Michael Church Racing Books

Archive for 2018

Tragedy and Scandal – The Suffragette Derby

Tragedy and Scandal

The Suffragette Derby of 1913

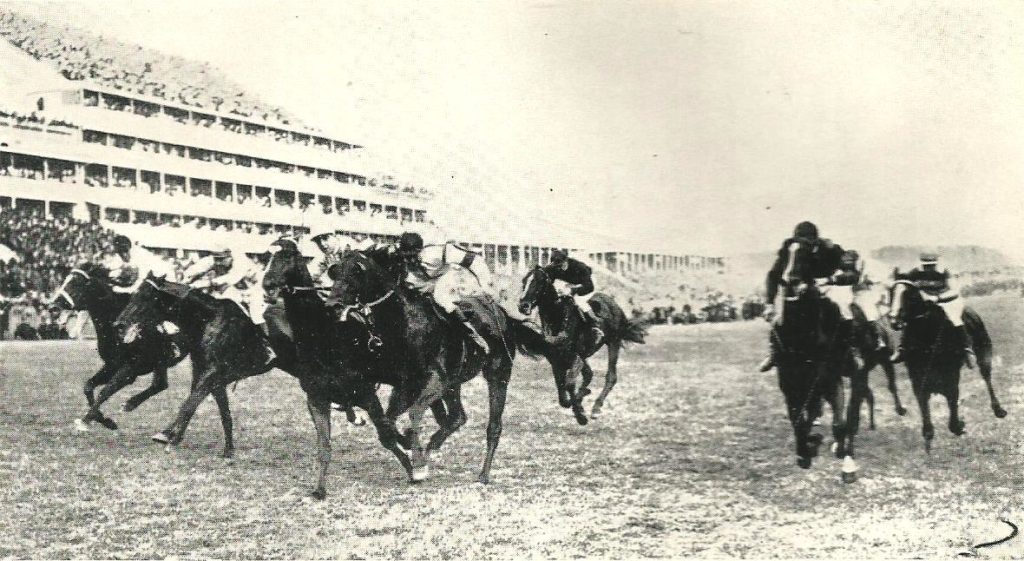

On Derby Day, 1913, two dramas were played out on Epsom Downs before a crowd of half a million people – one a tragedy, the other a scandal.

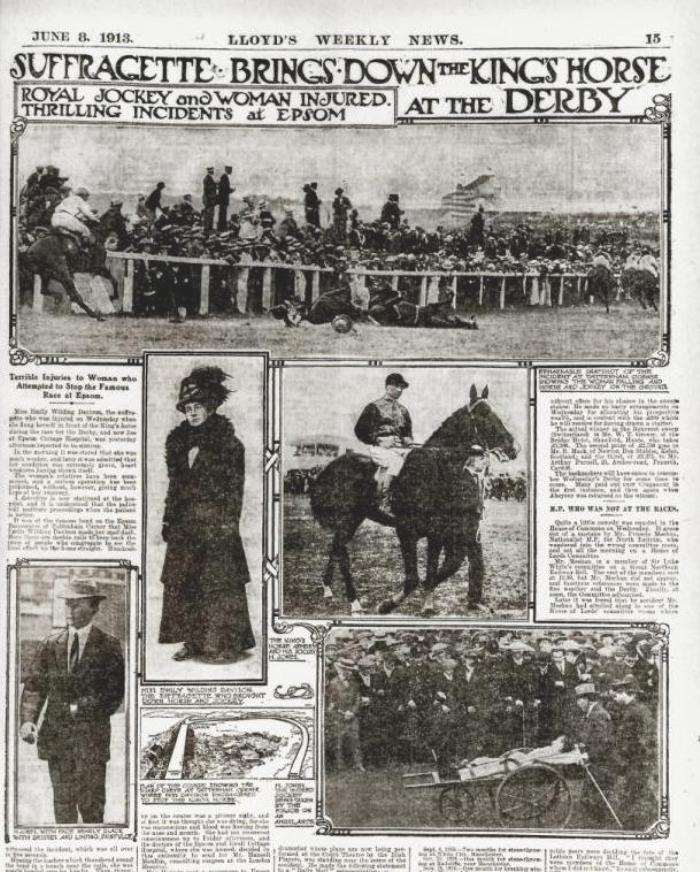

As the field swept round Tattenham Corner, a protesting suffragette, came from under the rails into the middle of the race, fatefully, bringing down the King’s horse and jockey and so creating the iconic moment for the Suffragist movement.

