Mary’s Boxing Day Bet

Christmas Day was always kept at home with the family; Mum, Dad, Nan, Judy the dog and me. With similar regularity, on Boxing Day, we walked from our little bungalow in Clarence Avenue, Woking, to Auntie Mary’s terraced house in Church Street, a distance of 500 yards exactly.

I was quite sure of that, having regularly paced the journey to visit my cousin Peter on Sunday mornings. And, significant to me, a 14-year-old boy on the slippery slope (see below), as the standard distance at Wimbledon dog track.

Greeted at the door of 199 by Mary, Henry and Peter, we were shown to their front room. A welcoming sight, with its colourful paper chains, large paper bells, sprigs of holly and a small artificial tree covered in lights.

“Henry fixed the lights just an hour ago,” Mary said joyfully.

“One of the bulbs had worked loose, but we didn’t know which one!” her voice booming with the sense of occasion.

To cross the room, however, was in truth, akin to crossing a minefield, for another of Dad’s brothers, Albert, owning the property and renting it to Henry, had done nothing to repair the dry rot that lurked perilously beneath the freshly hoovered carpet.

“Mind how you go Stan,” Mary cautioned, shepherding in Dad like the usherette she once was.

“The seat over by the fireplace is quite safe, and Dorothy, if you sit on the settee with me.” Then in a hushed and dignified tone, added, “We put two large metal trays under the casters to save us falling through.”

Warming to her roll as hostess, Mary directed, “Oh Henry, go into the kitchen and get us all a cup of tea and a mince pie, and Nan, there’s a wicker chair for you under the radio.”

Peter and I, a little squeezed for room, were told to play in the kitchen, “You know, the game you like to play on Sunday mornings,” Mary continued, tirelessly, “Guessing the football crowds in the paper, I’ve saved last Sunday’s News of the World ‘specially for you.”

Hardly a school certificate subject, but perhaps it should have been, since we both excelled at it. Anyway, true to form, Mary had put up a children’s see-through Christmas stocking as a prize for the winner – the ones with chocolate money, sugar mice and those tiny packs of playing cards with Scotty dogs on the back. Oh, and those small tin scales to weigh sweets on. Not much for a 14-year-old boy you might say, but then, Mary called out from the front room that she had included Old Moore’s Almanack.

“It usually gives some veiled hints for next years Derby and Grand National. And somewhere in there,” she enthused, “there’s trap numbers to back in reversed forecasts for all the London dog tracks!”

An hour later, I was enjoying a thumb through Old Moore’s, a little guiltily I must confess, since it had fallen to me to guess the Blackpool home crowd, which as every schoolboy knew, was invariably a capacity 30,000 – like taking a penalty kick really.

Anyway, Henry topped us up with more tea and mince pies on yet another tin tray – The Laughing Cavalier this time. If there was one thing Auntie Mary had in spades it was tin trays – multi-purposed in her house!

Meanwhile, spirits were high in the front room, with Mary telling Mum how her friend Phyllis, had, during the war, seen the King and Queen inspecting the bomb damage in the East End of London.

“They were very friendly, Phyllis told me, and she gave me the cuttings out of her News Chronicle – for my Royal scrapbooks you know.”

Auntie Mary was a devout Royalist; she had dozens of these scrapbooks, allegedly, full of Royal births, deaths and marriages, even pictures of past Royal Ascots – so she said.

However, mysteriously, as yet, we had never seen any of them, and, despite our enthusiasm, we didn’t see them today either.

Suddenly, there was a knock at the door. Mary, peering round the aspidistra and, slightly twitching the net curtain, “Bloody hell it’s Albert, surely he hasn’t come for the rent on Boxing day?”

Albert entered with his usual cocky smile, to produce from behind his back with a flourish, a bag containing a bottle of Sandiman’s port, a Christmas pudding, laced with brandy and a wrapper containing 200 Craven A ciggies, the ones with the black cat on the box – the latter a life or death line for Mary and Henry. Then, going back to his Fish van, parked across the road, he returned with an oblong wooden box – a top grade Scottish salmon – “A rarity, even among the gentry,” said Albert with another broad grin. And, no, he hadn’t forgotten Peter either, who disappearing into the scullery with a brown paper parcel joyfully unwrapped a bright new red and white Woking football scarf.

