The Origins and Foundation

of Racing at Epsom

Strangely, the events that led up to the foundation of the Derby started in the dry summer of 1618, when a humble herdsman, Henry Wicker, stumbled across a small hole full of water on the common, to the north-west of the turnpike road, between Epsom and Ashtead.

To Wicker’s amazement, after enlarging the hole in order to water his cattle, they refused to drink. And when he sampled it, neither would he. Some months later, samples of the water were examined by local physicians, who deemed it aluminous and recommended it for external use on cuts and sores. It was not until about 1830 that the highly purgative qualities of the water were discovered; this quite by chance, when a group of labourers drank deeply from the spring.

Epsom’s old wells

While at first knowledge of the waters remained local, word soon travelled to wealthy Londoners, whose appreciation of the remedy eventually brought patronage from the nobility of England, with Epsom then rivalling Tunbridge Wells for its famed cures.

John Toland, the famous religious writer noted, “Since it hath been inwardly taken, diseases have met with their cure, though they proceed from contrary causes.” He also observed that citizens of London arriving “from the worst of smokes to the best of airs”, quickly found themselves restored to perfect health. Very soon, the waters were amongst the most analysed substances in England (one gallon of water containing 480 grains of calcareous nitre), with entrepreneurs extracting and selling what became known as Epsom Salts at extravagant prices – five shillings an ounce being recorded in 1640.

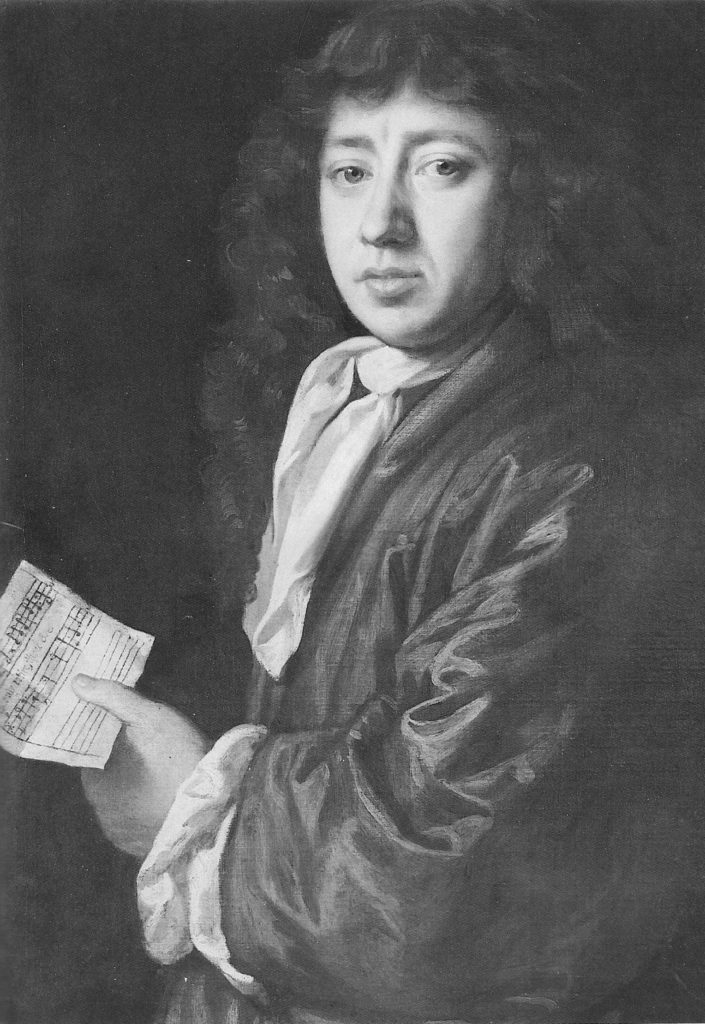

Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary of 1667, “We got to Epsom by 8 a-clock to the Well, where much company; and there we light and I drank the water; they did not, but do go about and walk a little among the women, but I did drink four pints and had some very good stools by it.” Later he visited the King’s Head, the nearest inn to the Downs, “where our coachman carried us; and there had an ill room for us to go into, but the best in the house that was not taken up; here we called for drink and a bespoke dinner. And hear that my Lord Buckhurst and Nelly (Nell Gwynne, the King’s mistress), is lodged at the next house, and keeps a merry house.”