Minutes later, the stewards brushing aside the incident, formed an incomplete quorum, to disqualify the winning favourite amid claims of prejudice and personal vendetta. The promoted winner started at 100-1, and the horse that finished third was not placed by the judge. These events and the motives behind them headlined the news for many days.

The Suffragette, Emily Wilding Davison was born on 11 October 1872, in Blackheath, London, but lived in Longhorsley, Northumberland. After attaining B.A. Honours at the Royal Holloway College, she went on to study English Language and Literature at St Hugh’s College, Oxford, where she won first class honours.

However, and this may have proved significant, women, at that time, were not admitted to obtain degrees at Oxford. In 1906, Emily joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, known as the WSPU, a movement led by Emmeline Pankhurst, who defiantly believed that ‘direct action’ would lead to women gaining the vote.

Three years later, Emily gave up her position as teacher to a family in Berkshire, in order to promote the cause of women’s suffrage and very quickly came to the forefront of the ‘direct action’ groups. Although her police record has little to do with the Derby, it is only with the knowledge of her dedication and fervency that her action at Tattenham Corner can be understood.

Never one for compromise, Emily once barricaded herself in her cell to avoid being force-fed, only for a prison officer to force a nozzle of a hosepipe through the window, to drench her and flood her cell. On another occasion, in protest to her fellow suffragist’s being force-fed, when not on hunger strike, she jumped down an iron staircase and received severe spinal injuries.

Her seven prison sentences included six months for setting fire to post boxes in Holloway. There she soaked rags in paraffin, set them alight and then pushed them into the boxes – a crime that started a wave of similar incidents. Sentenced at the Old Bailey and force-fed, she was released only 10 days before the end of her sentence due to injuries incurred. Emily was also imprisoned for 10 days for assaulting a Baptist Minister with a dog whip in Aberdeen, mistakenly identifying him as David Lloyd George. Mercifully, she was released after four days’ hunger strike. Although completely dedicated to the cause, Emily Davison was regarded by many in the movement as a maverick and few if any, knew what disruption she had planned for Derby Day.

On the morning of Wednesday, 4 June, 1913, Emily took two large flags of the suffragist colours – green, white and purple stripes – folded them into a large pad and pinned them inside the back of her jacket, possibly for a demonstration. She then travelled to Victoria Station where she notably bought a return ticket to the Tattenham Corner Station at Epsom.

The Derby was the third race of the afternoon. Emily stood towards the end of Tattenham Corner, about ten rows back from the rails and, directly opposite the Movie cameras. Significantly, this was the first race where the horses were to come around Tattenham Corner; the two previous races over five furlongs having started opposite her, from a shoot to the straight.

Fifteen runners went to post on a bright but cloudy day. Mary Richardson, who stood with Emily at Tattenham Corner, wrote of the incident in her book Laugh a Defiance:

“A minute before the race started she raised a paper on her own or some kind of card before her eyes. I was watching her hand. It did not shake. Even when I heard the pounding of horses’ hoofs moving closer I saw she was still smiling. And suddenly she slipped under the rail and ran out into the middle of the racecourse. It was all over so quickly.”

The author, having watched the flickering film, frame-by-frame many times, can confirm that after nine of the 15 runners had past there was a gap of a few yards, into which Davison, dressed in a large black coat and hat, slipped under the running rail holding what looked like a sheet of paper, perhaps a petition. Moving towards the next on-coming horse – Agadir – she stepped aside. Two more horses passed close by and in each case her attempt to grab their bridle was unsuccessful. Then, after a space of about four lengths, Emily stood purposely in front of the next horse, Anmer, owned by King George V and putting her hands up, apparently to grab the bridle, she was forcibly bowled over by the horse, who, a split-second later crashed to the ground, taking Herbert Jones, trapped in a stirrup, down with him.

Photographs show that apart from those spectators on the rail in front of the incident, most of the crowd were intent on following the race around the bend. However, seconds later, people rushed towards the stricken parties from the other side of the course.

In retrospect, it seems highly unlikely that Emily, without hearing any form of race commentary, would have known where in the running order the King’s horse would have been. Also, from her position, surrounded by spectators, some standing on top of carriages, she was unlikely to have seen the first batch of runners coming until they were upon her. Ironically, the first horse she made contact with, was the King’s horse and so doing brought her martyrdom the maximum publicity.

Fortunately, the cinematograph operators of the Gaumont Company were situated on the other side of the course, opposite the incident. With great initiative the film was shown that evening at the Hippodrome and Coliseum Theatres and later, at many other London and provincial cinemas.

