Harry Wragg and the Brylcreem Boy

I knocked twice on the dark stained door at the end of the passage.

A small hatch slid open.

“Oxo,” I said boldly, standing on tiptoe.

Alice let me in.

“Is the 1.15 off,” I enquired.

“You’ve got a few minutes yet,” she said, dragging on her Woodbine.

I entered the smoke-filled room where the usual crowd huddled around the ticker-tape machine, its stuttering chatter competing with the ringing telephones.

This is the back room of Charlie Young’s Hairdressing Salon and, as a chirpy, skinny ten-year-old, my excessive enthusiasm for racing and betting has led me to be accepted by all the regulars. Today is both the last day of the 1946 Flat Season and the last day in the riding career of Harry Wragg, so consequently, my last chance to back him.

Harry was the thinking man’s jockey, known nationally as ‘The Head Waiter’ because of his effective waiting tactics. He had been champion jockey in 1941, and ridden the winners of 13 Classic races, including three Derby winners – Felstead (in 1928), Blenheim (1930) and Watling Street (1942). He also had two younger brothers, Sam and Arthur who were both successful jockeys in their own right.

Time running out, I quickly scribbled my first bet, 2/- win Tiffin Bell, (Harry’s first mount), and slid it across to Charlie’s lanky blonde wife Alice, who promptly secured it among 50 or so others in a giant bulldog clip.

“Two lumps today, Alice,” I piped, reaching for the obligatory cup of tea. But before I had put the cup to my lips, Uncle Albert shouted across “Result Manchester – 1.15 – first Tiffin Bell – 5-2.”

“Blimey, I’m off to a good start,” I squeaked.

During the next 30 minutes, a pipe and two Capstan full strength passed through the security system and quickly contributed to the diminishing visibility.

Continuing my loyalty to H. Wragg, I invested 2/- to win on Aprolon in the next, and made myself useful by taking a tray of tea and biscuits out to Charlie in the shop.

Charlie, a dead ringer for Alfred Hitchcock, often used his ventriloquist talents whilst cutting hair.

“How’s it going young squirt?” he enquired, throwing his voice to the corner of the salon.

I backed Tiffin Bell, won 5-2,” I boasted.

“Then you can afford a hair cut he replied,” still in the high squeaky voice.

“Sit in the end chair.”

Ten minutes later I re-entered the betting room sporting a well-slicked head.

“Aprolon won at 7-4 Michael,” Alice said, coughing manfully, adding, “it must be your lucky day.”

“And Harry’s,” I said.

“What are you doing in the big one?” she enquired.

“Well, I’ve got to stick to Wragg now, but c-c-can I have a sub on my winnings? I did have a shilling left over, but I had my hair cut.”

“Ask Taffy to settle up on one of your slips.”

“Bloody hell boyo,” said Taffy, “its like looking for a needle in a haystack. Tell you what, I’ll lend you two bob until Monday.”

“Super,” I replied, and instantly returned the coin to his hand.

“Put it on Las Vegas in the N-November Handicap,” I stammered.

Two fifteen approached and the request for prices from the ticker-tape had the ring of an auction. Five to one Dornot – Rae Johnson; 100-8 Star of Autumn – Charlie Smirke; 20-1 Las Vegas – Harry Wragg.

Arriving just in time for the big race, I recognised the voices of Uncle Arthur (Craven A), and Uncle Henry (Rothmans), through the blue haze. At this time, it was thought expedient by a health fanatic, to take the drastic step of opening a window an inch or two, as visibility had fallen to one pace, and it was difficult to hear the odds over the coughing.

Standing on a chair, Taffy shouted out, “Under orders Manchester,” shortly followed by, “Off Manchester 2-20.”

A stillness now came over the assembly, and strangely, the absence of a running commentary in no way diminished the excitement, as each man prepared himself for the instant finality of the result.

The silence was finally broken by the sound of the ticker-tape. Taffy crouched over it assisting its passage like a midwife at a birth.

