Wild Woolley at White City

“Have you seen the new greyhound paper out this week Charlie – the Greyhound Express? All dogs it is, except for the back page, and that’s horses. You get this, you don’t need another paper!”

Roy and Charlie boarded the fast train at Woking – first stop London Waterloo. They were bound for White City; it was Greyhound Derby Final night, the year, 1932.

Had you been on their Central Line underground train you might have guesed anyway; hundreds of young men, and a few women, strap hanging, swaying, and more than a few reading the new paper. White City had become the Mecca of this fascinating sport and tonight, an unbelievable crowd of 80,000 people would push through the turnstiles to see a race that would go down in history.

Even so, the reason for Charlie and Roy’s attendance, and they insisted on this when they told me some 20 years later, was to back a white dog in a red jacket earlier on the card – or as Charlie put it, a red dog of a different colour.

The greyhound was known to them as Jack, or sometimes Jack o’Lantern when appearing on the London flapping tracks, but more of that later.

Spilling out from the tube station, they were swept along the road towards the track, like the course of a river.

Charlie, a bricklayer and one of the nine Church brothers, had been a fan of the dogs for almost three years, taking in the exploits of the legendary Mick the Miller. Meantime, Charlie’s pal Roy, was a bookies-runner, who would call every day at the Church’s home in West Street, to pick up and pay out bets; number 45 being one of the ‘safer houses’, during the years in which illegal betting flourished.

Forging their way down the street, they were constantly approached by men selling out of suitcases – watches, clothing, tin foods, quite apart from the tipsters and programme sellers. Nearing the stadium, one van, driven off the road, near one of the entrances, was selling a pile of white boxes. Charlie, being inquisitive, pushed in to see.

“They’re shoes Roy. All leather, hand-made shoes, Oxford style, fallen off the back of a lorry in the West End, only this morning!”

Roy came to look. They were selling fast, that’s for sure. And Roy said he could do with a posh pair of shoes for when he went racing. They weren’t cheap, unless they were the real thing that was.

Like almost everything Roy did, it was a gamble and he took it.

“Have you got two pairs of size nine’s there?” he asked the spiv, remembering generously that Charlie took the same size. A well-worn camel-coat dived into the back of the van.

“Two nine’s coming up Gov. Two quid each, OK.”

“Two quid,” recoiled Roy, that’s a bit steep.”

“A bit steep,” the spiv objected. “You won’t see the likes of these for two quid anywhere else – they’re a steal!”

And so they were.

Roy and Charlie joined the long queues to the turnstiles with shoeboxes underarm. People had been arriving at the track from the middle of the afternoon, many with their own food and drink, enough to last them the evening. For such were the crowds inside the stadium, that in order to get a meat pie and a cup of tea, you would run the risk of missing a race and not getting a bet on.

Eventually, after waiting more than half an hour, Roy and Charlie got inside the stadium.

At this point, I think it best that Charlie tells you the story as he told me.

“Inside White City, it looked more like a Cup Final than a dog meeting; the size of the crowd was staggering. Quite apart from all the pushing and shoving, there were long lines to get to the Tote windows, and large clusters of punters hovering in front of the 200 or so bookmakers spread round the track. There was also a military band on the go: ‘Pack up your Troubles, Tipperary’, and that sort of thing, although most of us were too busy, either studying the form, or trying to get a bet on, to take much notice.

“You see, Roy had been given this strong tip from his governor that ‘Jack o’Lantern’, shall we call him, would be on a going night and, we should get on, bundles if we could.

“We decided that a tenner each was the best we could muster (a monster bet for a working man at the time), and when the time came, we positioned ourselves within striking distance of the boards of O’Hara and Billy Broadbent.

“During the parade we kept a careful eye on Jack, his powerful white frame contrasting with the red jacket under the glare of the lights. Then, just before they went in the traps we made our move. O’Hara laid me, £55 to £10, while seconds later, Broadbent laid Roy £50 to £10.

“We were on and the hare was running.”

Uncle Charlie recalled the race as if it was happening in front of him.

“The favourite was in the five box and he got a flyer; two lengths up before the bend. Jack, as we knew, was often slowly away and so he was tonight. But it looked as if he had a bit of trackcraft, and going into the second bend he kept on the rails, moving up to third down the back straight. Around the final bend, he still had a length to make up on the favourite, but he kept gaining, and hugging the rails he went by to win by a neck.”