Lord Buckhurst was described by Beauclerk as, “Cultured, witty, satirical, dissolute, and utterly charming”. Pepys reports the news on 13 July: “[Mr. Pierce tells us] Lord Buckhurst hath got Nell away from the King’s house, lies with her, and gives her £100 a year, so she hath sent her parts to the house, and will act no more.” However, Beauclerk later informs us “Nell Gwynne was acting once more in late August, and her brief affair with Buckhurst had ended.”

Pepys, himself was enamoured with Nell Gwynne and kept this Richard Thomson engraving of her as Cupid c.1672, above his desk at the Admiralty.

By the year 1690, after the many improvements made by Mr Parkhurst, Lord of the Manor, the village of Epsom had grown into a thriving town, and the humble shed originally erected for the convenience of invalids had now been replaced by a sumptuous ballroom.

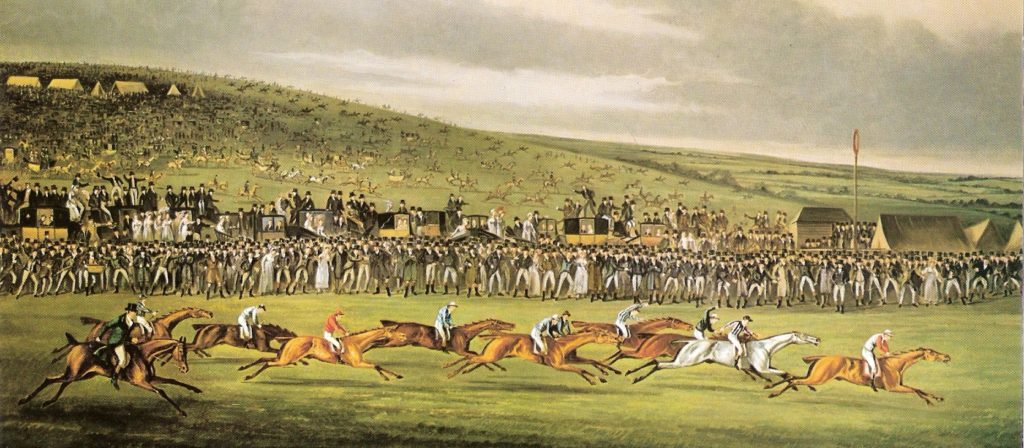

Henry Pownall, in his History of Epsom, published in 1825, said, “It became the centre of fashion; several houses were erected for lodgings, and yet the place would not contain all the visitors, many of whom were obliged to seek for accommodation in the neighbouring villages. Taverns, at that time reputed to be the largest in England, were opened; sedan chairs and numbered coaches attended. There was a public breakfast with dancing and music, every morning at the wells. There was also a (betting) ring as in Hyde Park; and on the downs, races were held daily at noon; with cudgelling and wrestling matches, foot races etc., in the afternoon. The evenings were usually spent in private parties, assemblies or cards; and may we add, that neither Bath nor Tunbridge ever boasted of more noble visitors than Epsom, or exceeded it in its splendour, at the time we are describing.”

The earliest indications of horseracing on Banstead (Epsom) Downs are in the 1640’s. In mid-May 1648, during the throes of the Civil War, the Earl of Clarendon in his History of the Rebellion relates, “a meeting of the royalists was held on Banstead Downs, under the pretence of a horse race, and six hundred horses were collected and marched to Reigate.”

This suggests that for such an undercover rendezvous to take place racing at Epsom must have been a regular and well-attended occasion. Under the Commonwealth (1649-60), horseracing was banned, but upon its demise, the first recorded race meeting in the country took place at Epsom on 7 March, 1661, in the presence of Charles II.

Two years later, on 27 May, Pepys wrote in his diary, “This day there was a great thronging to Banstead Downes, upon a great horse race and a foot race; I am sorry I could not go thither.”

To be continued later in Part Two