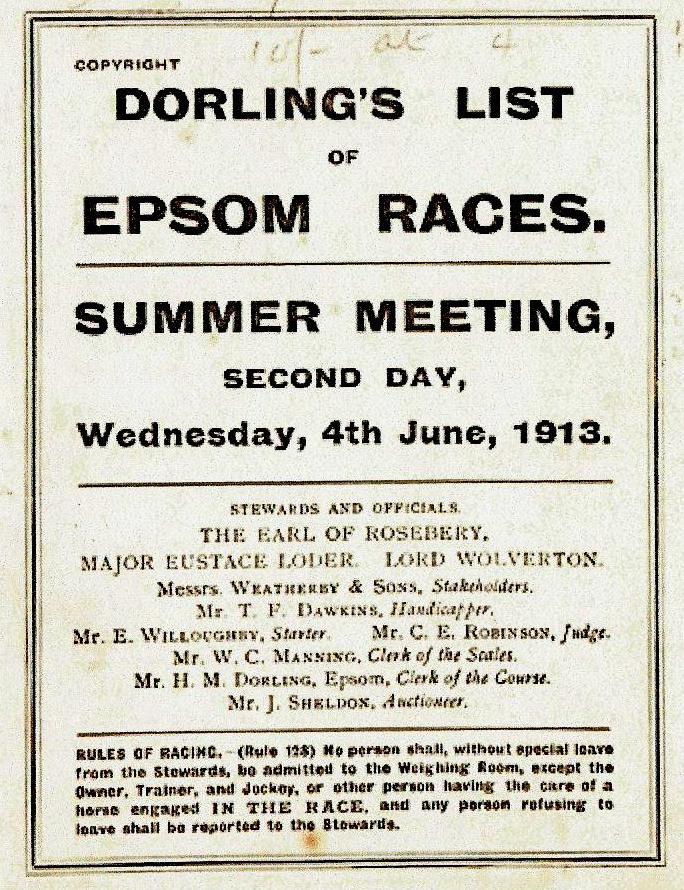

An examination of Emily’s pockets after the race included the racecard, known as Dorling’s List, a helpers pass for the WSPU Kensington festival and a handkerchief bearing her name, which quickly proved her identity.

In the aftermath, Miss Davison was taken to Epsom Cottage Hospital, where she never regained consciousness and died on 8 June, 1913. Her death certificate confirmed a “fracture of the base of the skull caused by being accidentally knocked down by a horse through wilfully rushing onto the racecourse at Epsom Downs”.

Herbert Jones, also found unconscious, was first taken up the course on a wheeled stretcher to the weighing in room. When unable to get through the door, he was taken to a room at the back of the stands. His examination revealed a fractured rib, cuts and bruises on the body and a black eye. On regaining consciousness, he was taken to the Great Eastern Hotel, Liverpool Street, where he stayed the following day, returning to Newmarket on the Friday.

Lloyds Weekly News reported:

“Asked if he remembered anything about the incident, Jones said the woman seemed to clutch at his horse, and he felt it strike her…. He asked after the suffragette who had brought him down, and there was only kindness in his voice.”

The King’s horse Anmer, although suffering bruises recovered amazingly well, reappearing in the Ascot Derby two weeks later. However, he failed to win another race, either that year or the next.

Whilst the popular press showed great sympathy in covering Miss Davison’s death, in contrast, almost all the racing fraternity were angered by her intrusion. The Racing Calendar’s minimal report stated: “Anmer was interfered with by a spectator and fell.”

The funeral of Emily Davison was not only noble and impressive, but it became the iconic event in women’s suffrage. Starting from Victoria Station 6,000 suffragists, many dressed in white and carrying white lilies, marched through streets to St George’s Church in Bloomsbury, where the funeral took place. The coffin and attendants, then travelled by train from King’s Cross Station to Newcastle and finally, to the churchyard of St Mary the Virgin, Morpeth in Northumberland, where 30,000 people attended. Her gravestone bore the WSPU slogan “Deeds not words”.

Fatefully, it is worth considering, had Emily stepped on to the racecourse a few seconds earlier, she would have brought down half the field and their jockeys, perhaps causing deaths other than her own. A few seconds later, the horses would all have passed and the incident would have been reduced to a footnote.

To move from the tragedy to the scandal – the prejudice that caused Craganour to be disqualified had its origin in the sinking of the Titanic the year before.