Albert entered with his usual cocky smile, to produce from behind his back with a flourish, a bag containing a bottle of Sandiman’s port, a Christmas pudding, laced with brandy and a wrapper containing 200 Craven A ciggies, the ones with the black cat on the box – the latter a life or death line for Mary and Henry. Then, going back to his Fish van, parked across the road, he returned with an oblong wooden box – a top grade Scottish salmon – “A rarity, even among the gentry,” said Albert with another broad grin. And, no, he hadn’t forgotten Peter either, who disappearing into the scullery with a brown paper parcel joyfully unwrapped a bright new red and white Woking football scarf.

Mary seemed a little flummoxed at Albert’s sudden generosity and for once, untypically, steered him clear of the dangerous carpet zones.

In the meantime, my dad, oblivious to the latest turn of events, inevitably redirected the conversation to Woking’s recent 3-0 victory over Wimbledon, “Alfie Welland scored two and …” his account was suddenly interrupted by cheers of relief at Peter’s perfectly timed entrance in his pristine scarf.

Mary, meanwhile, was disappearing upstairs, when Albert, anxiously fearing that the weight of the gathering might prove costly, nervously called after her, “I can’t stay Mary, I’m just going to pick up Charlie; we’re going to Kempton.”

Mary returned, slightly out of breath, to ask in a confidential whisper,

“Do you know anything good?”

“Well, Charlie says the Queen’s got Manicou in the ‘King George’ and, it’s a live’un!”

Mary thrust a small white envelope into Albert’s hand, “Two weeks rent, Albert. Sorry for the delay, but it’s Christmas yer know.” She followed him out to the van.

“You’re a real brick Mary,” Albert said earnestly, turning to meet her face on, “That’s very much appreciated,” he said with a wink, “It’ll make my day!”

Mary started to hover from one foot to the other, like a little girl.

“Albert, that Queen’s horse Manna-something or other, would you put a bit on for me?” Albert nodded and with that, she slipped something into his overcoat pocket.

“Must fly now Mary”, said Albert, “Enjoy the salmon,” and with that, his fish van disappeared round the corner and out of sight.

Kempton was cold, bright and sunny and, there was a feeling of optimism amongst the packed crowd. The first three favourites had all gone in and now, the seven runners for the King George were making their way to post.

Albert, who had the questionable system of backing horses with the initial letters of A, C, and E in a treble, had already landed the first two legs with Easy Winner and Attentif, and was now sweating on Coloured School Boy in the big’un.

Just as the field came into line Albert remembered Mary’s bet and, thrusting his hand into his overcoat pocket, rushed up to Stringer’s joint in the front row and pushed the bet into his hand, shouting out, “Manicou, on the nose.”

There were no ‘big screens’, or even commentaries on racecourses in 1950, so binoculars of all shapes and sizes were trained up the home straight. First round the final bend was the ‘Blue; buff stripes, blue sleeves and black cap’ of Queen Elizabeth’s Manicou, who, although joined two out by Silver Fame (ridden by the future crime writer, Dick Francis), drew away to win by three lengths.

After the race, Uncles Charlie and Albert met up in front of the bookies. Charlie had collected a nice touch, while typically, Albert, having stayed faithful to his ACE system, had nothing to collect from third placed Coloured School Boy. Then, almost as an afterthought, he remembered Mary’s bet on Manicou, and rummaging in his pocket for the ticket, gave it to Charlie to collect.

Returning a few minutes later, with an expression of veiled incredulity, Charlie enquired cautiously, “How much did Mary have on that Queen’s horse?”

“Don’t know, exactly,” Albert said, “Stringer did say, but we were both in such a hurry I didn’t catch it,” continuing, “She had it wrapped up in an envelope.”

His hand slid back into his pocket and as it did, so Albert’s expression changed. Pulling out another envelope, he opened it – a ten bob note!

Mary’s two weeks rent had amounted to £6 and now, at 5-1 …“Blimey, I’ve put the rent money on,” Albert exclaimed, his conscience suddenly working overtime with the thoughts of, “If only I had collected the bet myself.”

Albert thrust out his hand to Charlie, “Give me the money, I’ll deduct the rent and pay Mary her winnings.”

“OK,” said Charlie, but knowing Albert of old, added, “But won’t Mary be delighted when I tell her she’s won £30. I’m sure she’ll forgive you the cock-up.”

