George Stubbs

1724 – 1806

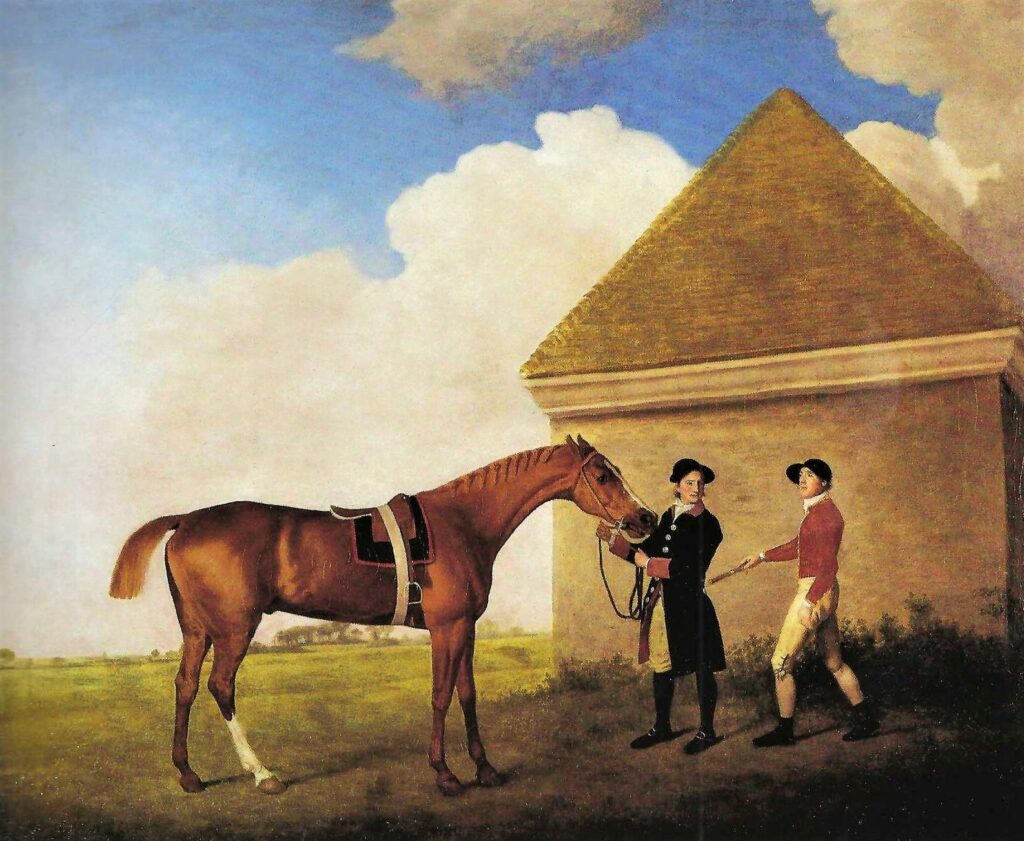

Eclipse by Stubbs, outside the Rubbing House on Newmarket Heath, c1770.

George Stubbs was born in Liverpool on the 25 August 1724, the son of John Stubbs, a leather currier and his wife Mary. After working for his father until 15 or 16, during which he developed a love of drawing, he expressed a wish to become a painter and with his father’s eventual consent he became a pupil of the Lancashire painter, Hamlet Winstanley. Soon after, having shown signs of ability, he was for a few weeks, allowed to study and copy Lord Derby’s Paintings at Knowsley Hall, near Liverpool. Thereafter, he taught himself at home, supported by his mother for four years.

From 1745 to 1753 he worked as a portrait painter and following his passion for anatomy, studied at the York County Hospital under Surgeon, Charles Atkinson. Within this period, he illustrated with 18 plates, John Burton’s Essay towards a Complete New System of Midwifery, published in 1751 and recognised as his earliest known work.

In 1754 he made the trip to Rome, contemplating and convincing himself that nature was superior to either Greek or Roman art. Then on returning to Liverpool he turned to portraiture of animals sometimes based on dissecting.