Charles Bower Ismay, owner of Craganour, was the younger brother Bruce Ismay, the Managing Director of the White Star Line, who was rescued from the Titanic, when 1,517 others lost their lives. In the following enquiry set up by the United States Senate, Bruce was strongly criticised by the Hearst Press, who roundly accused him of cowardice. Later, although a British inquiry exonerated him, the stain on the family’s reputation remained. The two brothers were close, Bower Ismay having married the sister of Bruce Ismay’s wife.

In consequence, the prejudice against the Ismay’s was widespread and brought to bear when Craganour, appearing to win the Two Thousand Guineas, was overlooked by the judge in favour of Louviers, despite press photographs clearly showing the opposite.

Major Eustace Loder’s involvement came originally as the breeder of Craganour, the colt fetching 3,200 guineas – the top price at the 1911 September Doncaster Sales – knocked down to Charles Bower Ismay. Later, to compound matters, he believed Ismay to have had affair with his sister-in-law.

The eventual winner of the 1913 Derby, Aboyeur, had shown promise when winning the Champagne Stakes at Salisbury. However, after running poorly in the Easter Stakes at Kempton on his three-year-old debut, his Derby odds drifted to 100-1.

In the Race, rounding Tattenham Corner, Aboyeur led the field from Craganour, until turning into the straight, where Craganour, ridden by Johnny Reiff (a fearless American Jockey) bumped Aboyeur, sending him to the rails, so cutting off Shogun. In the final furlong, Aboyeur, under pressure from Edwin Piper’s whip, continually leant into Craganour as the pair moved off the rails. They passed the post together, but Craganour’s number was hoisted as the winner.

Charles Bower Ismay led in his colt and the ‘all right’ was given. But as Craganour was led away, Lord Durham rushed out to announce a stewards’ inquiry and an objection to the winner. Strangely, Aboyeur’s owner Alan Cunliffe, a shrewd gambler who stood to win nearly £40,000, had seen no reason to object – the objection came from the stewards.

Initiated solely by Major Eustace Loder, but with the support of Lord Wolverton, they formed an unchallenged quorum of two, after the remaining stewards had declared a personal interest. After a lengthy period during which another race was run, the verdict came: Craganour was disqualified and placed last on the grounds that he had jostled Aboyeur, caused serious interference to three other runners, and had ‘bumped and bored Aboyeur so as to prevent his winning’. Incredibly, Ismay’s notice of appeal to the clerk of the course was received a day outside the appeal deadline. Adding to the confusion, Day Comet, who had finished third but was obscured from the judge’s view, was assigned no official place and the error was never corrected.

In the days that followed, there was some strong criticism of what was considered a harsh decision. Mayrick Good of The Sporting Life wrote:

“I have no hesitation in stating that in my opinion Aboyeur was the real transgressor. No one had a better view of the race than I, and that was my conclusion. Nothing I have heard since has ever induced me to change that view.”

A week after the Derby, Ismay, now realising Craganour had no future in Britain, either on the racecourse or at stud, sold the colt to Senor Martinez de Hoz, owner of the famous Chapadmalal Stud in Argentina, for £30,000 (over £2 million today).

Aboyeur ran twice more, finishing third in the St George Stakes at Liverpool and second in the Gordon Stakes at Goodwood. He was then sold for 13,000 guineas to the Imperial Racing Club at St Petersburg in Russia before disappearing in the Russian Revolution.

Major Eustace Loder (1867-1914), was a successful breeder and owner. In 1906, he won the Derby with Spearmint, although his best horse by far, was Pretty Polly, adored by the public she won of 22 of her 24 races, including the Fillies’ Triple Crown in 1904. Controversially, Loder is remembered for his part in the disqualification of Craganour, the publicity and consequences of which left its mark and he died a year later aged 47.

Returning to the Suffragette cause, a daggers drawn altercation had developed between Emmeline Pankhurst and David Lloyd George.

On 20 February 1913, after The Times reported: ‘An attempt was made yesterday morning to blow up a house which is being built for Mr Lloyd George, near Walton Heath Golf Links’. That evening, at a meeting in Cory Hall Cardiff, Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the militant suffragette society, the Women’s Social and Political Union, proclaimed ‘we have blown up the Chancellor of Exchequer’s house’ and, ‘for all that has been done in the past I accept responsibility.

However, all was to change with the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. Firstly, all the imprisoned suffragettes were released unconditionally. After which, Mrs Pankhurst recommended a temporary suspension of militant activities, calling for her followers to actively campaign for women’s war work.

In 1915, after a crucial need for a million more shells, Lloyd George, now Minister of Munitions, met with Mrs Pankhurst, suggesting she led a Women’s Right to Serve demonstration to overcome trade union opposition to female labour. She did, and within months 80% of the munitions’ workforces were women. Known as ‘Munitionettes’ they produced a continual flow of 18lb shells to win the war.