“I’m sweating now just thinking about it,” Charlie said, as he reached in his top pocket for a handkerchief.

“Tell Michael about the shoeboxes,” interrupted Roy, enjoying the telling as much as Charlie.

“Oh yeah, the shoeboxes, but first came the track announcement over the Tannoy. Apparently, gangs of pickpockets were at work in the crowds, lifting wallets and watches. Then Roy came up with this bright idea,” Roy beamed, as Charlie continued.

“We would go to the lavatory and empty our wallets into the toes of the shoes in the boxes; all except for two fivers – one to celebrate with and the other for emergencies. We reckoned if we were going to get turned over, or hit on the head going home, the last thing they would rob us for was a pair of shoes.”

“Anyway, after about seven races our feet were beginning to give us gyp, so back to the lavs, to switch the cash into our old shoes and try on the new ones.

Now I know what you are thinking Michael, but you’d be wrong, they fitted like gloves, real toff’s shoes they were.”

“And that was another shrewd move,” interrupted Roy, “You see, no-one would be interested in robbing us for two scruffy pair of shoes.”

However, by now, even to this 16-year-old, Roy and Charlie were becoming a tad obsessive.

“Tell us about the Derby,” I pressed, pouring both our visitors another bottle of Bass each. Charlie took a drink, wiped his lips and continued.

“Oh yes, I must tell you that before the dogs came out for the final, they paraded four previous Derby winners, including the great Mick the Miller – he got a fantastic cheer from the crowd. It made you feel as if you were part of history. But back to the race. From the bookies boards it looked like a two-dog race: 8-13 Future Cutlet (trap5); 5-2 Wild Woolley (trap 6), and 10-1 bar. Both dogs had won their semis, but in a first round heat Future Cutlet had beaten Woolley fair and square, to set a new track record.

However, despite all the excitement, neither Roy nor I, wanted to have a bet – you see we had already made our money for the night and there didn’t seem any sense in opening the shoeboxes again.”

Mum and dad started to laugh, visualising Charlie and Roy opening their shoeboxes in front of the bookies!

Charlie pressed on, hardly breaking stride.

“With all the noise going on – I guess you could call it the Derby roar – neither of the favourites broke well. However, Future Cutlet soon took off and crossing to the rails forced Woolley wide. Along the back straight, it was as we expected, a two-dog race, with Woolley chasing hard. Neck and neck into the third bend, Woolley had regained the rails and, when the improving Cutlet ran wide at the last – some said the driver had slowed the hare – Woolley pressed his advantage to win by a diminishing neck. The distance between second and third was 10 lengths and the time, 29.72, was a record for the 525-yard final.”

Charlie’s impressive account brought Dad to say that he should challenge Lesley Welch (the memory man), on the radio.

Suddenly, Charlie looked a bit embarrassed. “Have you got another Bass there Dorothy,” he said to Mum, offering his glass.

Roy, taking advantage of the lull, then said, “Shall I tell ‘em about the presentation of the trophy, Charlie?”

“Oh yeah, go on, Dorothy will like that.”

“Well, Charlie and I worked our way along to the area where we could see the ceremony. Lady Chatham, a good-looking woman, presented an impressive trophy to the owner, Sam Johnson of Manchester. Apparently, he had only paid 25 guineas for the dog. Imagine that, Charlie and I had won four times that amount on Jack. Also, I must tell you, that Wild Woolley, a dark brindle, by the way, had the special 1932 Derby winner’s jacket put on, before they paraded him around the track.”

With Charlie, having run out of steam, it was Roy, who revealed their nightmare journey home.

“After a couple more drinks in the stadium, we joined the 500-yard queue at White City underground station and then, onto the overcrowded platforms at Tottenham Court Road. Eventually, to cap it all, when we got to Waterloo, a Guard told us that there was a Sunday service in operation.”

At this point, Charlie, having downed the Bass, continued the story.

“I remember saying something like, ‘Oh bugger this, let’s have another drink and then get a cab – all the way to Woking.’”

“However, I don’t remember much of the journey, apart from us singing, with the cabbie joining in, friendly like. It had been a great night, so we tipped him handsomely and waved goodbye.”

“A minute later, as we staggered through the front door, it hit us simultaneously – the shoeboxes, the bloody shoeboxes!!

All that money and we’d left it in the bloody cab.

We were desolate – neither of us slept that night. We had no receipt for the fare, we hadn’t taken the cab number, I mean, why would we?”