“Here it comes,” Taffy warned … “Manchester – 2.15 – first, Las Vegas

20-1, second, Delville Wood 33-1, third, Star of Autumn….”

At this point, Charlie burst in shouting, “Quiet everybody, quiet, I’ve just seen two coppers hanging about outside – there’s going to be a raid – everyone upstairs, quick as you can.”

Charlie then went into his raid-drill, “Alice get rid of the ash-trays, Taffy give me the cash and the books, and put the ticker-tape under the stairs, NOW!”

A crocodile of disgruntled men climbed the stairs to temporarily pay their respects to Alice’s bewildered mother, Violet. Meanwhile, Charlie beckoned to me, “You come with me boy.”

“They’re at the back door Charlie,” Alice cried out.

“Hold them up for as long as you can,” he replied, then staring close into the faces of two bemused customers, said, “You’ve seen nothing, OK – and your haircuts are on the house.”

“Michael, put the plank across the arms of that chair, and sit up on it.” I obeyed instinctively. Charlie then put the books, cash and betting slips into a pillowcase, pushed it under the plank and threw a large white cape around me to cover everything.

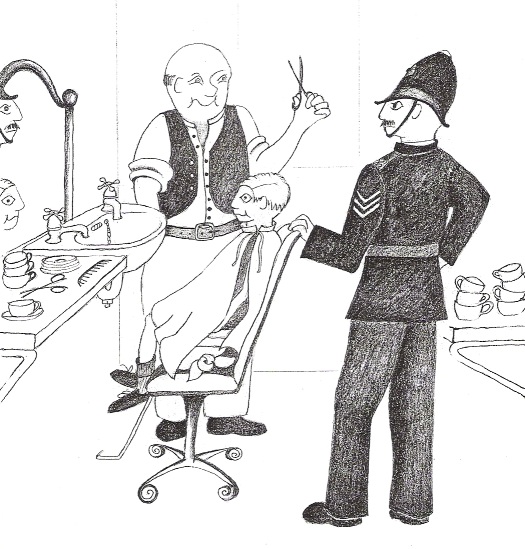

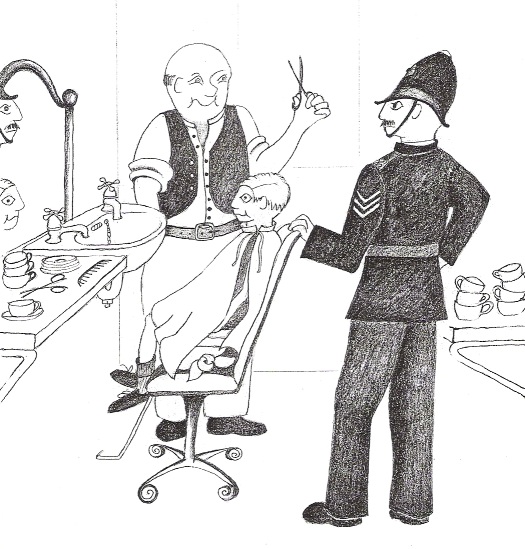

“Afternoon Mr Young.” The stentorian voice preceded the presence of two uniformed police officers.

“Afternoon Mr Young.” The stentorian voice preceded the presence of two uniformed police officers.

“You’ve been very busy this afternoon.”

“Yes, usual Saturday afternoon you know,” Charlie replied, looking a little pale.

“Alice looks as if she has been washing up cups for an army,” the sergeant added sarcastically.

“Customers like a cup of tea with their haircut you know.”

“Yes of course, we must try that approach down at the station,” he retorted.

“Given up the betting, have you Charlie?” he persisted.

“Yes, a mug’s game really you know officer.”

“You’d be a mug if you got caught Charlie – a heavy fine could close your business down.”

“Yes officer, but all that’s in the past now,” said Charlie, riding his luck.

The sergeant’s gaze turned to the customers.