Albert’s face was a study; for once, he had been completely thwarted,

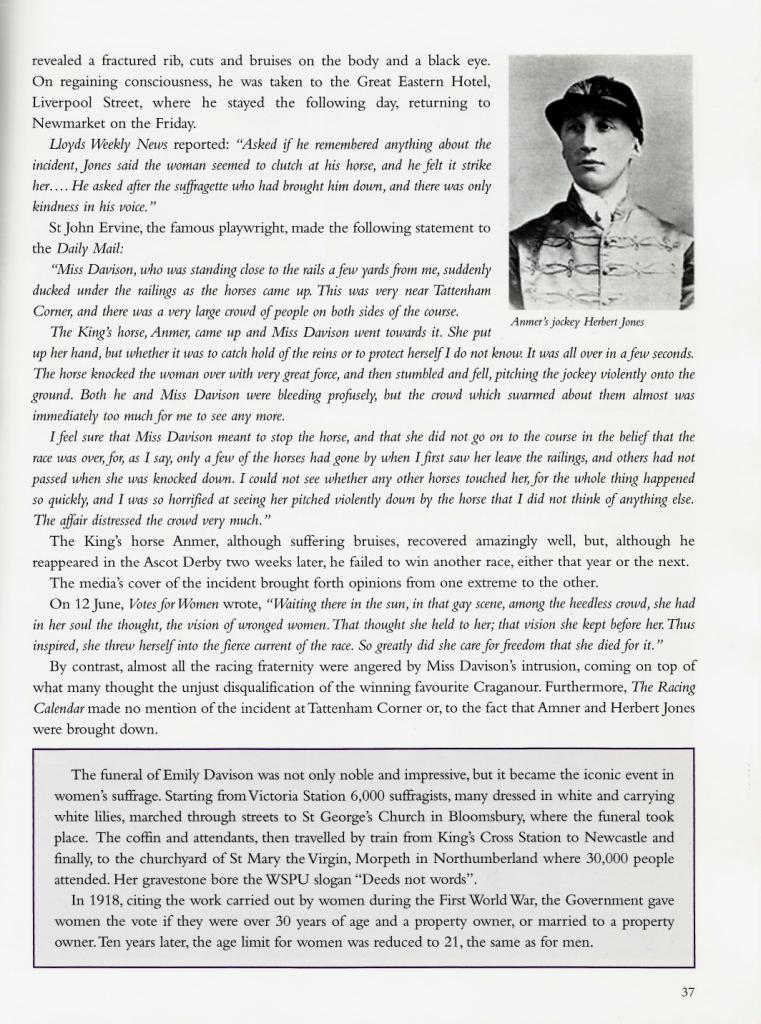

The story of Mary’s Boxing Day bet was often recalled at Christmas and on family holidays – see below, Mary, Henry & Peter, a few years later, on Brighton Pier.

This story comes from Michael’s Black Horse – Red Dog,

of which he has a few signed copies for sale.

See also his list of books for sale by clicking on Books for Sale

at the top of the page.

Next day, hoping to add to my run of luck, I watched the windows of the 8.27 as it arrived at Woking and, catching a glimpse of Monty, hurried along the platform to join him.