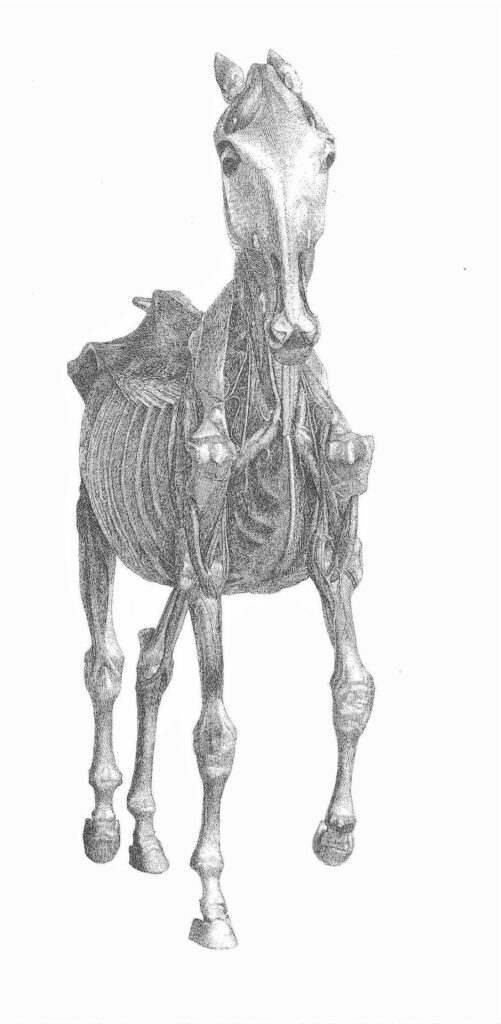

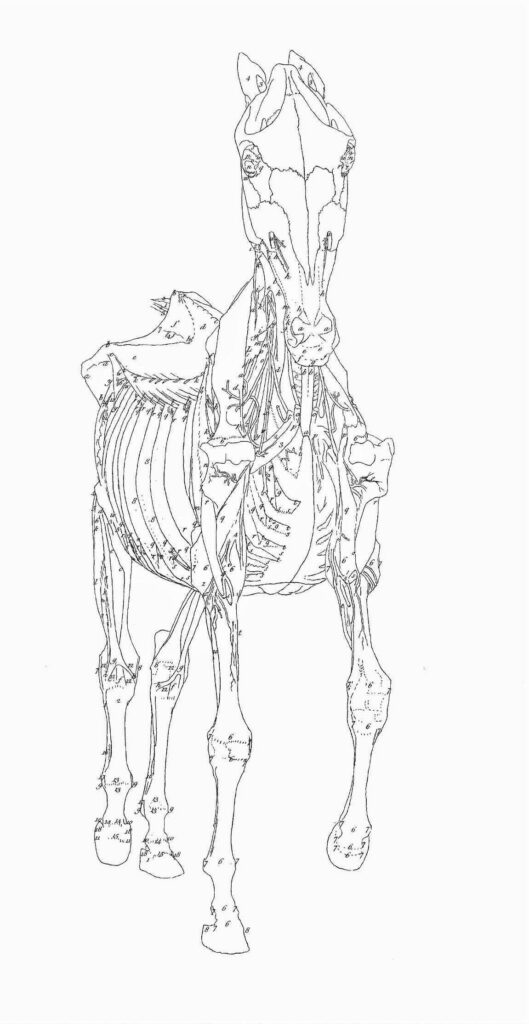

In 1756, convinced dissecting horses was the way to accurate portraiture, he rented a farmhouse in Hawkstow, Lincolnshire, where for 16 months, assisted by his common-law wife Mary Spencer, he set about dissecting horses; this a gruesome process which has to be described to appreciate the magnitude of the task. First he would sever the jugular vein, so quickly bleeding the horse to death, then to keep the shape of the veins and arteries he would inject them with a wax-like substance.

Stubbs then, fulfilling the plan of his drawings, fixed iron hooks into the farmhouse ceiling and assembled pulley’s that could draw and suspend a horse in a natural position, leaving its hooves resting upon a plank. He then proceeded to dissect the horse for about six weeks until the work was no longer useful.

Taking his drawings to London in 1758, he was unable to find a professional engraver willing to do the work. And it is probable that at this point he left Mary and their four children in Liverpool, while he established himself in London.

His paintings of horses and wild animals quickly enhanced his reputation with sales to the Dukes of Richmond and Grafton and the Earls Grosvenor and Spencer.