Charlie continued, “On Monday, the pain grew worse when our pals asked us if we’d had a good time at White City. And Roy’s boss, who had given him the tip, was gobsmacked at our stupidity. Ain’t that right Roy?”

Roy cut in for the finale.

“But miraculously, there was a happy ending. The following Friday, Jane, (dad’s Mum), opened the front door to a grinning taxi driver who handed her our two white shoeboxes. The cabbie told Jane, ‘I dropped a fare here last Saturday night; two blokes who couldn’t stop singing; I reckon anyone who carries such scruffy old shoes around with them must really need them. So here they are. And thank them again for the fat tip.’”

“That evening,” Roy concluded, “Mrs Stebbings, our neighbour, said she heard Charlie shouting and laughing from as far as four doors away. ‘It’s amazing, just amazing,’ he kept shouting – ‘Taxi driver, I love you.’”

Looking back, Charlie’s story went some way to explaining a phenomenon that had always puzzled me.

Why Charlie, although a heavy bettor, but in every other way a reluctant spender, was such a generous tipper?

Footnote: Trained by Jimmy Rimmer, Wild Woolley went on to run in the Greyhound Derby a further three times. In the 1933 final, he finished third to his old rival, Future Cutlet and in 1934, he finished third again, this time to Davesland. Finally, in 1935, now five years old, he was eliminated in the first round heats and subsequently, retired to stud.

This short story is from Michael’s book Black Horse – Red Dog ,

of which he has a few signed copies for sale.

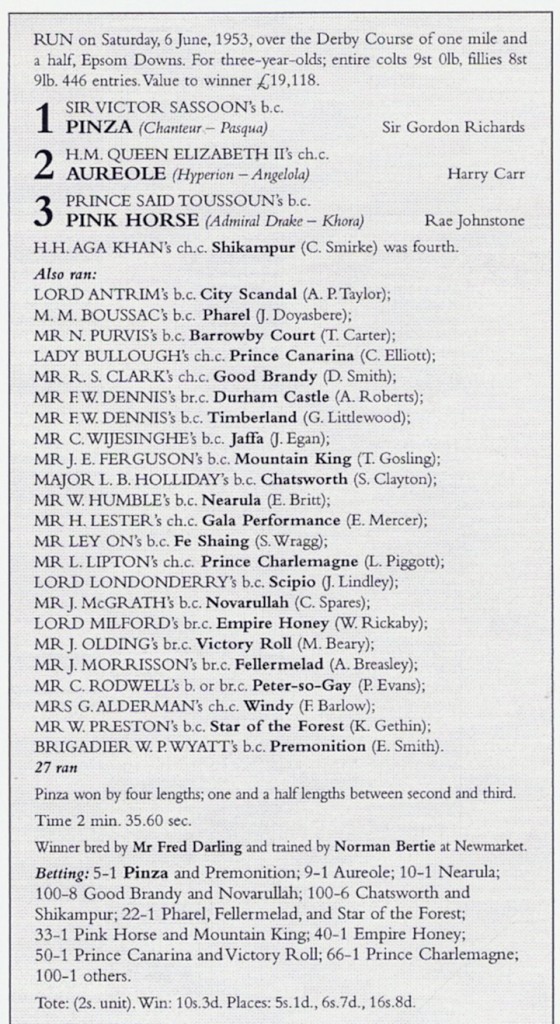

Derby Day was hot and sunny and the crowd, reported to be more than half-a-million, had been swelled by the thousands who had come to London for the Coronation earlier in the week. The Queen’s runner Aureole, having won the Lingfield Derby Trial, had been a leading fancy for some weeks, but after sweating up in the preliminaries drifted out to 9-1. Joint-favourites at 5-1 were Pinza and Aureole’s stable companion Premonition, winner of the Great Northern Stakes at York. Also in contention was the Two Thousand Guineas winner Nearula, who had missed a vital week of preparation and was now offered at 10-1.

Derby Day was hot and sunny and the crowd, reported to be more than half-a-million, had been swelled by the thousands who had come to London for the Coronation earlier in the week. The Queen’s runner Aureole, having won the Lingfield Derby Trial, had been a leading fancy for some weeks, but after sweating up in the preliminaries drifted out to 9-1. Joint-favourites at 5-1 were Pinza and Aureole’s stable companion Premonition, winner of the Great Northern Stakes at York. Also in contention was the Two Thousand Guineas winner Nearula, who had missed a vital week of preparation and was now offered at 10-1.