“Been waiting long, gents?” he probed, but their nervous mutterings revealed nothing.

Looking in the facing mirror, I watched the copper circle my chair. I could feel my heart beating – my winnings were in that pillowcase.

“This boy’s nearly done. Perhaps as a favour you could cut my hair next.”

“Crikey,” I thought, feeling a rush of blood to my head.

Suddenly, I blurted out,

“Ch-Charlie’s got to wash it first, officer, I’ve only just got here.”

Charlie’s blenched face sprang to life.

“Yes, course I have. His Mum hates all that Brylcreem plastered all over it.”

I felt myself propelled forward to the basin for a vigorous hair washing. This having been done under the sergeant’s steady gaze, Charlie was then obliged to begin my second haircut of the afternoon. As the sergeant’s puzzled frown deepened, Charlie explained helpfully, “His mum likes it short!”

“Oh well, must be getting along, I suppose.” The sergeant slowly moved towards the door before pausing.

“There’s just one thing you might like to help with Charlie,” he said thoughtfully.

“Of course officer, anything,” said Charlie obsequiously.

“I’ve got ten tickets left for the Police Dance next Saturday, would you like to take them off my hands? Be good for you and Alice to get out occasionally.”

Charlie gritted his teeth and paid up.

Leaving by the front door the two policemen were joined by Uncles Arthur and Henry tiptoeing down the stairs from the now profoundly bewildered Violet.

“What are you two up to – leaving the scene of the crime?” questioned the sergeant.

“No officer,” said Arthur, “we’ve just been estimating for a wallpapering job.”

“A cover up job, more likely.”

As the story of this raid went around Woking, so I became the boy hero, albeit with the shortest haircut in Surrey.

This short story is taken from Ripping Gambling Yarns,

of which Michael has a few signed copies for sale.