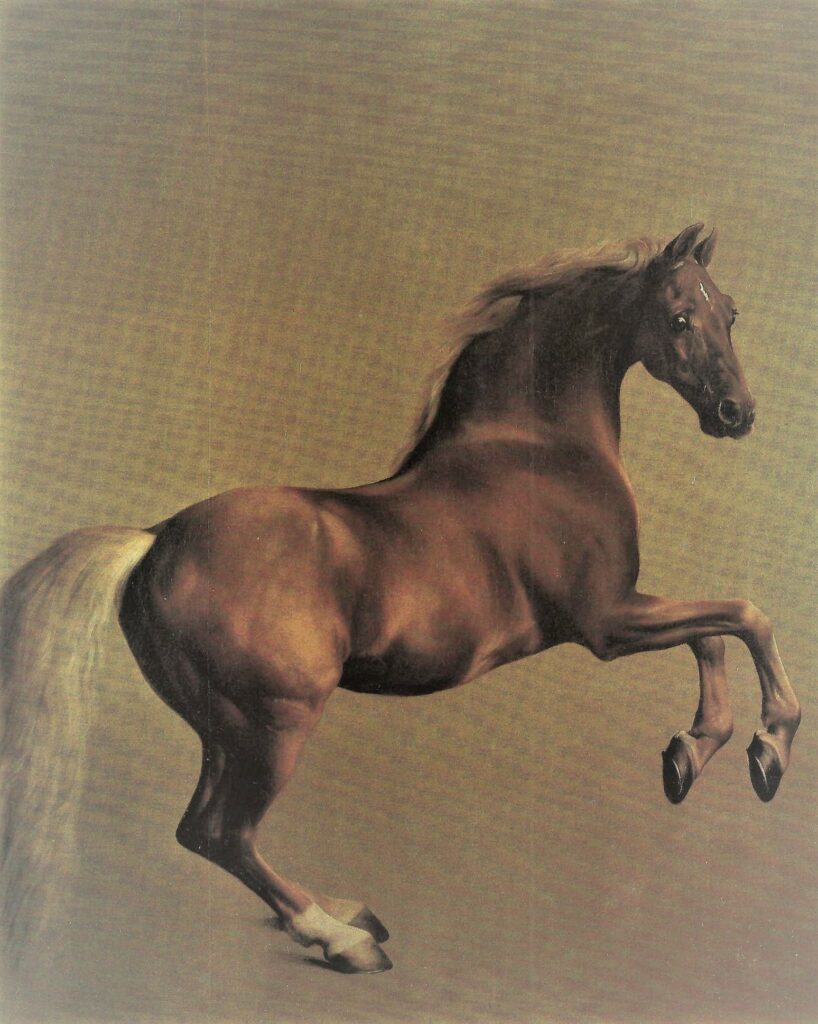

In 1762, Charles Watson-Wentworth, the 2nd Marquess of Rockingham (later Prime Minister in 1765 and 1782), commissioned the large painting of Whistlejacket, now in the National Gallery,

This I have complemented below with pedigree and racing record.

Whistlejacket ch.c. 1749 by Mogul (a son of the Godolphin Arabian), ex 1736 daughter of Bolton’s Sweepstakes.

Bred & owned by Sir William Middleton, later owned by the 2nd Marquess of Rockingham.

Won 13 races (from 17 starts) incl. a £2,000 Match over 4 miles at York, beating Mr Turner’s Brutus.

Soon after the acclaim of his Whistlejacket painting, Stubbs moved into 24 Somerset Street (later Selfridge’s), and began a series of ten variations of his Brood Mares and Foals, a subject popular with breeders of racehorses. His commissions now multiplying forced his work on the 18 Anatomy engravings back to either early morning or late at night. Nevertheless, he would develop a masterly talent as an engraver by the time The Anatomy of the Horse was published in 1766.

In 1770, Stubbs painted Captain O’Kelly’s famous horse Eclipse, who having recently retired to stud after an unbeaten career of 18 races he set with groom and jockey, before the Rubbing House on Newmarket Heath.