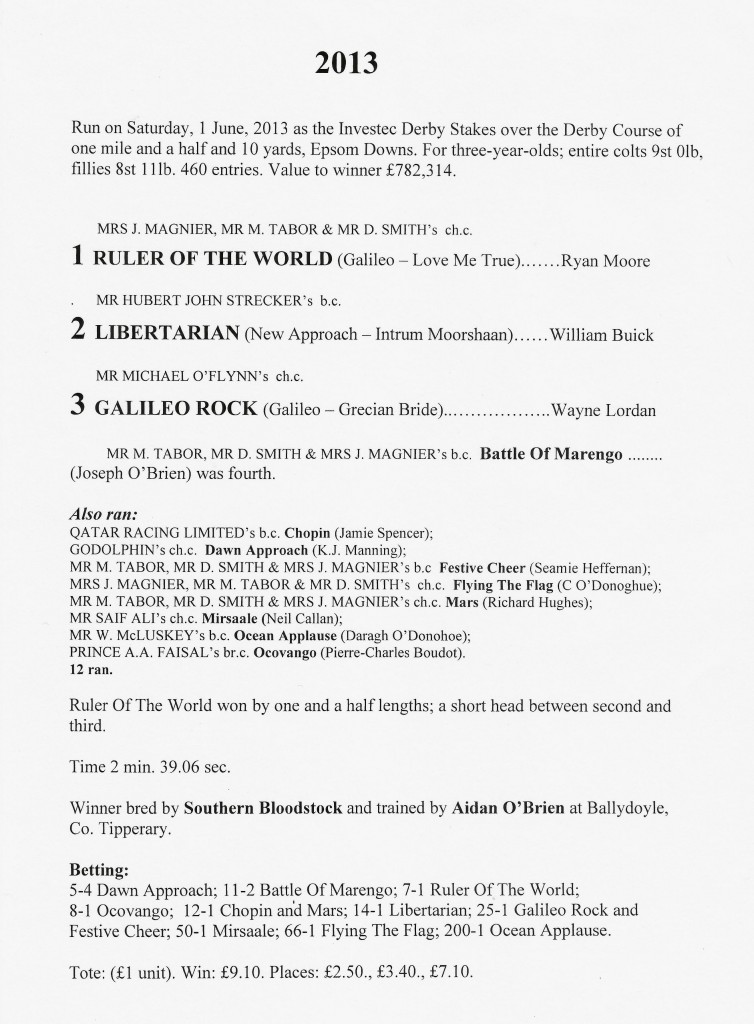

Next day, hoping to add to my run of luck, I watched the windows of the 8.27 as it arrived at Woking and, catching a glimpse of Monty, hurried along the platform to join him. Aidan O’Brien, saddled four for Ireland; three by the Champion Sire and 2001 Derby winner, Galileo, of which Battle Of Marengo (Joseph O’Brien), having won the Derrinstown Stud Derby Trial Stakes and Ruler Of The World (Ryan Moore), the Chester Vase, were the pick and, second and third favourites for the race.

Aidan O’Brien, saddled four for Ireland; three by the Champion Sire and 2001 Derby winner, Galileo, of which Battle Of Marengo (Joseph O’Brien), having won the Derrinstown Stud Derby Trial Stakes and Ruler Of The World (Ryan Moore), the Chester Vase, were the pick and, second and third favourites for the race.

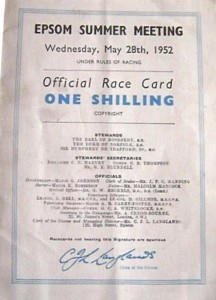

Early Wednesday morning, having got special permission from Headmaster, Bonk Peel, to have Derby Day off, I dropped into the hairdressers to hand in my family’s bets. Charlie and Alice, looking the worst for wear, were already occupied with a steady stream of shilling each-way’s and any-to-come’s. Alice confided, “Charlie’s furious with Solly – it isn’t the first time you know. If he doesn’t show and Tulyar loses, we’re buggered – it’s like doing a thousand hair cuts for nothing.”

Early Wednesday morning, having got special permission from Headmaster, Bonk Peel, to have Derby Day off, I dropped into the hairdressers to hand in my family’s bets. Charlie and Alice, looking the worst for wear, were already occupied with a steady stream of shilling each-way’s and any-to-come’s. Alice confided, “Charlie’s furious with Solly – it isn’t the first time you know. If he doesn’t show and Tulyar loses, we’re buggered – it’s like doing a thousand hair cuts for nothing.” Apparently, at the finish, my unrestrained celebrations had convinced a nearby policemen that I had made a full recovery and I was promptly escorted back into the enclosure.

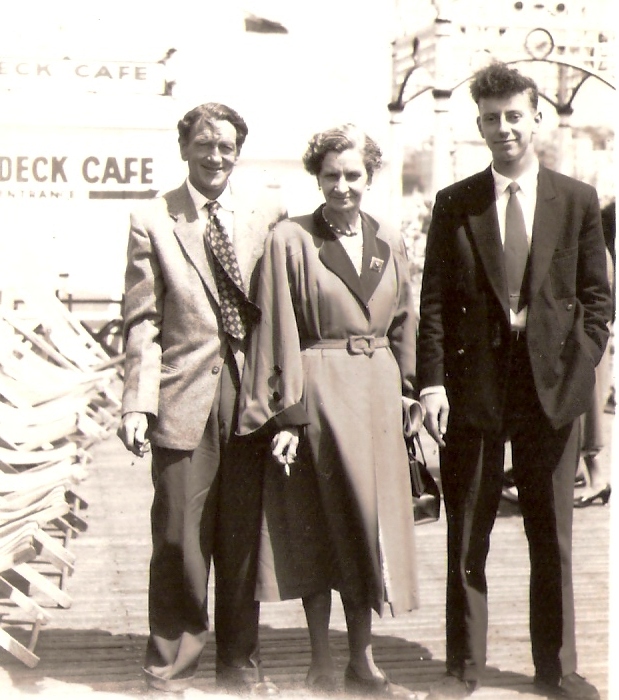

Apparently, at the finish, my unrestrained celebrations had convinced a nearby policemen that I had made a full recovery and I was promptly escorted back into the enclosure.