In 1918, citing the work carried out by women during the First World War, the Government gave women the vote if over 30 years of age and a property owner, or married to a property owner. Ten years later, the age limit for women was reduced to 21, the same as for men.

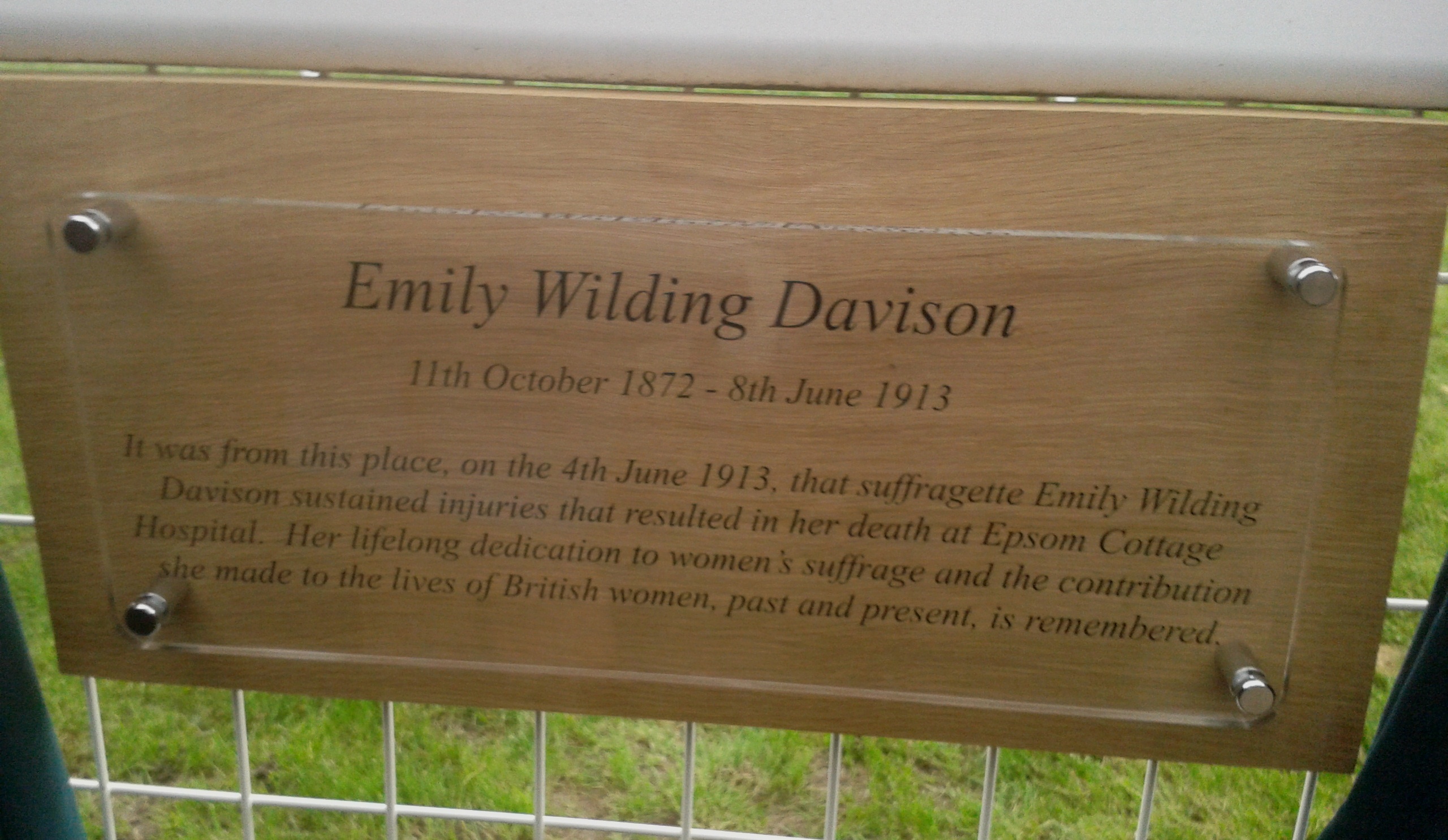

A centenary after the tragedy on Epsom racecourse, the Jockey Club unveiled a commemorative plaque to Emily Wilding Davison on the rails at Tattenham Corner.

The unveiling ceremony on Thursday, 18 April 2013, was attended by, “the largest gathering of Emily’s descendants and relatives to date”.