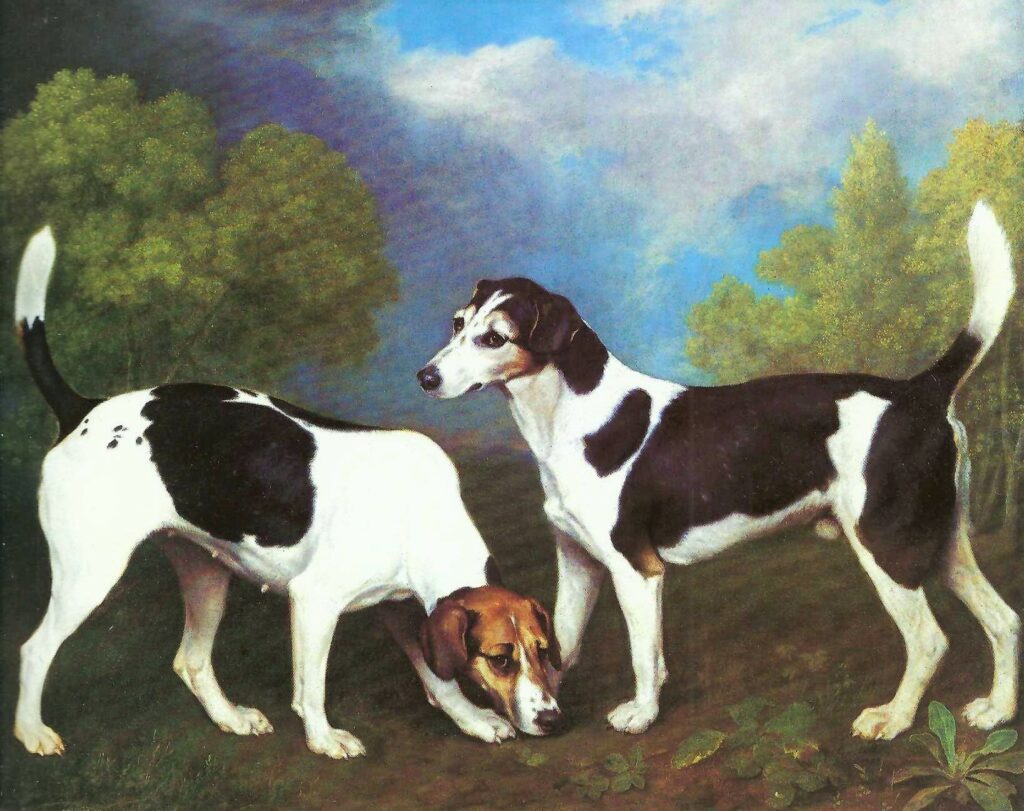

At this time Stubbs took up painting portraits of dogs, which led to many commissions. In fact, when making his début at the Royal Academy in 1775, two of his four exhibits were of dogs. Stubbs sense of design would maximise the build of the dog to occupy the major part of the painting. The finest examples of these being the two portraits of Foxhounds, painted in 1792: Ringwood, a Brocklesby Foxhound (Earl of Yarborough) and see below, A Couple of Foxhounds (Tate Gallery).

In 1795 Stubbs commenced his work, A comparative anatomical exposition of the structure of the human body with that of a tiger and a common fowl. The common fowl was easily bought and a nearby menagerie was able to supply the body of a tiger. Here one must credit Stubbs with the researching the problem of a dead body before he planned the work, which was likely made possible by a contact at St Thomas’s Hospital, where it was legal to receive the bodies of executed criminals for dissection.

Stubbs’ progress with drawings and engravings once again had to be fitted between his other commissions and sadly this time the work was not completed before his death.

What he did find time for in 1800 was his magnificent large painting of Hambletonian, but more of that when I will tell of the painting, the court case and, the match with Diamond in my next posting.

On the day of his death, 10 July 1806, at his home in Somerset Street, he made a new will, leaving everything to Mary Spencer (his common-law wife of more than 50 years), and appointed Mary Spencer and Isabella Saltonstall as joint executors. However, while suffering ‘violent spasms’, he was unable to sign it. Fortunately, after attestations by witnesses, it was accepted for probate.

To conclude, I would like to leave a final observation from Judy Egerton, the late Australian-born British art historian and curator.

Stubbs is perhaps a deceptive artist: some of his subjects seem so ‘ordinary’ that their extraordinary ability to move the spectator takes a second glance to manifest itself. In this his reticence is characteristically English, akin to that style which Jane Austen describes as ‘burying under a calmness that seems all but indifference, the real attachment’.

*******************************************************************************************************************************************************************************************

On a personal level, I first discovered The Anatomy of the Horse just after the war, when aged nine. Family reunions at Auntie Mary’s in Church Street, Woking, were a frequent occurrence and while the adults discussed food rationing, politics and horseracing, I was kept quiet with this lovely large book with pictures of horse anatomy. Recently, I found the same 1938 edition for sale at a good price and so after reliving my childhood memories I set about writing this essay.