Illustrations by Julia Jacs

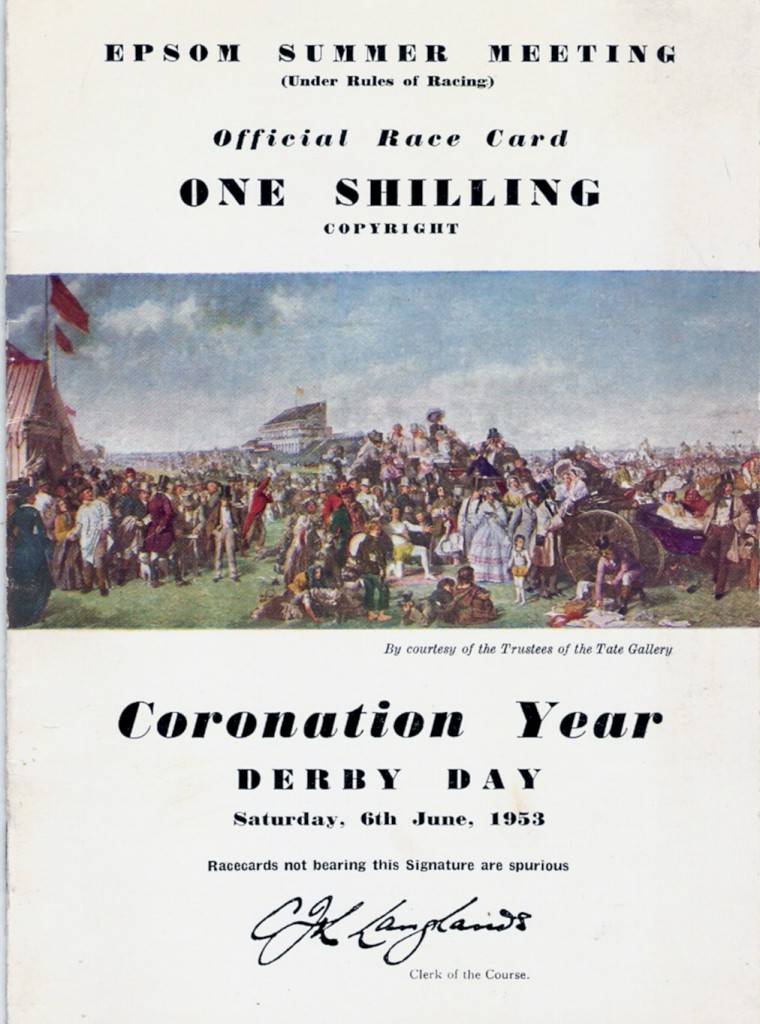

The weather, cold and blustery for the Queen’s arrival, changed suddenly to sunshine in time for the Derby.

The weather, cold and blustery for the Queen’s arrival, changed suddenly to sunshine in time for the Derby.

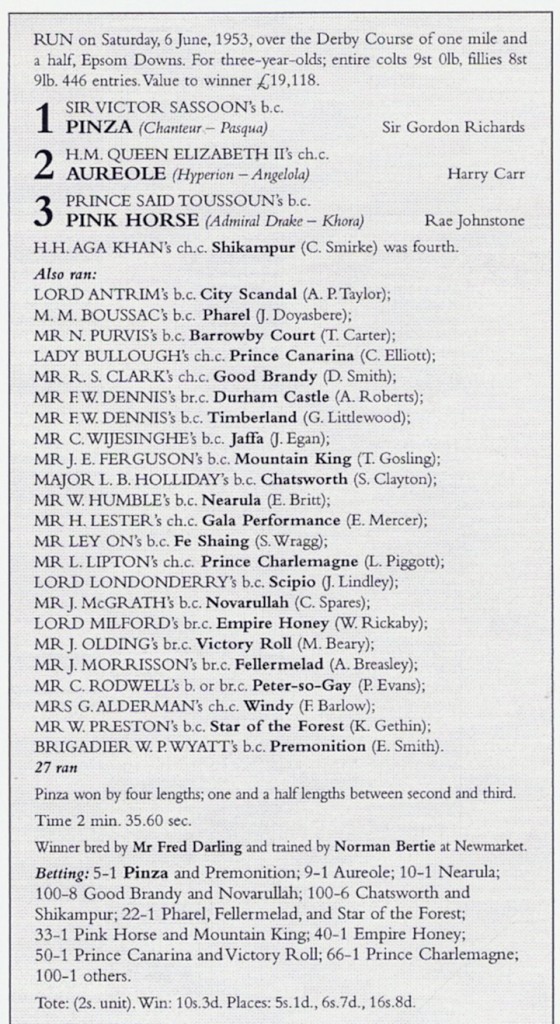

Derby Day was hot and sunny and the crowd, reported to be more than half-a-million, had been swelled by the thousands who had come to London for the Coronation earlier in the week. The Queen’s runner Aureole, having won the Lingfield Derby Trial, had been a leading fancy for some weeks, but after sweating up in the preliminaries drifted out to 9-1. Joint-favourites at 5-1 were Pinza and Aureole’s stable companion Premonition, winner of the Great Northern Stakes at York. Also in contention was the Two Thousand Guineas winner Nearula, who had missed a vital week of preparation and was now offered at 10-1.

Derby Day was hot and sunny and the crowd, reported to be more than half-a-million, had been swelled by the thousands who had come to London for the Coronation earlier in the week. The Queen’s runner Aureole, having won the Lingfield Derby Trial, had been a leading fancy for some weeks, but after sweating up in the preliminaries drifted out to 9-1. Joint-favourites at 5-1 were Pinza and Aureole’s stable companion Premonition, winner of the Great Northern Stakes at York. Also in contention was the Two Thousand Guineas winner Nearula, who had missed a vital week of preparation and was now offered at 10-1.

“Afternoon Mr Young.” The stentorian voice preceded the presence of two uniformed police officers.

“Afternoon Mr Young.” The stentorian voice preceded the presence of two uniformed police officers.