given a full throttle rendition of Lassie from Lancashire. Finally, we were all asked to wave our song sheets for the cameras, a shot that the newsreels repeatedly used after a goal was scored.

Compared with Cup Finals today, it was a very strange experience; being so high in the crowd with only the sky above, it was comparatively quiet. There was no chanting and singing during the match as today, but the more dedicated fans would have wooden ‘air-raid’ rattles and some would have hand-knitted scarves with their players’ names stitched onto them. Most of the men, and they were more than 95% of the crowd, would shout out in desperation phrases like “Unload him Harry”, or “Fire it over”, “Let him have it”, or “Shoot” – all echoes of the recent war.

Up the other end, about a mile away, Blackpool scored from a penalty, but from where we stood, it seemed to happen in an eerie silence. I, of course, shouted “goal!” and jumped up and down, but there was little emotion around me and I remember how surreal the experience felt. In those days, almost two-thirds of the tickets went to clubs that had taken part in the earlier rounds, right down to the amateur clubs like Woking and Corinthian Casuals, so the strong partisan feelings of the teams supporters were confined to certain areas.

History has it that Jack Rowley of Man U. equalised after 27 minutes, before Mortensen, courtesy of a Matthews free-kick, put Blackpool 2-1 up at half-time.

It was difficult to sit down on the terraces, but we managed it, eating our sandwiches of corned beef and lettuce from the garden, washed down with tea from our new flask. Meanwhile, the breeze blew in an occasional piece of music from the brass bands playing below. Dad said he recognised his old favourite, “The Standard of St George”.

Blackpool’s lead evaporated in the second half, and I remember the men on a gantry, way up behind the goal, changing the enormous placards against the teams’ names to 2-2, then 2-3 and finally 2-4 for United. One lasting memory was of United’s Charlie Mitten, racing down the wing and repeatedly crossing the ball into the Blackpool goalmouth.

Eventually, we all drifted away. I felt very dejected, but Dad did his best to cheer me up. Then suddenly, I checked my betting slip and saw: Man U. 4-2 at 50-1. It seemed like a light in a dark tunnel – brilliant! Walking back down the Wembley Way, we checked our winnings – £5 each – the same amount the tout had offered us for our tickets.

Dad thought it was an amazing coincidence, and so did I.